Netflix drama ‘7 Prisoners’ looks at enslavement in Brazil. Its director hopes for global action

For Brazilian American filmmaker Alexandre Moratto, a little deceit — born of a zeal for film — was necessary to make a life-altering creative connection.

While studying at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in 2007, Moratto met Iranian American director Ramin Bahrani, who was searching for assistance in casting the Latino parts in his project “Goodbye Solo.”

“He needed an intern who was over 18 years old and who spoke Spanish, neither of which I was or did. I was 17 at the time. I didn’t speak Spanish. I spoke Portuguese. I lied to him,” said Moratto, who had skipped a grade and entered college at an age younger than most of his classmates.

Now, with two award-winning features to his credit, Moratto occupies an enviable position among the cinematic storytellers to recently emerge on the global stage. His latest, “7 Prisoners,” a scorching social realist drama on modern-day slavery, debuted at No. 2 on Netflix’s weekly list of most watched non-English language films worldwide.

Even in his youth, Moratto showed an ambition to achieve his goals. He learned Spanish on the job with Bahrani, and the established filmmaker took notice of the plucky boy’s determination.

“I was drawn to him. I thought he was very motivated, very intelligent,” Bahrani recalled. “He seemed to want to be a filmmaker more than anything else in the world.”

Watching Moratto’s student short films, Bahrani encountered impressive humanism and poetry. “Ramin said my shorts had vision, but I needed to learn how to write a script and tell a story,” Moratto noted. “He really helped me understand narrative storytelling.”

From their many conversations on life and creativity, Bahrani sensed the young talent would benefit from delving into his background and suggested that rather than moving to New York or Los Angeles after film school, he relocate to Brazil.

“I lived in Iran for three years when I graduated college, it was a pilgrimage towards my identity and also a cinematic pilgrimage,” explained Bahrani. “I knew he was very interested in Brazilian cinema and I thought he could find himself, his cinema, his voice, at least some part of it, there.”

