How miscast is Nicole Kidman as Lucille Ball? Digging into the highs and lows of ‘Being the Ricardos’

Aaron Sorkin told Mark Zuckerberg’s origin story in “The Social Network” and explored the rise of Apple in “Steve Jobs.”

Now, in “Being the Ricardos,” he turns his gaze to a different kind of visionary: Lucille Ball.

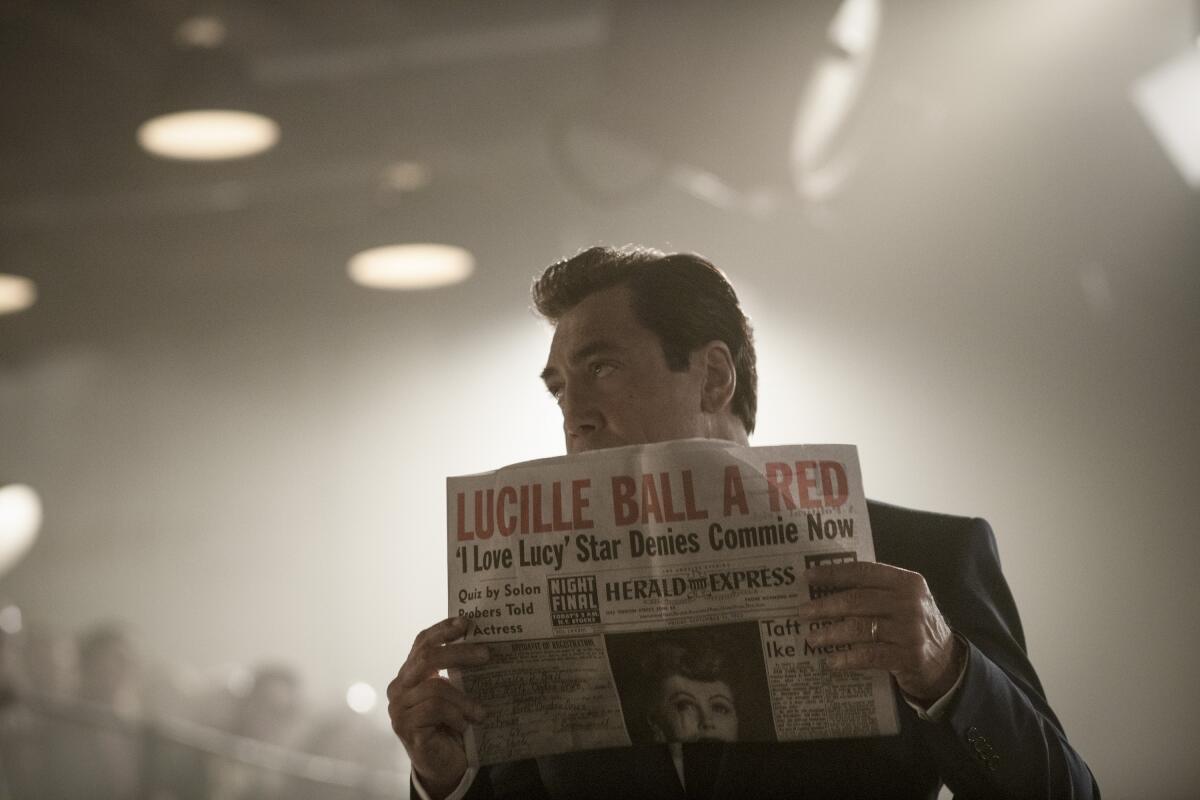

The movie, now available to stream on Amazon Prime, follows a single tumultuous week in the lives of America’s favorite redhead (played by Nicole Kidman) and husband Desi Arnaz (Javier Bardem) in 1952. While filming an episode of their hit sitcom, “I Love Lucy,” the couple deals with a string of crises — including rumors of infidelity, a congressional investigation into Ball’s past affiliation with the Communist Party and a pregnancy that could spell doom for the show at a time when being visibly with child was considered taboo. (No, these things did not actually happen all at once. It’s dramatic license.)

The supporting cast includes J.K. Simmons as the cantankerous William Frawley (who played neighbor Fred Mertz), Nina Arianda as a frustrated Vivian Vance (a.k.a. Ethel Mertz) and Alia Shawkat as writer Madelyn Pugh.

Hollywood loves a biopic, especially one that also happens to be about the industry. “Being the Ricardos” has all the trappings of an awards favorite — but the casting of Bardem and Kidman has also raised eyebrows.

Times staff writer Meredith Blake and culture columnist Mary McNamara analyze just how much of that skepticism was justified.

