Elton John may be on his farewell tour, but he still has a lot left to say

VANCOUVER, Canada — Here’s Elton John on his day off, in a sleek, modern house by the water somewhere in Vancouver, sitting at a kitchen-adjacent table with a book of crossword puzzles, dressed like — well, like Elton John on his day off. Iridescent black Gucci tracksuit, white moon-boot sneakers adorned with crystal-studded belts that gently jingle-jangle as he moves. They turn out to be Gucci FlashTreks that retail for $1,590. The belts are removable, should you wish to entirely defeat the purpose of paying $1,590 for gemstone-accented sneakers.

John, 72, has been living here with his family while playing a run of shows around Canada. Tonight he and husband David Furnish, 56, and their two sons will fly home to Los Angeles. Right now Furnish has taken the kids to Dairy Queen and the house is tranquil. Outside the afternoon sun glints off the rain puddles on the patio and the wings of distant seaplanes descending silently into Departure Bay. Soon a chef named Gaultier will bring around coffees white with foam and sugar-free cookies that look like tiny cakes of birdseed — the finest birdseed, the kind you’d feed an ungainly beautiful bird that might be the last of its kind on the planet.

“I like to move forward,” Elton is saying. “I’m not nostalgic. I don’t dwell. I’m not interested.”

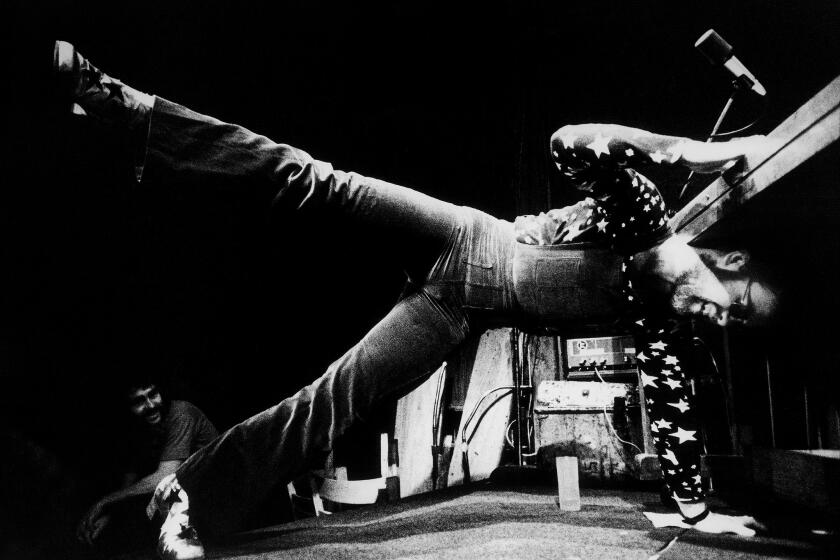

When Elton John flew to Los Angeles to make his U.S. debut at the Troubadour on Aug. 25, 1970, the prospect of a visit to America was so tantalizing to his British pals that many accompanied him.

Whatever impulse compels other rock stars to dig through the vaults, to unearth alternate takes, to retrospectivize — he doesn’t have it, he says. He’d always rather make something new. And yet he’s spent the last year or so taking his estimable legacy out for a global victory lap. On his Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour, which began last September, he’s playing epic, three-hour greatest-hits shows. The film “Rocketman” — part fanciful jukebox musical, part superhero origin story, with Taron Edgerton as a young Captain Fantastic battling toward self-acceptance — hit theaters in May. Now there’s a book — “Me,” John’s first-ever autobiography, in which sheltered, fearful middle-class Reggie Dwight rechristens himself Elton Hercules John, blazes a cocaine-fueled vapor trail across the ’70s and ’80s, and somehow winds up a loving husband, a doting father and a man more or less at peace, surprising everyone, including John himself.

“Four summers ago in France, where we have a house, David sat me down and said” — and here he stops, annoyed. On the other side of the kitchen island, a few of John’s associates are conferring in hushed tones that are not hushed enough for Elton John’s liking. In a weary, imperious voice, he says, “Can you not talk, please?”

The word talk rings like a Champagne bottle exploding on a dressing-room wall, and this momentary flash of the old, infamously tantrum-prone Elton is all it takes. Everybody in the room who is not Elton John pipes down immediately.

Anyway. As he was saying.

“David sat me down, and said, ‘Ten years ago, you always said you wanted to die onstage. That was the way you were going to go. We were just going to travel around being two very lucky gay people. Circumstances have somewhat changed. Now we have two children. I’m going to write a five-year plan — what do you want to do?’”

