L.A. boasts one of world’s most vibrant salsa scenes. The coronavirus may wipe it out

Until recently, Colombian percussionist and bandleader Clodomiro Montes made a decent living doing what he loves best: playing a soulful repertoire of Afro-Caribbean hits at restaurants and nightclubs in the Los Angeles area. A timbales player with dazzling technical chops and a keen understanding of salsa swing, Montes performs with his wife, Karina Zurita, a singer who also plays hand percussion and guitar.

Montes moved to L.A. in 2005 after gaining experience in the tropical music scene of his native Cartagena, then as a touring musician in Asia. Now at 42, he finds himself out of work for the first time in his life — quarantining in his rental apartment in Glendora with his wife and their two children.

“It’s a waiting game,” he says in Spanish laced by a melodious Colombian accent. “I consider myself lucky because I’ve always been disciplined about money, but our savings are dwindling. We have frozen all payments on phone service and credit cards. We’re down to paying rent and buying food, counting the days for things to get back to normal.”

The question is: Will there ever be a back to normal?

Perhaps more than any other musical genre, the local salsa scene has been thrown into turmoil by the pandemic.

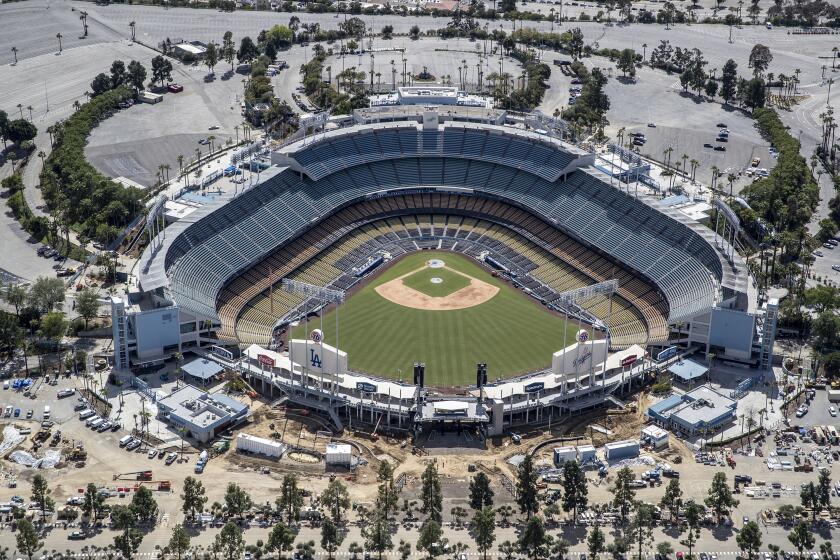

Historically, L.A. has always boasted a rich and varied circuit devoted to tropical music genres like salsa, bachata, merengue and cumbia. At venues throughout the city — from the Hollywood hangout El Floridita to downtown’s flashy Conga Room at L.A. Live to the retro charm of the Granada in Alhambra — dancing in close intimacy with a variety of partners is an integral part of the experience. Add a tiny stage filled to the brim with 15 sweaty musicians jamming together, and you realize live salsa is the antithesis of social distancing.

“It’s such an unsafe environment. You can’t play a saxophone while wearing a mask, can you?,” says Dena Burroughs, whose website vidasalsera.com has chronicled the local salsa scene since 2005. “In the context of a pandemic, a salsa club is like a messy mondongo soup — your sweat, hands, hair and other body parts are in constant contact with other people’s.”

The music known as salsa — a fusion of Afro-Caribbean dance formats with jazz, R&B and subtle echoes of rock — developed in Cuba and Puerto Rico thanks to the efforts of visionary bandleaders such as Beny Moré and Rafael Cortijo. It flourished in the ’60s and became a global phenomenon during the ’70s in New York when the Fania label brought together stars like Héctor Lavoe, Willie Colón, Tito Puente, Celia Cruz, Ray Barretto and Rubén Blades.

As an epicenter of the film and music industries, Los Angeles attracted a growing number of Afro-Caribbean musicians. By the ’90s, the city boasted one of the richest salsa scenes in the world, with players from all over Latin America and a variety of offerings — from traditional Cuban charanga to trombone-heavy conjuntos and virtuoso Latin jazz ensembles.

