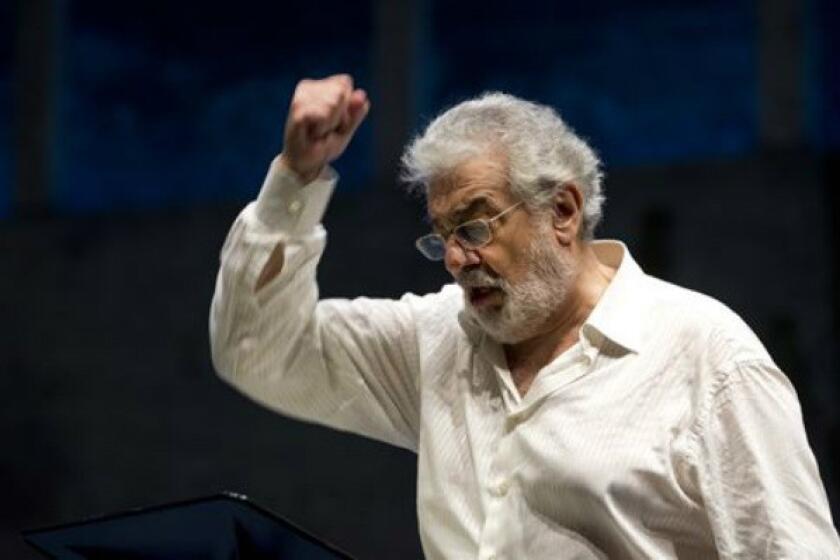

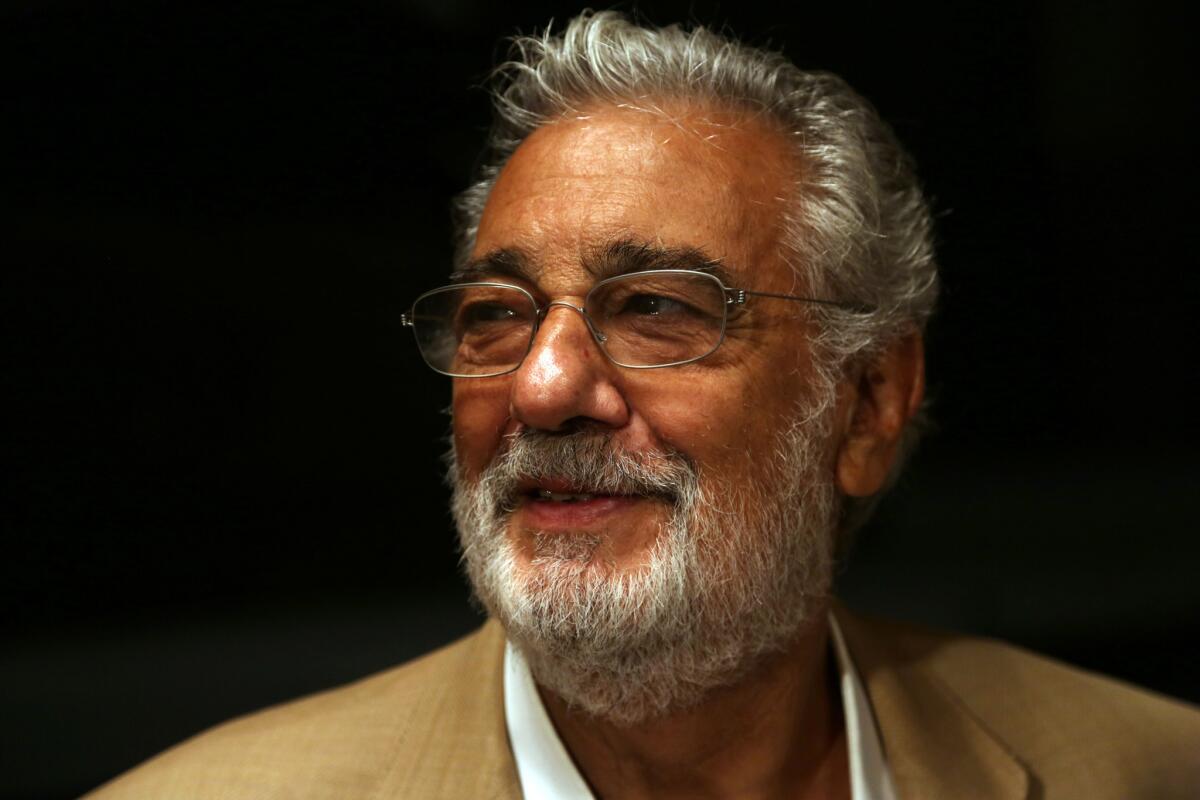

Commentary: Plácido Domingo had to go, but he still matters

Plácido Domingo is a towering figure, but he is not larger than life.

That much became true Wednesday with the news that, amid allegations of sexual harassment, Domingo has resigned as general director of Los Angeles Opera and has withdrawn from all of his scheduled performances here.

The announcement has left his fans, his company, this city all reconciling the troubled present with a revered past deserving of celebration. His has been one of the greatest careers in the history of opera, and his outsize presence in our community has generated substantial good. And this is not to say he is leaving in disgrace. He makes it very clear in his statement that he is being pressured by allegations about his behavior toward women, and he has said the reports are inaccurate.

The L.A. Opera investigation of the accusations continues. What is happening behind the scenes, and you know all kinds of things must be happening behind the scenes, is hard to discern. The lawyers are at their business.

