Emitt Rhodes, a one-man 1970s cult band from Hawthorne, dies at 70

Emitt Rhodes, the pioneering 1970s one-man power-pop band who retreated into self-imposed silence before resurfacing 43 years later with a star-studded album, died Sunday in his sleep. His death was announced by his friend and producer Chris Price. Rhodes was 70.

The singer-songwriter was far from a household name, but his three early-’70s solo albums, a mix of Harry Nilsson-style innocence and Paul McCartney-esque homespun introspection, are coveted by those who prize post-Beatles pop music. He was neither a troubadour nor a rocker but a kid from the Los Angeles suburbs with an innate sense for songwriting and the technical knowledge to get it all done himself. Riding the technological cusp, Rhodes recorded all of his albums from home, an early proponent of the DIY aesthetic.

Amid the hundreds of tract homes in Hawthorne, Emitt Rhodes’ parents’ two-bedroom house is just another relic of 1950s suburbia, one of many unspectacular rectangular lots that have been personalized by generations of restless tenants. Rhodes’ unique addition was a garage recording studio initially funded by an advance from Dunhill Records in 1969. In exchange, Rhodes was to churn out two albums per year. From 1970 to 1973, he released three, but his failure to adhere to his label’s demand for more product resulted in a four-decade break between his third and fourth albums.

Rhodes was born in Decatur, Ill., on Feb. 25, 1950. His family packed up for Hawthorne when he was 5, his father one of thousands lured to the West Coast by the aerospace industry. By the time Rhodes entered Hawthorne High School (alma mater of the Beach Boys’ Wilson brothers, Redd Kross’ McDonald brothers and Tyler, the Creator), he was gigging regularly in and around the Sunset Strip.

Rhodes’ initial breakthrough was as the drummer for the Palace Guard, a straightforward, seven-piece garage band that was a mainstay of the mid-1960s L.A. miniskirt and go-go boot circuit. He eventually joined the short-lived Merry-Go-Round as vocalist and guitarist, sparing himself the task of dragging his drum set from the South Bay to Hollywood every weekend.

They’ve removed ‘Dixie’ from their name and are set to release their first album in 14 years, one that might be the best of the Chicks’ tumultuous career.

Clad in ruffles and velour, the Merry-Go-Round encapsulated a West Coast perspective on the British Invasion. Songs from their self-titled 1967 debut like “You’re a Very Lovely Woman” and “Live” are three-minute slices of twangy guitar rock and tight harmonies but with a mellower approach than most of the manic, amphetamine-fueled Britons competing for airplay. Both tunes charted in the Billboard Hot 100 but it wasn’t enough to keep the band going. By the end of the decade, Rhodes quit, leaving both the Merry-Go-Round and the Palace Guard to be memorialized on Lenny Kaye’s exhaustive psychedelic rock compilation “Nuggets.”

To fulfill the Merry-Go-Round’s recording contract to A&M, the label released an album titled “American Dream” featuring a set of Rhodes’ solo performances amplified by Hollywood session musicians. Rhodes disapproved of the release and was allowed little input in the process.

Rhodes signed as a solo artist with Dunhill Records in 1969 and spent the next nine months holed up in his garage. Rhodes recorded every instrument with exacting precision — a feat of self-sufficiency that would be his professional downfall. Rather than try to communicate his vision to a band and a producer, Rhodes wore all the hats and the result was a painstaking process. It would have been meaningless if the songs hadn’t been so good.

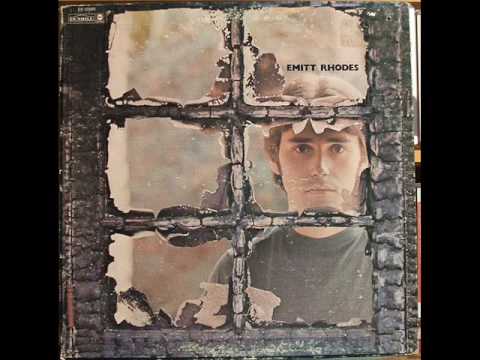

Fifty years ago, Rhodes’ self-titled album was released. He recorded more than half a dozen instruments on every track and a chorus of vocal overdubs. Off-kilter piano-driven tunes like “With My Face on the Floor” and “Fresh as a Daisy” were radio-friendly pop gems that failed to catch on with the general public. His reluctance to tour, coupled with the demands of the studio, only helped to keep him in obscurity. He followed his debut with “Mirror” (1971) and “Farewell to Paradise” (1973), each album more intricately crafted than the last.

Rhodes was burned out by the expectations. Rather than let the quality of his work diminish in order to meet deadlines, he locked up the studio and let the lawyers sort out who was owed what. There were numerous attempts at releasing new songs, but the fickleness of the music industry coupled with Rhodes’ apprehension led to an interminable drought between releases.

In 2001, his song “Lullaby” appeared on the soundtrack of Wes Anderson’s film “The Royal Tenenbaums,” nestled between Bob Dylan and the Clash. The exposure helped introduce him to a new generation of pop fanatics including songsmiths Mac DeMarco and Sufjan Stevens, at a time when his albums were out of print and nearly forgotten.

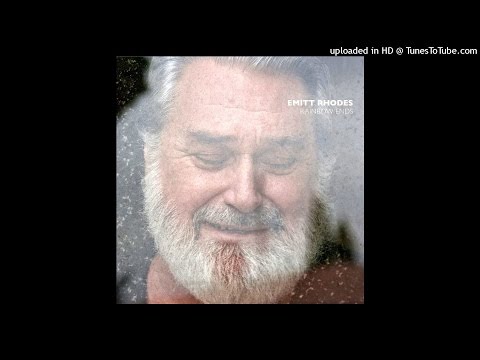

Producer Chris Price was 23 years old in 2007 when he was asked by a friend to check in on the reclusive Rhodes, a man he idolized but had never met. The two bonded quickly but rarely discussed music. One day, after half a decade of friendship, Rhodes revealed a collection of songs he had written. “I showed up at his house and he had all these manila envelopes laid out in his room,” recalls Price. “Each had a song title with multiple revisions of lyrics and sometimes a demo tape.”

Price convinced Rhodes to record them in the garage with the help from a few guest musicians. The resulting album, 2016’s “Rainbow Ends,” was a mature mix of songwriting that stands with his original trilogy of albums. Wilco guitarist Nels Cline and studio wiz Jon Brion contributed guitar solos; Susanna Hoffs and Aimee Mann provided backing vocals. It would be Rhodes’ last musical statement. After the album’s release, he scrapped all planned public performances including an appearance at South by Southwest. He was proud of his work but unwilling to travel too far from home, a creature of habit and a victim of his own debilitating insecurity.

Rhodes never left the California suburbs. He relinquished the spotlight to his shaggier contemporaries in the canyons and lived fairly anonymously in the same house for 65 years. “He was ahead of everybody,” says Price. “He could take what was around him and make it great and something that you couldn’t distinguish from a big studio production. He was a great songwriter and singer but more than anything, what he has contributed to recording culture is invaluable.”

Rhodes is survived by his two sons, Forrest and Ethan, and a daughter, Thea.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.