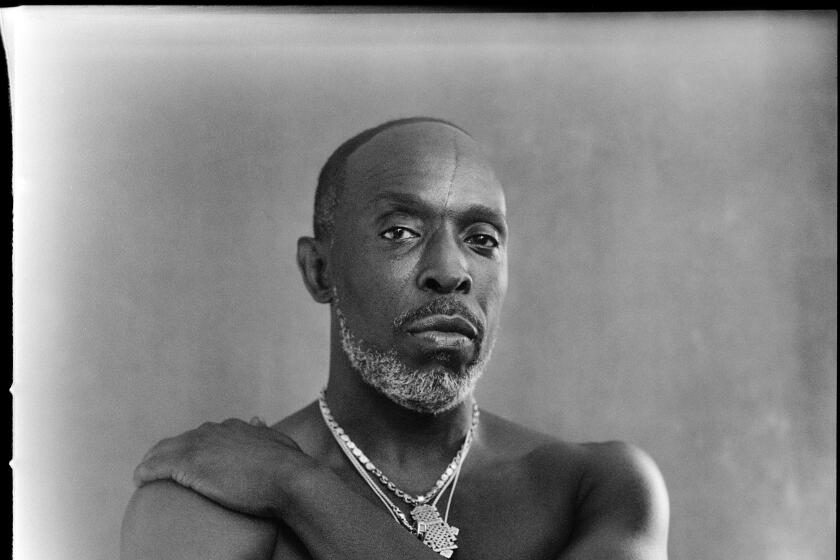

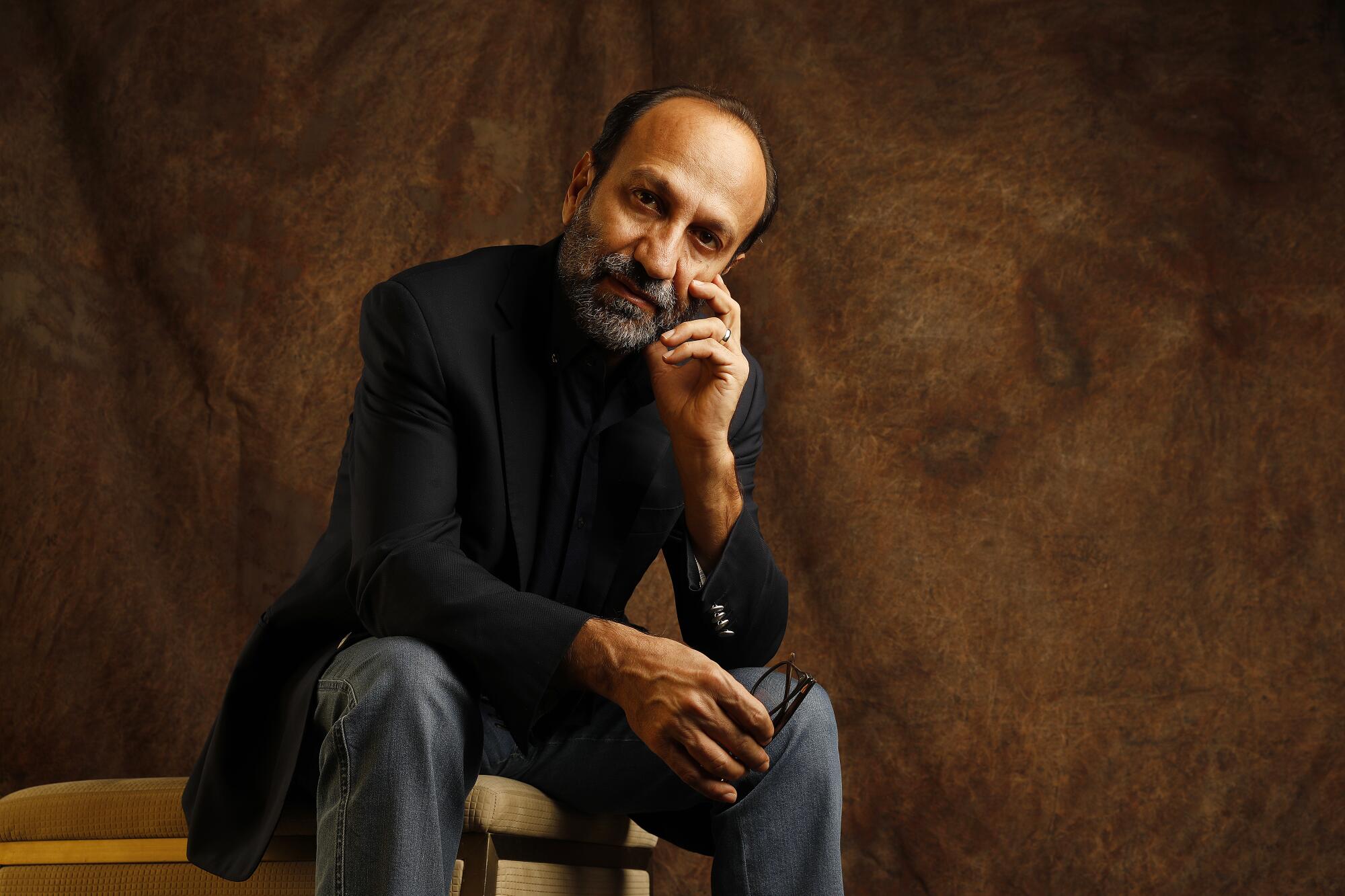

Moral crucibles that upend the lives of everyday people, never above reproach but always deserving of sympathy, are a dramatic propellant for the films of Iranian writer-director Asghar Farhadi. There are no choices with ideal outcomes in his gripping entanglements of quotidian altercations, only blemished characters with conflicting motivations.

At the center of his newest onscreen tribulations in “A Hero” (in theaters now and on Amazon Prime on Jan. 21) stands Rahim (Amir Jadidi), a humble father behind bars for failing to pay his creditor. Given the opportunity to temporarily leave the prison and solve his affairs, he steps into a providential occurrence. Upon finding a woman’s purse with enough gold to so revolve his predicaments, he chooses to return the windfall, instantly turning into a paladin of honesty worthy of public admiration. But the reverie doesn’t last.

Orbiting Rahim’s newly found shimmer are the prison authorities, eager to take credit for the inmate turned media darling; his young son, who’s terrified of a longer separation; a staunch romantic partner with steadfast resolve; and a myriad of other citizens either questioning the integrity of the yarn he’s spun or rooting for the dismissal of his transgressions.

Amir Jadidi plays a man who hatches a desperate scheme in this latest drama from the Oscar-winning director of “A Separation” and “The Salesman.”

Farhadi says that what distinguishes “A Hero” from the rest of his work is that, rather than only probing the fractures of a single family unit, the story makes an entire community ethically liable for the events that transpire.

“When somebody does a good deed, it’s natural for people to want to see that be exalted. But if this repeats continuously, there’s another meaning behind it: Sometimes we make somebody a hero to escape our personal responsibilities and society’s,” Farhadi says, speaking via an interpreter during a recent interview in Los Angeles.

