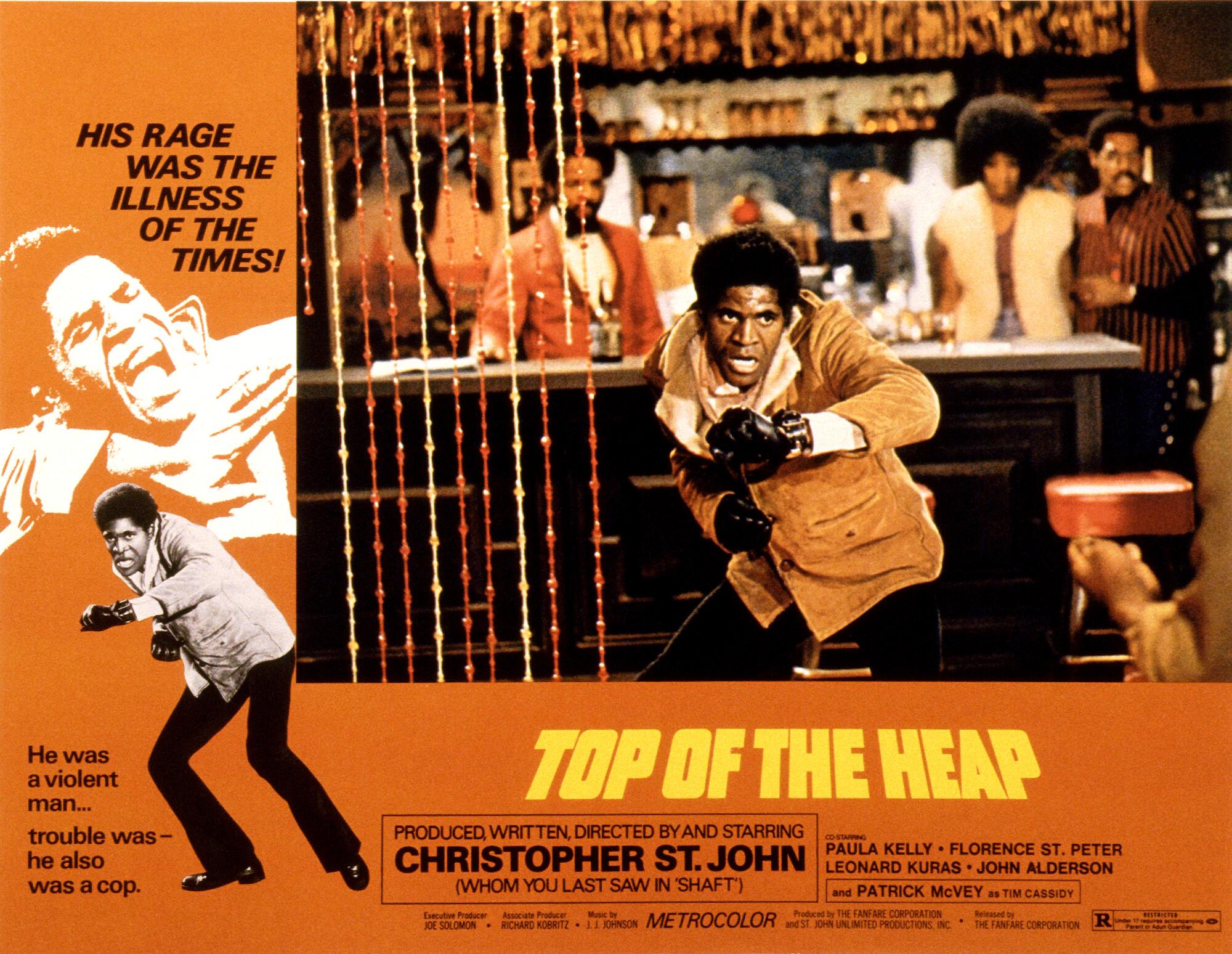

Fifty years ago, Christopher St. John directed “Top of the Heap,” a film about a D.C. police officer named George Lattimer. This was just a year after “Shaft” minted a tough Black detective with style to burn — and St. John in a supporting role as the Black radical leader Ben Buford. St. John also starred in “Top of the Heap” as Lattimer, who is less a crime fighter with a knack for solving cases and catching crooks than a beat cop who’s mostly miserable about his lot in life and daydreams about being the first Black man on the moon.

If you’ve never heard of “Top of the Heap,” there’s nothing quite like its wild, fearless mix of genres and tones: race commentary, Afro-Futurist satire, cop-on-the-beat melodrama and fantasy sequences that start trippy and end with gut-punching grief. The boldness of the film evokes the work of Melvin Van Peebles (“Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song”), who was a contemporary of St. John’s. Yet “Top of the Heap” has remained scarce in film histories and in cinemas.

