How a master filmmaker channeled Hitchcock with ‘the James Stewart of Korea’

Warning: The following contains spoilers from “Decision to Leave.”

For celebrated South Korean director Park Chan-wook, the process of falling in love resembles a criminal investigation: Both are an attempt to understand the motivations behind another person’s actions.

“Just how a detective needs evidence in order to solve a case, when you’re in love, you also are constantly looking for evidence of whether this person loves you or doesn’t love you,” explained Park, 59, via an interpreter during a recent interview in Los Angeles. “For both the detective and for someone in love, the important thing is to get rid of any prejudices.”

His latest cinematic confection, the amorous mystery “Decision to Leave” (in theaters Friday), follows detective Hae-jun (Park Hae-il) as he probes a man’s seemingly accidental death. The deceased’s wife, Seo-rae (Tang Wei), now a widow from China living in South Korea, cooperates with his inquiry. But soon their interactions go beyond the professional and their mutual attraction muddles the truth.

Famous for the dazzling brutality of his seminal revenge thriller “Old Boy” and the eroticism of his lush lesbian period piece “The Handmaiden,” Park maintains that, whatever the genre, all his movies are tales of love. With “Decision to Leave,” he aimed to imply it — but never outright express it.

“I wanted to make a film telling a love story without saying the words ‘I love you,’” he said.

The mystery genre, Park’s chosen conduit this time around, scratches an existential itch in the human condition, he thinks. Since our lives overflow with enigmas — the meaning of our birth, what comes after death, why the people around us behave as they do — we long for certainty.

“In the mystery genre, the authors give you the answer to the question. Not to your personal questions, but they answer the question that is central to the story, and it’s explained clearly for us,” Park explained. “We’re always hungry for that because our own questions are never quite answered.”

Still, “Decision to Leave” is less a whodunit than a whydunit: Although we learn the identity of the perpetrator, we are not privy to that person’s reasoning. And that’s only one of the ways in which Park subverts or manipulates the tropes of the genre.

Tired of how violent detective characters have become in popular culture, Park conceived Hae-jun as an opportunity to depict a civil servant whose sole mission is to serve the people honorably.

“If you look at classic Hollywood films, the detective characters in those films are very different from those in contemporary media,” Park said. “There wasn’t a lot of violence in those characters. Not just Hollywood films, but films around the world about detectives.”

Park Hae-il and Tang Wei play a homicide detective and a suspect in this luxuriant feast of a thriller from the South Korean director Park Chan-wook (“The Handmaiden,” “Oldboy”).

But the film doesn’t focus solely on the occupational duties of its male protagonist. After all, it’s also a romance. For Park, Hae-jun was the key to create one unified story connecting the investigation process and the process of falling in love.

“There are not two different tracks where one is to investigate the suspect and the other is to meet the woman,” he said “It’s one singular track where both stories are told at the same time. He doesn’t meet the woman in his off time.”

Passion and police work are also intertwined in the subplot that Park features as homage to the works of Martin Beck and Ed McBain. When Hae-jun tries to deescalate a tough situation with a delinquent he has been after, his therapeutic chatter to comfort the criminal doubles as a representation of his feelings toward Seo-rae. And the more Hae-jun enters Seo-rae’s world, the more hints appear pointing us to suspect he might die just like her two husbands.

Despite the challenges of crafting a mystery set in our digital present, in which cellphones and CCTV surveillance cameras have computerized much detective work, Park ultimately decided against making the film a period piece.

“I would’ve preferred to have a nice quality paper with someone writing in beautiful handwriting with their ink pen to each other,” Park noted. “But if the story was told that way, it would not reflect our modern society and would come off as rather forced.”

Instead, the director embraced modernity, devising a new approach to text messaging on screen — a shot of the device with the text in the foreground and the face of the person on the other end of the conversation in the background — that has no exact correspondent in real life.

“When the male character is texting, his eyes are not actually on the phone but are on the woman,” he said. “That is why, despite the use of modern technology, I feel these scenes came off as even more romantic than writing letters in a Victorian-era setting.”

The interplay of two voices is woven into Park’s creative process: Since 2005’s “Lady Vengeance,” he has collaborated with Jung Seo-Kyoung on all of his screenplays. Recruiting her, he says, is one of the best decisions he’s made in his career. Because they sit down to put every single letter on the page together, Park sees their individual contributions to the narrative as nearly indistinguishable.

“I wanted some change to my mostly male-centric works, which is why I needed a female co-writer,” Park recalled. “Femininity is something that is difficult to explain, but you can feel it in the works ever since we started working together as a team.”