Farhadi can track the roots of his latest marvel of social realist cinema to his days as a young student, when he first saw the play “Life of Galileo” by the German writer Bertolt Brecht, about the Catholic Church’s trial against Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei. The troubling implications of the scientist and philosopher’s perverse indictment at the hands of those who once praised him had rattled around in the filmmaker’s mind for years.

This notion periodically returned to him when seeing reports in newspapers or on television about individuals who’d gained short-lived fame after committing an honorable deed, namely giving back lost property to its owners. While teaching a class on documentary earlier in his career, Farhadi asked his students to record one of those news stories of casual uprightness so they could discuss them.

What most intrigued him about these do-gooders’ overnight stardom was that the general populace and institutions alike demanded that the man or woman of the hour have an exemplary past and be striving for an equally irreproachable future. Deviations from their perceived immaculate rectitude were not tolerated. By making them symbols of virtue, the court of collective discourse tried to deprive them of their inherent proclivity to err.

“We are human beings, and we gain a lot of experience from making mistakes. If all your life you are expected to not make mistakes and be perfect, that’s a very torturous life,” Farhadi explains. “And it’s not that simple to say what is right and what is wrong, what is a mistake or not. Sometimes you do something you believe is correct, but others see it as a negative. Sometimes you have the intention of doing what’s right, but the result is wrong.”