This is the world of opera, and it may be hard to keep high drama, on stage or off, out of any proceedings. In operas, wrongs are either righted, leading to forgiveness and redemption, or they are not, leading to tragedy. In life we prefer laughter to tears, as John Cage liked to say.

In opera that ain’t necessarily so.

In a note Wednesday to L.A. Opera employees, company President and Chief Executive Christopher Koelsch thanked Domingo “for his integral role in the creation of our company and his decades of service … to the Los Angeles creative community as a whole.”

Indeed, the effect that Domingo has had in L.A. has been immeasurable. He was a catalyst in the creation of L.A. Opera. He appeared with the Royal Opera of Covent Garden at the Music Center during the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival, which gave the city a taste for world-class opera at an optimistic and opportune moment.

Plácido Domingo says he will withdraw from future performances and focus his attention on clearing his name after sexual harassment allegations.

However, Domingo’s efforts to bring opera to Southern California go back much further, to 1966. As a last-minute replacement for an indisposed singer in Gounod’s “Faust” — one billed as a Mexican tenor (he was born in Madrid but grew up in Mexico City) — Domingo was the newcomer starring in the first performance of the new San Diego Opera.

The next year came the creation of the Music Center Opera Assn. in L.A. Despite its name, the association saw its job as importing New York City Opera, the company that put Domingo on the opera map. In 1970, City Opera opened its Music Center season with a glittering “Roberto Devereux” starring Domingo and Beverly Sills. (This is the Donizetti opera that Domingo had been scheduled to sing in L.A. this coming February, making his withdrawal from future performances all the more melancholy.)

In no time, star became superstar. Over the next 13 years L.A. had so gotten to know, and demand, Domingo that a Times report in 1983 — he would star in a new Royal Opera production of Puccini’s “Turandot” as a highlight of the next year’s Olympic Arts Festival — was the 400th Times article with his name.

The “Turandot” was a hit just as L.A. began another of its periods of clamoring for its own opera company. The ambition of the Olympic Arts Festival added can-do confidence. Doors opened thanks to the declining sway of Dorothy Buffum Chandler, an opera denier, over the Music Center. And Domingo joined the opera-loving cabal of movers and shakers and donors angling to take charge.

In 1985 The Times published Domingo’s denial of rumors he was moving to L.A. to take over the Opera Assn. The next year, Domingo starred in the opening night of the new Music Center Opera. The review of that “Otello” was the 1,125th Times entry with Domingo’s name in it.

And not all of the attention had been for his singing. Earlier that year he was in the press for his leading role in garnering help for a devastating Mexico City earthquake.

Domingo remained not just involved with, but absolutely integral to, L.A. Opera until Wednesday. He led it for 16 years. He was its identity. He was the face and the voice of opera in L.A. His fame and the size of the Latino population grew together. That meant a lot.

He wasn’t all that concerned with conflicts of interest. He used L.A. Opera as a place to work on conducting. He used the company to develop new roles, especially when age forced him to become a baritone. He started his international Operalia singing competition, which gave him a steady stream of new talent to try out in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. His name goes first on the Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artists Program. He controversially employed his wife, Marta Domingo, to direct opera. Integral, indeed.

He had bad ideas, such as commissioning some pretty awful operas. Deborah Drattell’s inept “Nicholas and Alexandra,” in which Domingo starred as Rasputin, was one. Howard Shore’s hapless “The Fly,” which Domingo conducted, another. But he also put his support behind any number of L.A. Opera pioneering adventures — Achim Freyer’s production of Wagner’s “Ring,” in particular.

Where does this leave us?

This is not the place to try Domingo on the harassment allegations. With luck (though don’t hold your breath), the truth will come out. Did he cross the line? Was he threatening or merely affectionate, which is how many Europeans look at it? Was it a different time, when what we now understand as inappropriate was not then? Was he a product of another culture? Was it a complex mixture of all those things?

Administratively, Domingo obviously crossed all kinds of lines. In none of this was he ever anything close to perfect. Great artists never are. Without their devils there would be no angels. With demand for change coming faster than society knows how to handle it, the calculus to evaluate the balance between good and bad, to know whether the punishment fits the crime, is beyond us.

There is no excuse to be blind to Domingo’s lapses. But that doesn’t give us any excuse to fail to acknowledge what Domingo has meant to us.

He’s been an unstoppable powerhouse, and, in the end, we may very well have to conclude that he’s human, and that maybe he couldn’t have done all the great things he did without also having done what he shouldn’t have, and hurting people along the way. In Domingo’s case, being an unstoppable powerhouse may not allow much time or room for self-reflection.

Hearing him sing in Verdi’s “Luisa Miller” in Salzburg in August was for me a sad spectacle. His voice sounded worn. Fans stamped and bravo-ed their approval to show their love but were just as clearly offering a vocal rebuke to the American #MeToo movement.

I prefer to think back to May and what turned out to have been Domingo’s last appearance with L.A. Opera — and likely his last in the U.S. In Manuel Penella’s zarzuela “El Gato Montés” (The Wild Cat), he took on his 151st new role.

He had gotten his start in this opera as a teenager with his parent’s zarzuela company in Mexico City. Long past being the romantic lead, he was now the ill-fated fugitive trying to reclaim a love of youth to tragic consequences. He was riveting. One-hundred percent believable. A great performance by a great artist that felt like a warning to old lions trying to recover what they’ve lost.

What a way to go.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.