That’s starting to change. A restored version of “Top of the Heap” had an anniversary revival run at BAM Rose Cinemas in Brooklyn last month, and the film is being featured on the new Blacknuss Network streaming channel. It also can be seen on Shout Factory TV, Tubi, the Black Film Archive and Amazon. In 2020, the New Yorker’s Richard Brody called “Top of the Heap” “a major discovery” and “a crucial work of Afrofuturism.”

The spotlight comes none too soon for St. John, an actor-director who — like so many Black filmmakers before and since — found his artistic road run out all too quickly.

Despite some positive reviews, and a slot at the 1972 Berlin International Film Festival alongside works by Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Top of the Heap” was lumped in with a wave of blaxploitation movies, without attaining the same cult status as “Superfly” or “Across 110th Street.” St. John didn’t direct a second feature, and despite theater work, his roles tapered off as the 1970s went on.

Out to prove that Black film before Spike Lee is not a monolith, Maya Cade’s platform showcases more than 250 movies by Black creators and where to watch them.

Still, after stumbling upon the unusual film, I couldn’t resist tracking down the man behind it — the film’s director, writer, producer and star.

“It’s a fierce kind of movie,” says a genial and chatty St. John, now 82, reached at his home in Cincinnati. “‘Top of the Heap’ didn’t belong with all those movies in the blaxploitation era. But it managed to save itself!”

In conversations on and off since last spring, he reflected on his career’s challenges, wearing his heart on his sleeve. But he kept returning to a downright buoying point of view that with “Top of the Heap” he’d accomplished something special.

‘Power from creating’

St. John remembers playing hooky from school to go to the movies, and looking up to Sidney Poitier, whom he met years later by chance.

“I was a Black kid growing up in Bridgeport, Conn., and I was afraid of everything,” St. John says. “And I didn’t know anything. But my power came from creating something.”

Like hundreds of other aspiring actors, he headed to New York, breaking away from his family of seven siblings, an overworked mother and a father who died young. His path from the stage to “Top of the Heap” in the 1960s and ’70s was not unheard of in the thriving Black theater scene. Van Peebles and Ivan Dixon (“The Spook Who Sat by the Door”), to name just two, also built theater careers in addition to directing feature films.

A chance audition led St. John to an Actors Studio membership and a front-row seat for some of the great talents of the past and future. But the pressure of the theater audition grind took its toll.

“I would pretend I was a tough guy but I would go home and stay there, decompress at night,” says St. John, who had been an accomplished carpenter before pursuing theater. “I remember Bobby De Niro had a book where he would write everything down: what he did, who he saw, what he was doing. I never did that. But maybe I should have!”

Following his own energies, St. John founded a theater in a space he discovered off 42nd Street. At the time he was working for a fabric and rug company, but he built out the space so he and others would have a place to rehearse and workshop productions.

His personal breakthrough came when he landed a role in “No Place to Be Somebody,” Charles Gordone’s provocative Broadway play about an African American bar ownerand a surrounding ensemble of characters. Based on Gordone’s memories of working in a Greenwich Village bar, the play starred Nathan George and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize. St. John, who initially played a supporting part, took on the lead role when George moved on to Hollywood.

“It’s a very tough play. Chuck didn’t mince words. He said things in that play that would just be like a torrential rain!” St. John says. “And it entered my consciousness. Things inside me — what had happened to me, my family, all the Black people I’d ever known — it brought all that stuff up.”

St. John’s training with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, he says, underlined how much he had repressed. “By the time I did ‘Top of the Heap,’ it was all in full bloom.”

“I think the theater background makes all the difference in the world. Christopher worked on organizing people, on the sets. You do as much building as you do directing,” says Floyd Webb, a Chicago film programmer who for a long time chased “Top of the Heap” for Chicago’s Blacklight Film Festival and landed it last year.