John was 68 then. He’d been touring the world since the late ’60s. What he wanted, he realized, was to reorganize his life, with Furnish and the kids at its center. They began planning one more tour — an Elton John tour to end all tours, a kind of Viking funeral for some of the biggest pop songs of the 20th century. He has no plans to stop recording or performing live, but if you want to see him play outside Britain or the United States after this, you’ll have to book him privately — $3.4 million is his rumored quote. He likes the idea of doing a residency somewhere, maybe the Hammersmith Apollo in London, but he’d play only newer stuff, from albums like 2013’s “The Diving Board” — consummate late-period works that have languished in the shadow of his crowded back catalog until now.

“I can’t go back onstage and sing ‘The Bitch Is Back’ and ‘Crocodile Rock,’” he says emphatically. “That’s over. When this tour finishes, wherever it finishes ... I am not singing those songs again. You can stick them up your bum. They’re great songs, but I have so many other songs I’d rather sing.”

On the Farewell tour, though, he’s singing “The Bitch Is Back,” and “Crocodile Rock,” and “Tiny Dancer,” on a mammoth stage adorned with images commemorating key moments from a vast and varied career — Gucci’s logo and “Soul Train’s,” Ryan White’s likeness and Billy Elliot’s. Eventually, during “I’m Still Standing,” Elton’s whole surreal life begins flashing before our eyes on the video screen behind him — a clip-show montage, testifying to just how long Elton has been not just famous but ubiquitous, more like a statesman than a pop star, a kind of ambassador for celebrity culture itself. Here he is with Gianni Versace, with Eminem, with Homer Simpson, with RuPaul and Ed Sheehan and Kermit the Frog and Teri Hatcher and the Country Bears. But of course we’re the most important friends he’s made along the way. “Without you, I’m absolutely nothing,” he told the audience at Anaheim’s Honda Center in September, as he undoubtedly does at every one of these shows, meaning it every time.

And then he plays some more hits, and at the end of each night, he climbs onto a moving platform in the stage floor that carries him up a ramp to the base of the giant screen, and at the top of the ramp a door opens in the screen. Before stepping through it, like a smiling spaceman boarding his saucer, he waves goodbye, and no matter what you may understand intellectually about Elton John’s plans for the future or the inability of rock stars in general to stick to the promise implicit in a “farewell tour,” it’s impossible not to feel a pang, and maybe a child-brain urge to wave back. We will have Elton John around for a while yet, but we’re watching the sun go down on the monoculture in which he or anyone else could accumulate three hours’ worth of instantly recognizable hits.

John had considered writing a book before. He and Interview magazine editor Ingrid Sischy (“my best friend — like my sister”) had talked about putting something together. When Sischy died, in 2015, of breast cancer, John put the idea aside. It was Furnish who suggested he revisit it.

“The children need to read it when they’re older,” John remembers him saying, “and when you’re maybe gone, to know what you were like.”

So John sat for around 60 hours with another friend, journalist Alexis Petridis of the Guardian, telling the story of Elton John in his own words. John says their first conversation was about October 1975, when John came to Los Angeles to play the first rock concert at Dodger Stadium since the Beatles’ penultimate live show nine years earlier.

“Cary Grant was backstage,” John writes in the book, “looking incredibly beautiful. I had gospel singers, James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir, performing with me. I had Billie Jean King come out and sing backing vocals on ‘Philadelphia Freedom.’ I had the security guards dressed in ridiculous lilac one-piece jumpsuits with frills. I had California’s most famous used-car dealer, a man called Cal Worthington, come on with a lion — Christ knows why, but I suppose it all added to the general gaiety.”

That same week, John had released his 10th album, “Rock of the Westies,” received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and attempted suicide by overdose. He survived to rock Chavez Ravine in a sequined Dodgers uniform designed by Bob Mackie.

Deep down he was still “poor Reg,” a nervous English kid from an uptight English household. “I didn’t want for anything,” John says today, “except I was afraid of my own shadow.”

You know much of the rest: He becomes Elton John, who is afraid of nothing and bound by no rules. He meets Bernie Taupin, the lyricist with whom he’ll enjoy an almost telepathic creative bond that continues to this day. Between 1970 and 1975 he releases nine studio LPs, not counting soundtracks and live albums and record-company-reconstituted cash-ins. By the time he gets around to losing his virginity, he’s already a rock star. Those first five years are a whirlwind. A representative sample of his diaries from the period appears in the book: “Woke up, watched Grandstand. Wrote ‘Candle in the Wind.’ Went to London, bought Rolls-Royce. Ringo Starr came for dinner.”

“I have five years of diaries like that,” John says, laughing. “My life was like that every day. Had dinner with David Bowie and Marc Bolan. Went to Cartier. Wrote ‘Yellow Brick Road.’”

