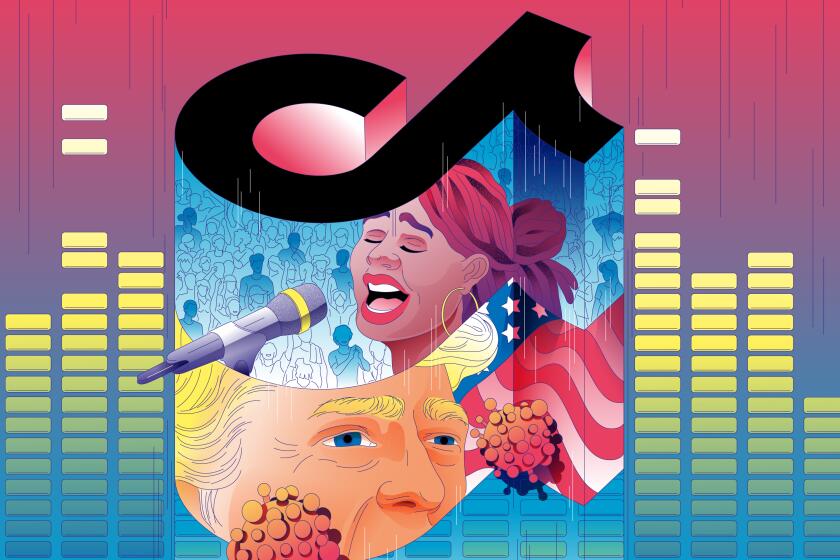

When Prince got ‘Black for real’: The radical ambition of ‘Sign O’ the Times’

Prince needed only a few minutes to paint an indelible picture of the moment when he opened his landmark 1987 album, “Sign O’ the Times,” with a haunting title track about AIDS, crack and Ronald Reagan.

Put another way, the song takes up a deadly disease, a national drug-addiction crisis and a president resented by many for prioritizing economic gain over human well-being.

Sound familiar?

Reissued Friday in a lavish deluxe edition packed with 63 previously unreleased tracks from Prince’s storied vault as well as a live concert video recorded in 1987 at Paisley Park, “Sign O’ the Times” feels startlingly current 33 years later, both in its themes and in the synthed-up funk of tracks like “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” and “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” in which you can hear the ground being laid for the likes of Frank Ocean and SZA.

Yet the album also occupies an important position in Prince’s historical timeline, amid the breakup of his backing band, the Revolution (with whom he’d made “1999” and the world-conquering “Purple Rain”), the end of his engagement to Susannah Melvoin and the beginning of his epic, years-long battle with the record industry. Prince, who died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl on April 21, 2016, initially conceived “Sign O’ the Times” as a sprawling three-disc set but was forced by his label, Warner Bros., to trim it to 16 songs.

To discuss the album’s impact and legacy, I gathered three Prince experts: Daphne Brooks, an author and Yale University professor who wrote liner notes for the reissue; Naima Cochrane, who writes about music and the record industry for Billboard and Vibe; and Michaelangelo Matos, whose book “Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year” is due out in December.

“Sign O’ the Times” is routinely described as Prince’s masterpiece. Is it?

Naima Cochrane: Even if it’s not my favorite Prince album, I think it’s the Prince-iest. It’s the best illustration of his ability to grow, change and adapt his sound and experiment without ever not sounding like him.

Michaelangelo Matos: Listening to the box, it’s fascinating how all the material really does dovetail, even the really old stuff. To find out that “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man,” with almost exactly the same lyric [as heard in an early recording], was from 1979 and yet fits like a glove on this more mature album — he knew his own strengths so well.

Daphne Brooks: When I was working on the liner notes for the reissue, I was going back through reviews from around the time of the release. And Kurt Loder’s review in Rolling Stone was really compelling to me. He was saying, “Prince is doing all the things we know he can do as a virtuoso, but this is an album in which I’m struggling to figure out what the statement is.” In classic rock criticism, there’s always got to be a meaning, but I found myself going back to this record thinking about that question too, and there are ways that Prince delivered his message in an earlier era that hit more powerfully for me. “Dirty Mind” and “Controversy” together — I think of those two records as one — stand out to me as being the most revolutionary.

Fall may not bring starlit shows at the Hollywood Bowl, but it does offer enough great new music to fill your playlists through the end of this miserable year.

Yet by titling “Sign” the way he did, he’s baiting us into thinking of this one as the grand proclamation.

Brooks: It’s a bit of a Trojan horse. We know Black music itself is a statement of life and resistance and being. But in Prince’s case he’s not necessarily engaging with some of the more legible forms of the protest-music tradition. He’s veering away from the expectations of what critical commentary is supposed to sound like to re-center Black sensuality and intimacy and put that in conversation with the Challenger crash and the AIDS epidemic. It’s an album about survival in the face of annihilation.

Cochrane: What I find interesting is that it sounds like it came out years later than it did. It definitely doesn’t sound like it’s just three years after “Purple Rain.”

Matos: It’s like he matured 10 years in those three. It’s exactly the same sort of progression you saw from the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to “Sgt. Pepper” or from Marvin Gaye’s “In the Groove” to “What’s Going On.”

What’s your favorite song on the original record?

Cochrane: “Adore,” all day every day.

Brooks: “Dorothy Parker.”

Matos: “If I Was Your Girlfriend.”

Any of the stuff from the vault impress you? There’s a remix of “Strange Relationship” by Shep Pettibone that I love.

Matos: I think that remix is pretty amazing. It would work anytime, but that’s also the bridge between the album and the rest of the era. And it didn’t come out! If it had, I think it would’ve changed the narrative about Prince a little bit. It would’ve been less about Prince feeling out of time than being right in there.