In “A Hero,” Rahim becomes the victim of suffocating expectations imposed on him by those exploiting his precarious position to satisfy their interests. The intent is to conceive a sanitized version of him. “They change his clothes and tell him not to smoke in front of others,” he says. “They only want to see the image of him that they saw in the newspapers.”

As ‘best movie of the year’ prizes pile up, including a shout out from former President Obama, director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi explains ‘Drive My Car.’

When considering the distinct points of view from which the film’s peripheral characters interpret his protagonist’s ordeal, Farhadi thought of the ancient parable “Elephant in the Dark” by foundational Persian poet Rumi — known in Iran as Mowlānā (Farhadi isn’t pleased with the English name given to one of his country’s greatest storytellers).

In the fable, part of his extensive “Masnavi,” multiple people enter a space devoid of light housing a pachyderm. After touching the animal, they each believe it’s a different object. Farhadi references this tale to prove how the same event can produce dissimilar reactions.

But although his fate may seem entirely out his control, since everyone around him has an opinion on how he should behave while in the eye of the storm, Rahim and his agency, Farhadi thinks, shine when it matters most. Freedom, from financial ruin and from jail, would allow him to raise his boy and begin anew with a supportive woman, but the concoction of pity and admiration he receives en masse proves a spiritually costly way out.

“At the very beginning, Rahim seems like a character who doesn’t make any decisions for himself and everybody around him makes them for him,” Farhadi says. “But in the end, he makes a powerful decision, and that’s how he becomes a hero to his own child.”

Early in the casting process, Farhadi tested a handful of nonactors for the role of Rahim. However, while many of the people seen in the final cut are individuals without prior acting experience, the psychological demands of the lead role made him reevaluate his original plan.

“I understood this is a very special character, because he’s a very simple man, but playing a simple person is much harder than playing a complex character. And then I thought that I have to bring a professional actor for it,” he notes. “If a simple character is not performed well, and his characteristics are not balanced enough, it easily turns into an idiot figure.”

Farhadi, who had seen Jadidi onscreen, asked the actor to workshop the part with him without officially casting him until he was certain the prolific thespian, from internationally recognized Iranian productions such as “A Dragon Arrives!” and “Cold Sweat,” could bring the subdued charisma that makes Rahim so endearing in his broken earnestness.

Another notable casting choice was Sarina Farhadi, the director’s daughter, who starred in his Oscar-winning “A Separation” a decade ago. As Nazanin, the creditor’s daughter, her actions greatly impact the narrative, and though her time in the film is limited, her motives are clear. Now 23 years old, Sarina helped her father as a sounding board while writing. “Through her,” he says, “I can understand more about the younger generation, her generation.”

Part of what she helped him grasp is how our internet interactions have significant social repercussions. Exploring the pitfalls of social media, nonetheless, wasn’t Farhadi’s first instinct. Yet, he argues that the nature of the plot organically made it a dramatic device.

Late in the film, a video of a violent incident threatens Rahim’s estimable status, thus his future hinges on its dissemination. Still, Farhadi’s view on the modern world’s ubiquitous exchange of information feels more neutral than fatalist.

“The voices of people that we couldn’t hear before now can be heard through social media. But, at the same time, there was so many voices going around that you have to be careful not to get confused about who to listen to,” he says. “Also, social media can bring people who are far away from each other closer and separate those who are physically close to one another.”

When situations like the one depicted in “A Hero” occur in small towns, the director explains, they gain prominence online, transcending regional interest. With that in mind, Farhadi decided it would be more believable if he set the story in a less densely populated place, rather than in bustling Tehran, where the majority of his preceding efforts took place.

Pedro Almodóvar and Penélope Cruz embrace the political and reclaim patriotism in ‘Parallel Mothers’

In a new film that blends his signature melodrama with a bold and moving look at a dark chapter of Spain’s past, Pedro Almodóvar gives Penélope Cruz another career best role.

In selecting Shiraz, a city in the southwest of Iran, Farhadi wanted to build a bridge between his contemporary saga about a man put on a pedestal and hero worship in antiquity. “A Hero” opens in the archaeological site of Naqsh-e Rustam, located a few kilometers away from Persepolis, where several rock reliefs exist of ancient Persian monarchs (e.g., Ardashir I and Shapur I) in valiant scenes and an inscription by Darius the Great.