Aaron Sorkin explores the personal and professional lives of the iconic “I Love Lucy” stars in Amazon’s “Being the Ricardos.”

Meredith Blake: When this movie was announced back in January, the prospect of Nicole Kidman — an excellent actress who can be quite funny but not one exactly known for her kinetic physical comedy or rubber-faced expressions — playing the beloved Lucille Ball got a lot of people riled up. I will admit that I was less concerned about the Kidman part of the equation than the “written and directed by Aaron Sorkin” part. A story about a trailblazing female performer at the height of her power, and during a pregnancy that would quite literally change the TV industry, told by a filmmaker with a tendency for portraying ambitious women as neurotic lunatics? No thanks!

I will say that “Being the Ricardos” did not make me as stabby as I expected it might. There is something about hearing Sorkin’s trademark speeches coming out of the mouth of a woman and not, say, a middle-aged white male newscaster that automatically makes them feel less grandstanding. To his credit, Sorkin is clearly eager to present a complicate portrait of America’s sweetheart, portraying Ball as a prickly, demanding pain in the butt who can get away with it because she is a once-in-a-century comedy genius. It’s so rare that women get the “A Beautiful Mind” treatment (see: virtually every biopic about an artist, musician, writer or scientist ever made) that I think it’s something to celebrate, even if almost everything else about the movie disappoints.

Let’s start with the obvious: Kidman and Javier Bardem are generally excellent actors who are, nevertheless, wrong for the roles they are playing. How anyone thought these two could capture the spirit of Lucy and Desi — especially when Kathryn Hahn and Jaime Camil were right there! — is beyond me.

Perhaps the participation of these Oscar winners helped convince Jeff Bezos to spare some of the money he’d otherwise spend going to space for a few seconds. I was also baffled by the documentary conceit, which falls apart under the slightest bit of scrutiny. When was this nonexistent documentary supposedly made, exactly? Why does it look like the present day, when all of the people involved are long dead? The whole device strikes me as a clumsy way for Sorkin to deliver some expository dialogue that was probably superfluous anyway.

I was also troubled by the way the movie makes J. Edgar Hoover into a redeeming hero who salvages Ball’s reputation. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Mary, what did you make of it all?

Mary McNamara: Kathryn Hahn! Never have I longed for her so much as in every minute of this film, which I spent searching for a single glimpse of someone resembling Lucille Ball.

Biopics are definitely tough for actors — that’s why such a large proportion of Oscars go to biopic performances — and “Being the Ricardos” has an extra level of difficulty. Kidman is playing a character who was also playing a character, and the gap between Lucy Ricardo and Lucille Ball is extremely wide already, while the gap between Lucy Ricardo and Nicole Kidman is not so much a gap as the Grand Canyon. Kidman is known for taking big chances, but this particular combination proved, alas, beyond her ken, and she couldn’t land either of them.

No one could capture the deceptively quicksilver genius of Ball, but Kidman’s characteristic snow-maiden, “ready for my close-up” stillness is, as you say, antithetical to the versatility and raw palpable energy Ball harnessed to become the most powerful woman in television. Also, and I realize I am not the first person to say this, the film is rarely if ever funny, in large part because Sorkin never allows Kidman, who is a talented comedic actress, to be funny. It’s as if the assignment was “play Lucille Ball and get no laughs.” Which is a huge problem.

In a weird way, Bardem was a fine foil for Kidman in that he, too, was playing an alternate-universe version of Desi/Ricky — a believable Desi would have actually made things worse, and they do come alive as a couple. Just not the couple referenced in the title.

As for the structure, well, I will forgive most things if it means I get to see the great Linda Lavin (as the elder Madelyn Pugh), even briefly, so the documentary setup didn’t bother me. Sorkin chose to focus on a single week, in which Ball was being harassed, and potentially blacklisted, by the House Un-American Activities Committee, which allows Sorkin to do what he does best — lambast the worst facets of American politics.

For dramatic purposes, he also chose to make this the same week the producers/stars demand that Lucy’s pregnancy become part of the show, even as Lucy is devastated by reports that Desi has been unfaithful. All of these things happened, just not at the same time. If another person had made the film, the tension between the couple’s revolutionary demand to make their television marriage more realistic as their real marriage faced collapse might have resulted in something more emotionally interesting (and — added bonus — the ghastly appearance of J. Edgar Hoover as a white knight would be unnecessary). But Sorkin is Sorkin. I didn’t know the whole “Lucy is a communist” storyline, so that was interesting to me, especially at this particular moment in time. Certainly the desperate play to swing public approval felt horribly current.