In the U.S., contemporary artists like Marc Anthony, Víctor Manuelle and Gilberto Santa Rosa still command big audiences of all ages, even though salsa has lost considerable market share to bachata, reggaeton and a new wave of intriguing urban-pop hybrids. Still, the local scene attracted thousands of devoted fans and dancers before the pandemic started.

Now, everyone from musicians and DJs to dance instructors and club owners is attempting to process the shock — alternating between feelings of acceptance, hope and the inevitable predictions of doom.

“It’s impossible not to consider the worst-case scenario,” says Brad Gluckstein, founder and majority owner of the Conga Room and the man who single-handedly changed the way concerts of Afro-Caribbean music are experienced in our city. In the late ’90s, the original Conga Room location at Miracle Mile allowed fans to enjoy performances by genre legends — from Celia Cruz to members of the Buena Vista Social Club — in the intimacy of a Latin-styled ballroom complete with polished wooden floors and an eccentric MC from Panama.

“It would be heartbreaking for me personally,” he says. In recent weeks, Gluckstein laid off all his employees, save for his general manager. “I always thought of the Conga Room as the Troubadour of Latin music. If that legacy ceased to exist, it would be beyond disappointing. This is a lifelong project for me and my family.”

“Everyone seems to be taking it differently,” adds Montes. “I’m friends with an older singer who’s probably one of the most talented artists to come out of Colombia. But he depends solely on gigs for his livelihood, and in fact rents a room from the bandleader who employs him. He doesn’t have a plan B, and it pains me to see him falling into depression.”

Montes himself is proving to be particularly resourceful. The son of a professional musician, he grew up enamored with the Colombian brand of salsa pioneered by artists such as Joe Arroyo, Grupo Niche and Orquesta Guayacán — marked by fast tempos, impossibly tight arrangements and a nostalgic, almost melancholy approach to melodic lines. Montes’ move to the U.S. was sponsored by a fellow Colombian and highly respected veteran of the L.A. scene, Yari Moré. Once Montes established himself, he founded his own band — Colombia Latin Soul — while also joining an electronica trio, Palenke Soultribe, a gig which includes frequent European tours.

“I imagine there will be lots of work once this is over, but I wonder if the orchestras will remain untouched,” he reflects. “In the salsa world, everyone’s looking to save their own skin. Musicians may despair and sell their services for less. They may not be as loyal to their original groups as one would hope.”

The indie-rock band Sure Sure share a house, so during quarantine, it’s performing for fans over six consecutive nights, each show from a different room.

“We’re in a total limbo,” agrees singer Chino Espinoza, leader of a formidable orchestra, Chino Espinoza y Los Dueños Del Son, that has been playing together since 2003. “This is not going to change in three or four months. I doubt people will have the confidence to go out again and brush against each other the way you do at a salsa club. We will need to reinvent ourselves. A total reset is needed.”

“I would not want to reopen without live music,” adds Earl Miller, owner of the Granada. “Salsa fans are a loyal community, and they like the authentic experience of a real orchestra. Right now, we’re relying on state and federal government to assist us. As long as they do their part, we can survive being closed for three or four months. But they have to put their money where their mouth is.” The salsa scene may need to quickly adapt new practices.

“I see the clubs morphing into restaurants with live entertainment, the way it is in Cuba,” says Burroughs. “Go, listen to the band, dance with your wife sort of thing. The time of social mingling is over for a while.”

“We have a rabid, dedicated fan base,” adds the Conga Room’s Gluckstein. “I think the crowds will eventually come back. They miss our venue and the authentic energy that we create. Once the funding from [the] Payroll Protection [Program] comes through, I’m hopeful we can rehire our employees.”

“I think most clubs will probably close their doors by the time it’s all said and done,” predicts Espinoza. “Some will remain open simply because their owners don’t care about making a profit. Much of the salsa scene is kept alive by people who have invested their hearts in it.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti has told top city staffers that Los Angeles might prohibit big gatherings until 2021 because of the coronavirus threat.

As he spends his days in seclusion laying down tracks for a new album, Montes seems to mirror the same passion — his career fueled by a deep commitment to the music.

“As a bandleader, I’m particularly worried about getting back on my feet as soon as possible,” he says. “I want to be able to hire and support all the musicians who have stood with me for so many years.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.