“In my last movie, ‘Everybody Knows,’ I worked in a small Spanish village, and here I also wanted to get away from the capital, from the center of Iran. Shiraz is a historical city that is very popular among Iranians,” he says. “We feel certain nostalgia about our past through that city. There is a link between the history of that town and the concept of my movie.”

Aside from the immemorial wonders, Shiraz provided other, less monumental features. While scouting a store where multiple tense moments unfold, the director and his team came across a cultural bazaar where establishments have glass walls, which allow potential customers to look inside as they walk by. Finding this market also enabled Farhadi, known for dispensing with musical scores, to feature atmospheric diegetic music during an unnerving plot point, since one of the stores sold musical instruments.

It was that scene where the image of Charlie Chaplin, whose films Farhadi notes are very popular in Iran, can be discerned in the background. For the director, this was a good omen that made him think about the similarities between “A Hero” and Chaplin’s 1921 film “The Kid,” in which the Tramp’s selfless act of taking in and caring for an abandoned child backfires on him because of preconceived assumptions about his moral standing.

“It was really a gift from that location to me. I didn’t put that image there,” Farhadi says. “The person who owned that place, who was a very cultured person, had the picture of Charlie Chaplin, but I tried to put my camera in places where we could see that image.”

Farhadi was able to complete the casting for “A Hero” before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, but he was forced to postpone the rest of the preproduction for about 10 months. He spent the unexpected downtime analyzing and reworking the screenplay with the help of his brother, with whom he’ll meet often to talk about his progress and the adjustments or new discoveries he’s made.

One issue they encountered once production was underway was a populace wearing face masks in background shots. Farhadi wasn’t keen on including the global crisis, so the facial coverings were digitally removed in postproduction. “This is the movie of mine with the most VFX in it, but nobody has pointed it out so far, and I’m very happy of that,” he says. “The fact that you can make a realistic world using VFX was very valuable to me.”

In the decade since his fifth feature and irrefutable masterpiece, “A Separation,” won the Academy Award for foreign language film, Farhadi has directed films in France (“The Past”) and Spain (“Everybody Knows”) with global stars such as Bérénice Bejo and Penélope Cruz. He took home a second Oscar in 2017 for “The Salesman.”

“Ten years ago, around the same time of the year, I was in this same [Los Angeles] hotel, and I never thought my career in filmmaking would go this way. But I think that if all these things hadn’t happened to me, I would have continued on the same path,” he says. “The thing that is important about this is that these events helped for more people to watch my films. This is a big gift from life to me.”

The year’s best portraits of the actors, artists and culture figures who made 2021 memorable.

Farhadi doesn’t discount the possibility of ever working in the United States. Over the years, offers to direct TV series and feature films have come his way, but none of them have resonated with him so far. That’s likely because even the movies he has made away from his homeland subconsciously emanate from the issues his country faces.

“I don’t know from now on, but up to this point, I’ve tried to make my movies in my own country. Sometimes I make a movie elsewhere, but I always have it in my mind that I will return to Iran,” says Farhadi. “That’s the place where I was born and raised. That’s the place I know best. When I tell stories about Iran, I’m more emotionally invested.”

Farhadi prefers not to go into detail about a recent Instagram post where he expressed his repudiation of the Iranian government and its attempt to associate him with its ideology, citing that people outside of his country are likely not aware of the political intricacies of what he decried in the scathing open letter.

Nevertheless, the director did share an illuminating anecdote about his own experience as exterior forces tried to proclaim him a symbol or an ambassador for an entire people. Upon returning to Iran after winning his first Oscar, Farhadi was interviewed at the airport and asked whether he thought of himself as an Iranian idol representing the country abroad.

“I told them that I’m only a filmmaker, and I continue to say the same thing. It’s not that I’m trying to be humble. I really think that I’m just a filmmaker. If I accept the position that other people want to put me in, my life would become very hard,” Farhadi says. “If they make the image of a hero out of you, they take your ability to take risks in filmmaking. You would have to always make something that fits with the image they have of you.”

Los Angeles Times film critic Justin Chang’s best movies of 2021 include ‘Drive My Car,’ ‘The Power of the Dog’ and ‘The Green Knight.’

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.