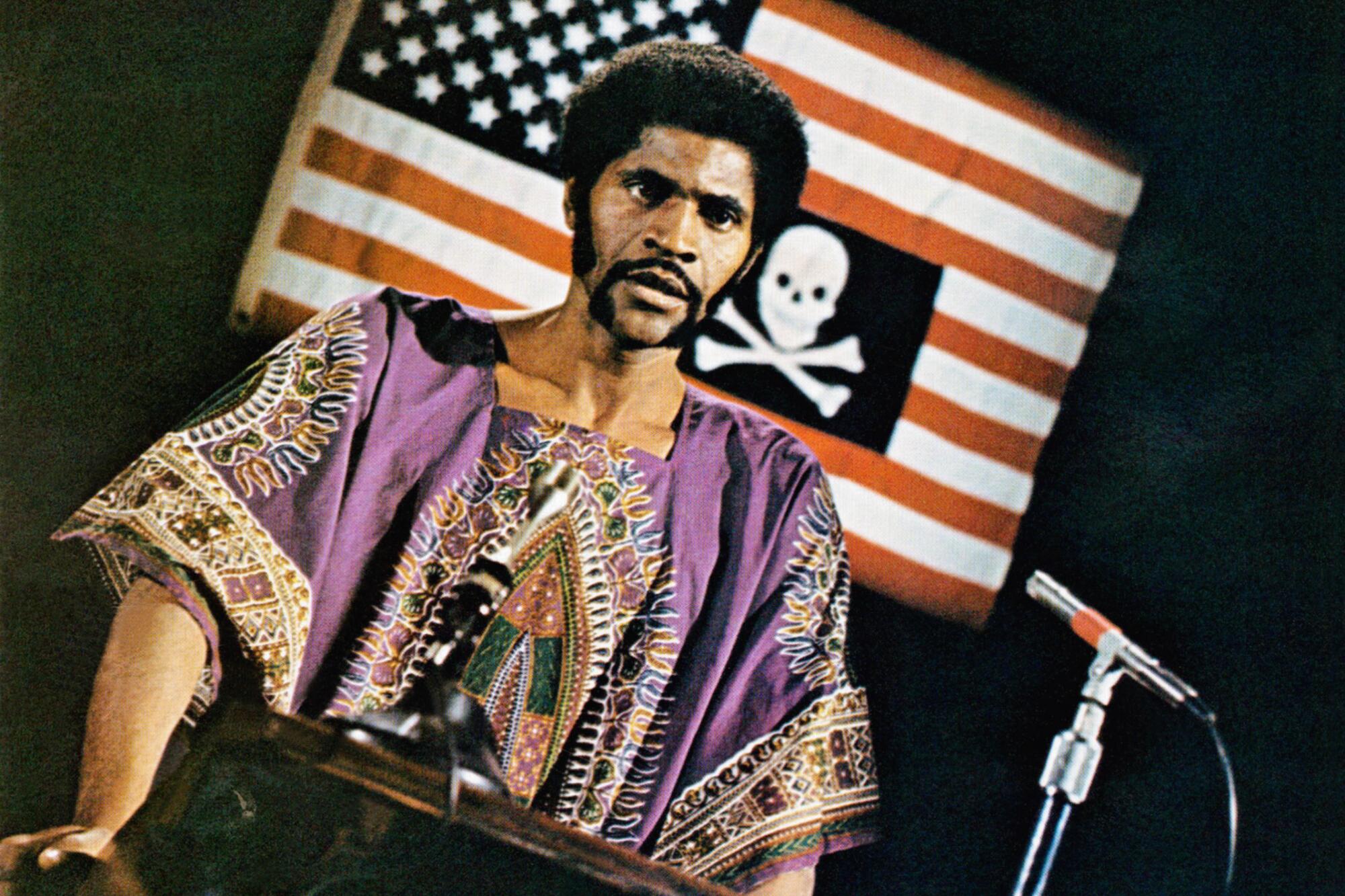

But first came “Shaft,” St. John’s big break as a film actor, for better or worse. As he remembers it, his agent called him to audition for the role of Shaft.

Arriving at the audition, he found he was up for another part, Buford, the Harlem militant who helps Shaft. He walked out.

“Walking home I said to myself, ‘What did you do? Leaving a part in a big Hollywood movie!’” St. John says. But the director, Gordon Parks, called him up and urged him to take the part.

It’s a pivotal role, helping Richard Roundtree’s take-no-prisoners detective track down a gangster’s kidnapped daughter and mount a full-scale assault on a mobbed-up hotel. St. John cuts a striking figure onscreen but he brings a low-key focus to Buford, coming off more as a consternated neighborhood leader than a fiery radical.

St. John wasn’t called back for the “Shaft” sequels but poured all of his creative energies into “Top of the Heap” and its conflicted protagonist.

Radical sadness

“I like your movie, but why don’t you make it about a baseball player?”

That, St. John remembers, was one prospective producer’s response to making “Top of the Heap.” Once again, St. John walked out. He secured another producer, though he knew he was being valued for the dollars-and-cents draw of his “Shaft” association.

Yet if anyone was expecting cash-in blaxploitation, “Top of the Heap” was not it. The movie opens on a dirty lot where a raucous demonstration is in progress. Lattimer is one of several police officers called to break it up. Spattered with mud, Lattimer wonders what he’s even doing there. His first line: “Bulls—.”