Breaking down what should have won the top prizes at cinema’s prestigious festival, from a critic who saw all the eligible films.

Although the pair have traditionally avoided writing with specific casting in mind, as the idea for this seductive murder mystery brewed in their minds, Park asked Jung to imagine actor Park Hae-il as an example of the type of man detective Hae-jun is, even if they didn’t have any concrete intention of giving him the part.

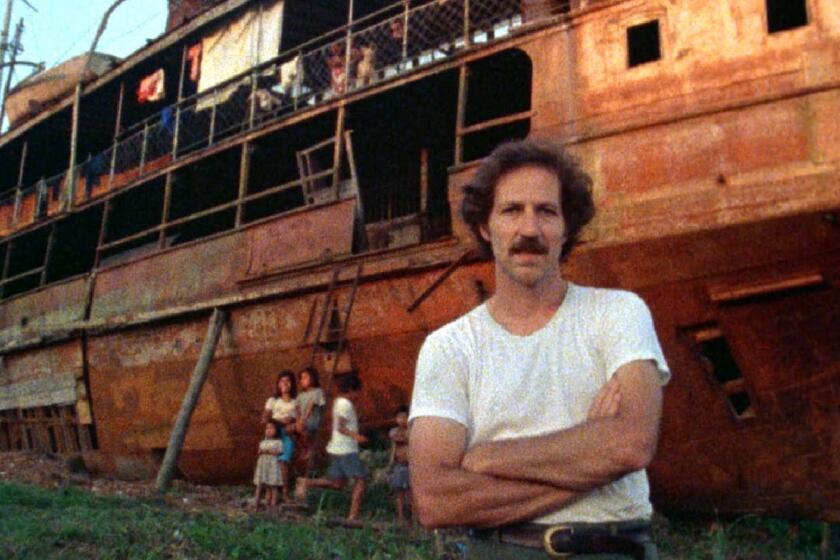

To put it in Hollywood-friendly terms, Park describes Park Hae-il as “the James Stewart of Korea.” Park and Jung also envisioned the character of the widow as a Chinese woman precisely so they could bring on Tang, whom they both had loved since seeing her in Ang Lee’s “Lust, Caution.” Fortunately, both performers signed on for the project early in the development journey.

“For the first time in my filmmaking career, I had my two lead actors cast before I started working on the script,” Park said.

Seo-rae’s background taps into the complex history between China and Korea. It also afforded Park another opportunity to experiment with modern technology in an old-fashioned romance: Although her Korean pronunciation is good enough for native speakers to understand, and her grammar while texting in Korean is perfect, people still notice it isn’t her first language. According to Park, she uses words that a Korean person wouldn’t normally use in the context of the situations she encounters.

Park makes use of this distinct challenge in communication through translation apps. Even if Seo-rae’s Korean is outstanding, whenever she has too much to say or wishes to say it quickly, she says it in Chinese for a translation app to relay her message to Hae-jun. This frustrates him because the tone and emotion of her words is lost in the flat digital voice.

“Both Hae-jun and the audience have to think back to a few moments before and remember the tone and the face she had when she was speaking,” Park said. “They have to pull those images out of their head and combine them with the content of what the app is saying. I believe this is a new way of movie-watching that was not seen in previous films before.”

As “Decision to Leave” has traveled the world since it premiered in May at the Cannes Film Festival, where Park won the best director prize, the seasoned South Korean master has come across writing that compares his sensual mystery to the work of Alfred Hitchcock.

“’Vertigo’ is the film that made me want to become a filmmaker. As someone who didn’t go to film school, Hitchcock was my film school,” Park said. “That influence definitely does exist, but I didn’t think of ‘Vertigo’ when I was writing ‘Decision to Leave.’ Reading the articles by Western critics mentioning that film I did understand where they came from.” (While some viewers might assume that Park lifted Seo-rae’s fear of heights from “Vertigo,” for instance, he confessed he was channeling his own severe aversion to heights.)

In the effort to reinvent the trappings of the cinematic traditions he is borrowing from rather than dispense with them entirely, Park feels he has mostly succeeded — especially how he concludes his characters’ intense and hazardous love affair with Seo-rae’s death.

“This romantic ending where the woman commits suicide because she cannot get the heart of the man is a clichéd element in romance films,” Park said. “But in a way, this ending is also different from traditional romance endings because the suicide in my film is caused by the woman’s desire to forever remain an unresolved case in the man’s life.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.