Pettibone was known for his work with Madonna. Here his presence made me think about how Prince, unlike the other pop superstars of the ’80s, was largely working without a crucial producer figure — a Quincy Jones or a Jon Landau.

Matos: I’ll push back on that — he had Wendy and Lisa [of the Revolution]. They were that figure for him for about four years. “Strange Relationship” is their arrangement — his bones, but they worked on top of it. There were other things like that.

Cochrane: But did he ever really acknowledge that?

Matos: There’s a cover story in Rolling Stone from 1986 where they’re on the cover with him. He pushed them into the spotlight in a way that was good for him, because he didn’t have to do the interview. And they were good at it — funny and irreverent. And he trusted them. The reason he expanded so much musically in this period is that he was taking in stuff from them.

Brooks: We should really hold on to that. To have as close aesthetic interlocutors and collaborators two queer women who are in a relationship with one another — it’s one of the other major markers of how he stands apart from Madonna and Bruce Springsteen and Whitney Houston.

Cochrane: Talking about Wendy and Lisa doing his interviews reminds me that, for those of us who grew up in that original Prince era, when Prince actually started talking on camera in the ’90s, it was like, “What is happening?” I never got used to Prince just being at basketball games and at the BET Awards. And “Sign O’ the Times” was the beginning of that demystification. He was taking in musical influences from other people; he was expanding. This was when we stopped thinking of Prince as this elusive, sprightly, magical artist. All of a sudden he was a person.

As much as they were involved, Prince’s partnership with Wendy and Lisa was fraying as he worked. Do you hear that in the music?

Brooks: You can in the title track, in terms of its atmospheric solitude. It’s really just Prince and a disconcerting, stripped-down beat that in some ways harkens back to “When Doves Cry” but is also completely defamiliarizing.

Cochrane: I remember the song being played on urban radio, and listening to it now in 2020, that’s surprising to me. The structure of it is very jarring. It’s not melodic at all.

It clearly invokes hip-hop. Did listeners at the time perceive any desperation on Prince’s part?

Cochrane: If you’re talking about the reception of Black consumers and Black radio, Prince was never expected to follow any formula. So no matter what he did — even if it aligned with whatever the sound was in some way — I never remember anyone saying, “Oh, Prince is trying to get on the blah-blah-blah.” Prince did whatever Prince was gonna do.

Brooks: Because of his deep historical knowledge and engagement with P-Funk and James Brown and classic R&B and funk, it meant he was legible to a hip-hop public that was listening to all the samples.

Matos: Also, as gear changes and the ’80s progress, his sound changes along with it. He’s starting to experiment with samplers at the same time that hip-hop is coming around, even if he’s not using them in exactly the same way.

Shaken by the death of his friend Nipsey Hussle, run-ins with the police and the Black Lives Matter protests, YG returns with his darkest album yet.

Who else enjoyed that level of creative freedom from their audience?

Cochrane: David Bowie?

Brooks: Bowie had doubled down on form for “Let’s Dance” but then pulled out again with “Blue Jean.” He’d already peaked in terms of pop, but he sort of settled back into a level of experimentalism that everyone expected of him.

Cochrane: That segment of time, starting in ’87 and ending around ’92 or ’93, from the urban standpoint, it’s one of the most transformative eras in music. The sound shifts completely, from quiet storm to full hip-hop dominance and New Jack Swing. Artists get younger. Radio starts splitting formats between main and adult. The whole picture of R&B and urban and soul, it just shifts in a six-year span of time. And everybody ain’t make it out, you know? It was kind of shaky.

What do we know about how Prince came to view “Sign O’ the Times” later in his life? Did he make peace with the fact that it was shortened?

Cochrane: His archivist, Michael Howe, was in agreement that Warner pushing him to drill it down was the right move. The relationship with Warner broke down immediately after, but Michael made the point that this was an example of when he and the label worked well together.

Matos: My sense is that over time it became more of an issue. In 1987 he wasn’t bumming out that he had to strip his album down. But as time went on and things got less and less harmonious between him and the execs, that became a sticking point for him. But you can’t blame the label. He’d been selling fewer and fewer albums every time.

Do you think he’d have been in a stronger position to release the album as he wanted if it had come directly after “Purple Rain”?

Matos: “Around the World in a Day” was released nine months after “Purple Rain.” Not a year — nine months. They would’ve put out anything he wanted at that point.

Even as edited, “Sign” is Prince’s most imposing album. It’s long, ambitious, emotionally complicated. How do you think about its accessibility to people encountering it now?

Cochrane: A friend of mine teaches a class at Stanford about funk and technology, and what I discovered when I went to visit is that because Prince withheld his songs from streaming, the youngest millennials and Gen Z, they’re really excavating Prince in whole now that the music is available.

Brooks: As a college professor trying to convey who Prince was to students, the two places I see them going is to his nonconforming gender politics, which resonate so deeply with this generation, and to his BLM activism, which they were getting around his song “Baltimore” and Freddie Gray. But when they go back into the trove and see these images of “slave” scrawled on his face, they’re like, “This is our person.” And I think of “Sign” as an anticipatory marker of that radicalism.

Cochrane: It’s when he started talking about his Blackness, and the pop world wasn’t ready for that. They knew he wasn’t white. But he was a pop star, one of the biggest in the world. And I think his deliberate revisitation of straight-up R&B — the music world in general was like, “Oh, OK, Prince is Black for real.”

You can’t ignore the fact that the album closes with “Adore,” its most classically minded soul ballad.

Brooks: It’s full circle, right? We have the famous line Prince says when he signs to Warner Bros.: “Don’t make me a Black artist.” But what was always implicit in that was: You don’t get to define my Blackness. “Sign O’ the Times” was saying, “This is all Blackness.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.