What follows isn’t a one-man crackdown on the criminals of Washington, D.C., but a strange drama with an ache, a sadness that feels almost radical.

We see Lattimer passed over for a promotion and getting impatient with his friendly white partner (Leonard Kuras, a friend from the Actors Studio). He’s given room to be a complicated character, at times absent as a husband and father, and seeing a dancer (singer Paula Kelly) on the side. St. John gives him a pent-up frustration, stalking into and out of scenes, a storm brewing that might lead to anger or tears, we can’t tell. He fends off a racist cab driver (Allen Garfield, another New York colleague); near the end, he goes on a car chase that’s frantic and hopeless at once.

George’s refrain in the movie is a kind of declaration of independence: “I can do any goddamn thing I want!” He says it even when, or especially when, his options seem narrow.

“I think that’s a hopeful response to the reality that he faces,” says Mark A. Reid, a professor at the University of Florida and author of “Redefining Black Film.” “I think he’s caught in the middle. ‘Shaft’ is a superhero. This guy is more human. He’s real.”

St. John had two brothers who were cops. One was shot and killed by someone they had grown up with. He remembers putting on his brother’s uniform just to see what it was like. “I just went outside and started walking around,” St. John recalls. “And I noticed how people would relate to me.”

In “Top of the Heap,” Lattimer play-acts in satirical daydreams, imagining himself as the first Black astronaut. He “rehearses” a moon landing in a studio, answers questions at a press conference with wry humor and has a bizarre fantasy with a Swedish nurse. In other words, he does “any goddamn thing” he wants.

Next to this, the film’s domestic dramas can feel a little old-fashioned, but St. John puts these disparate elements together with jump cuts and other editing flourishes. Van Peebles’ work comes to mind, but St. John locates his reasons closer to heart.

“Well, that was my life. It’s not just a straight linear story. It’s about how on an inner level, I was a lonely little boy,” St. John says. “That’s how I got through my life so far.”

Beyond blaxploitation

The climax of “Top of the Heap” remains remarkable among police dramas of the time. George imagines himself going home to Alabama for his mother’s funeral but finding a disappointingly empty town. The scene arouses his rage, then his grief. Instead of a crowd, his mother appears, sitting on a chair in the middle of a dusty street. They commune, the camera circling.

For St. John, a lot of unprocessed emotion over the preceding decade went into that scene.

“I was afraid to go to Alabama myself as a human being because I had read all about the terrible things that had happened,” St. John says, recalling the lingering wounds of the struggles in the civil rights movement. He also remembers traveling through South Carolina and being chased out of a rural gas station at riflepoint.

Shooting this scene with his screen mother (Beatrice Webster) in “Top of the Heap,” he says, “I knelt down and I just started crying real, real, heavy tears.”

The fantasy sequences were apparently too much for the film’s since-deceased producer, Joe Solomon, who ran the exploitation outfit Fanfare Film Productions. St. John remembers a big fight with Solomon just before shooting. The language in Lattimer’s speeches — their heartfelt rage — were toned down, according to St. John. Scenes with his character’s son were cut — which St. John, father of a young son at the time, took to heart.

“He said to me, ‘What the hell kind of movie are you making?’ He was pissed off. Because he was making an exploitation movie,” St. John says, “and I was not.”

The film was released, featuring a score by J.J. Johnson (“Across 110th Street”), but St. John felt shortchanged in his share of the film’s box office. He grew disillusioned after the conflicts with his producer and was exhausted by the experience.

“I remember I had a near breakdown because of that,” St. John says. “This was supposed to be my great movie.”

Yet there were positive notices, and among the film’s fans were two leading lights of Black cinema at the time, Bill Gunn (“Ganja & Hess”) and St. Clair Bourne (“Paul Robeson: Here I Stand”).

More recently, critics have rediscovered the film on DVD or streaming. Reid compares its experimentation to Cinema Novo in Brazil, or to singular independent portraits such as “The Last Black Man in San Francisco.”

St. John continued to act here and there over the years. He remembers auditioning for “Lady Sings the Blues” and “The Last Detail” (“a fine movie!”), and writing a spec script for “Ironside.” He was commissioned to direct a documentary about an Indian cult leader, but the trip was deeply traumatic and the film took years to finish. His son, Kristoff St. John, grew up to be an actor — a star fixture on “The Young and the Restless” — but sadly died at 52 in 2019.

St. John eventually left Los Angeles and receded from show business, though he still works on screenplays and hopes to release his documentary. He seems to be the last man standing, outliving his collaborators on “Top of the Heap” and securing a place in the history of American independent film.

“My inner soul said you kind of do something that you really, really, really believe in,” St. John says. “And that’s how my career went.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.