I was a bit concerned with the way William Frawley (J.K. Simmons) became the font of all wisdom, often at the actual expense of Vivian Vance (Nina Arianda), who spent much of the film worried about her looks, or how the younger Madelyn Pugh (Alia Shawkat) was used as a mouthpiece for concerns that the Lucy character was infantilized. Simmons, Arianda and Shawkat are all perfectly splendid, so I’m happy they had things to do, but ... what did you think?

Nicole Kidman and Javier Bardem play Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in Aaron Sorkin’s latest hyper-articulate behind-the-scenes drama.

MB: You’re right, Kidman doesn’t get to be funny, which is unfortunate. But I will give her credit for nailing Lucy’s husky smoker’s voice (brought to you by Philip Morris, just like the show!).

I agree that the supporting cast, while superb, wasn’t necessarily used very well. The Vivian Vance-wasn’t-really-frumpy storyline felt reductive instead of empathetic — and as for Shawkat, I am pretty sure almost no one used the word “infantilize” in casual conversation in 1952.

I don’t really take issue with how Sorkin fudged the timeline to make it seem like all these things happened in the same week. (Even though it again makes me wonder why there’s a documentary being made about a week that didn’t actually happen this way. Sorry, Mary, I am not letting this one go. Linda Lavin notwithstanding.) I much prefer a biopic that focuses on a discrete chapter in a person’s life rather than giving us the cradle-to-grave narrative. Compressing the timeline allowed him to explore thematic threads in this story, so be it.

Yet even with Sorkin’s historical embellishments, I still found the whole thing dramatically inert. Maybe it’s because I already know that Lucy and Desi ultimately got divorced, that CBS OK’d the pregnancy storyline and that Ball continued to have a thriving career despite the best efforts of Walter Winchell and his ilk. I never felt like much was at stake.

Besides, Lucy herself never seems that worried about the potential fallout from her brief flirtation with communism. Instead, she is far more concerned with making sure every joke in the show lands. She’s particularly fixated with a scene in which Lucy is trimming some flowers to place on a dinner table before the Mertzes come over. Sorkin repeatedly takes us into Ball’s head as she envisions better, funnier versions of this scene. It’s a clever way to illustrate her comedic brilliance and preternatural understanding of the art form.

Yet it all falls flat because almost none of Lucy’s suggestions make the final version of the episode they’re filming — a choice I found utterly bizarre. If this is a film about a creative genius, wouldn’t it make more sense for Lucy to obsess over seemingly insignificant details that do wind up in the show and ultimately make it funnier?

Are we supposed to believe Sorkin’s imagined version of this episode would be better than the real thing? Is he doing to “I Love Lucy” what he did to TV news with “The Newsroom” — saying, effectively, “Here’s the better version I wrote with the benefit of hindsight”? If so, that’s some serious chutzpah!

Am I wrong here?

MM: You’re not wrong regarding the result, but I don’t know about the intention. Sorkin has a very singular narrative structure and syncopation, one that is very different from — to the point of being at odds with — the broad theatrical comedy of “I Love Lucy.” The show, and indeed Ball’s brand of comedy, is not the focus of “Being the Ricardos”; he is more interested in exploring Lucy, and Desi, in terms of power rather than artistry. I loved the scenes that showed the hard work of an artist, how every movement and line was crafted, but I wish the film took the art itself as seriously. We are told, repeatedly, that Ball is the most beloved star on television, but we never see why. In focusing on the mechanics of the balancing act, the film loses sight of the magic. And that’s a damn shame.

I’m not saying looking at Lucy and Desi’s partnership in terms of power isn’t interesting — they were an astonishing pair, and the fact that they had the power they did is pretty miraculous. Which is why the film was, for me, such a disappointment. Though it moved along at a Sorkin-ian fast clip, pulling this thread and that, in the end, it felt more educational than inspirational. It hit all the marks of Ball’s remarkable story, but it didn’t seem all that interested in who she was, what made her so beloved.

Yes, she was a hard-ass, but she also was a full-body performer who was not afraid to pull her heart out for the laugh. Sorkin’s humor is cerebral, all caustic wit and clever asides. Which is great. But Ball and Arnaz were the exact opposite — enormously physical, overwhelmingly emotional. I guess that was my problem with the film; for all the relationships it chronicled, it had no real heart.

The costumes, on the other hand, were terrific.

MB: Indeed. It’s time for me to invest in some trousers.

Aaron Sorkin’s biopic of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz takes some liberties with the truth. We examine the film’s treatment of three real-life events.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.