He discovers that cocaine helps him overcome his natural reticence in social situations. Then he needs alcohol to take the edge off the cocaine, and marijuana to take the edge off that. He burns the next 16 years that way. What begins as a kiss-and-tell memoir about being sexually sheltered becomes a frank account of indulgence. John finds he’s able to achieve physical sexual arousal even when gacked to the gills, but in his social circle he is pretty much alone in this regard. Out of necessity, he begins staging and observing erotic scenes between others.

“I was more of a voyeur than I was a sexual participant, most times,” he says, “and I think that saved my life in the ’80s, without question — being a gay man at that time.”

He comes out in the pages of Rolling Stone in the ’70s. He gets married to a woman — recording engineer Renate Blauel — in 1984. Things get messier and messier. At one wild party, he spots a gardener mingling with the guests and attempts to throw him out, at which time the man turns out to be a shabbily attired Bob Dylan. Eventually, there is drug treatment, and regret, and letters from rehab in which Elton curses cocaine for all it took from him.

It’s a rueful book but also a colorful one, full of priceless detail from a jet-set existence (Versace, we’re told, “thought Miuccia Prada was a communist, because she had designed a handbag made from nylon”) and the kind of wisdom God grants only to madmen who’ve crossed the water and lived to tell. The moral of an Elton story about pranking Iggy Pop, John writes: “If you’re planning to run onstage in a gorilla suit and surprise someone, always check first to see whether or not the person you’re surprising has taken so much acid before the show that they’re unable to differentiate between a man in a gorilla costume and an actual gorilla.”

Eventually our hero finds true love, with Furnish, then a successful London advertising executive, who shows him what it’s like to be with an equal partner for the very first time. Before that, John says, “It was always 80/20 — I was the boss. People lived with me for, like, three or four months. They got a Versace wardrobe, a Cartier watch, and then after four months they hated my guts, ’cause I took all their freedom away from them. I did that so many times, and I didn’t realize what I was doing, until I got sober. I didn’t let people be who they were. They were my property. It’s terrible. I was Mr. Picket Fence — I’m gonna live with you for the rest of my life, but you’re living with me on my terms and not yours.”

John survives the AIDS crisis and lives to be a kind of designated mourner for his community, and he performs the same service for his country after his friend Princess Diana dies in a 1997 car wreck, pursued by paparazzi. He sits at the piano in Westminster Abbey and sings “Candle in the Wind 1997,” his elegy for Marilyn Monroe, with lyrics rewritten by Taupin in Diana’s memory.

In this moment England needs Elton John to be everything Elton John is — it needs his genius and his humanity and his fearlessness about pure sentiment, his emotive courage. He becomes a channeler for a nation’s grief. In the book, he admits it made him uncomfortable when his funeral song, released as a charity single, ended up topping sales charts around the world, and that it was a relief to move on to less emotionally loaded projects, such as recording a John/Taupin original about Wendy Testaburger for an episode of “South Park.”

Then comes civil partnership, and two sons — by surrogate, in 2010 and 2013 — and a brush with death by prostate cancer, a story that culminates, in Elton’s telling, with Sir Elton Hercules John, Commander of the British Empire, losing control of his bladder onstage at Caesars Palace. These indignities resolved, the book ends more or less where we came in — with Elton in his 60s, loved and loving, deciding to wind things down.

He’s as excited as ever about music. He’s nostalgic for the way he used to work — for the kind of fast, cheap, disciplined record-making he did once he started bringing his touring band into the studio on albums like 1972’s “Honky Chateau.” Cutting three or four tracks a day. He’s curious to see if he can do it like that again. Taupin is writing lyrics for a new record even as we speak, John says. “I said I want the album to sound as big as the Grand Canyon and as empty as the Grand Canyon and as cinematic as the Grand Canyon,” John says. “That’s my brief.”

But the tour is a success, and the itinerary keeps expanding, so he’ll write his part of this record on the road. He’s got over 200 shows left to play. Goodnight Auckland, goodnight Glasgow, goodnight Des Moines. Toward the end of the afternoon, he is asked about that moment in the Farewell shows where he steps through the door in the video screen and into the fourth dimension of his own history. For the audience, it’s catharsis — an acknowledgment that Elton John, among the last pop-cultural constants linking 1969 to 2019, will not be here forever. But what does that bit of symbolically freighted stage business feel like if you’re Elton John? What does he think about, when he climbs on that elevator?

“I don’t like heights,” John says, “so I’m going, Oh, God. There’s a big hole at the bottom of that ramp. If I lost my balance and fell, I would slide down the ramp and go straight through the floor. So I’m grinning and saying goodbye” — he laughs — “and hanging on for dear life.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.