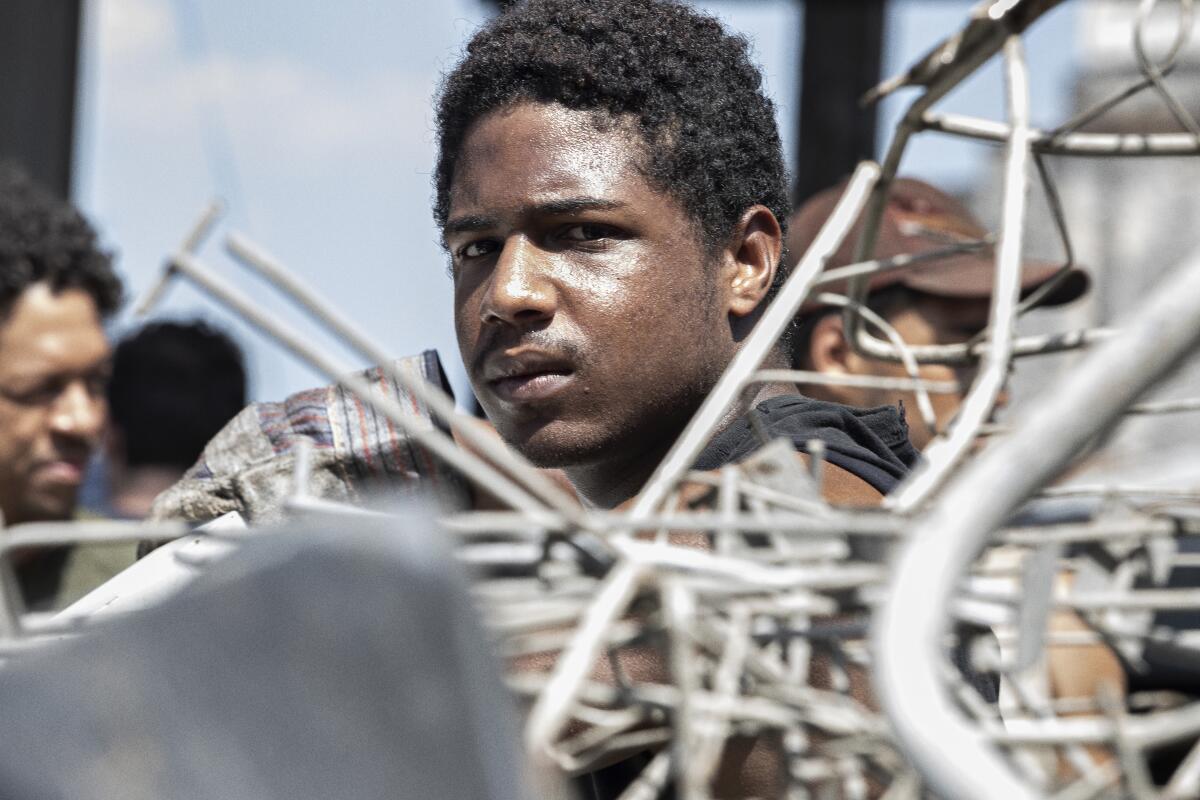

Teenage boys from the Brazil countryside are forced into working in a scrapyard in São Paulo in the thriller ‘7 Prisoners,’ starring Rodrigo Santoro.

After a youth spent constantly on the move — Moratto recently tallied 30 different addresses he’d occupied — his time in Brazil began to crystalize certain things. He gained a more robust understanding of the country’s marked economic disparities, and in turn the opportunities his mother wanted to afford him moving to the United States.

Moratto’s work as a volunteer for Instituto Querô, a UNICEF-supported non-governmental organization in Santos, Brazil, for at-risk youth, was key to the realizations. Its participants acquire interpersonal and professional skills through hands-on courses in filmmaking and the encouragement of dedicated social workers. While sharing his passion with teenagers there, Moratto witnessed their resilience in the face of extreme poverty and limited access to education.

“That really inspired me. I started volunteering very young, I was 19, and they were my age,” Moratto said. “I wanted to make a film with them to honor that youthful dream we had of one day making something together.” The outcome of their collaboration was Moratto’s critically acclaimed debut, “Socrates,” centered on a queer teen without a safety net searching for understanding in a precarious and hyper-masculine environment.

Following a notable festival run, “Socrates” earned Moratto the Someone to Watch Award at the 2019 Independent Spirit Awards. It was the same prize Moratto’s hero, Bahrani, had received for “Chop Shop” a decade earlier. And the unrestricted grant offered reprieve from the debt he incurred paying for part of the production out of pocket.

The authenticity and honesty of “Socrates” was rooted in the involvement of individuals who empirically understood the character’s circumstances. Moratto has contemplated the implications of making stories not just about but with those traditionally excluded from the storytelling process.

“The reality is that a lot of filmmakers who make this type of film come from situations of wealth or privilege. I identify as middle class in the U.S. But in Brazil, of course, I’m very privileged, especially compared to the people who I’m depicting on the screen,” said Moratto. “For me, the way I work with these communities and the people that are being represented is by including them in the film — not just in tangential ways, but in deeply meaningful ones.”

Two of Moratto’s closest creative partners today emerged from his involvement with Instituto Querô: actor Christian Malheiros, the lead in both “Socrates” and “7 Prisoners,” and co-writer Thayná Mantesso, whom he credits for both films’ true-to-life dialogue.

Set on casting a lead from overlooked areas of São Paulo, Moratto auditioned Malheiros, at the time a young Black thespian honing his craft in local theater, before seeing 1,000 more prospective actors from neighboring schools. In the end, Malheiros’ charisma and disposition to take direction landed him the part.

As Moratto recalls, “I remember asking him, ‘What do you want from this?’ And he turned to look at me and said, ‘I want to become a worldwide reference to people like me.’ I thought that was such a beautiful thing for him to say.” Turning their contributions to Moratto’s films into fruitful careers, both Malheiros and Mantesso are now part of Netflix’s Brazilian hit series “Sintonia.”

After the success of “Socrates,” Bahrani shared with Moratto a lesson he’d received from Iranian master auteur Abbas Kiarostami: “If you make a movie, make sure you make the next one very quickly. Don’t delay.”

Moratto’s follow-up, “7 Prisoners,” which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September, initially arose while he was finishing “Socrates” in 2017. Moratto, an insomniac, had turned on the TV in the middle of the night and came across images he could not fathom.

“It was footage of a young man and he had a chain tied to his ankle and he was forced to work for no pay in a factory in São Paulo, a massive global alpha city,” Moratto said. “This footage was from the 21st century. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I couldn’t believe that enslavement still existed like that.”

Disturbed, he looked for everything he could find about human trafficking and modern-day enslavement. This impromptu groundwork culminated when he shadowed a friend conducting a research project on the subject for the United Nations and Brazil’s department of labor. Over the course of a week, Moratto heard the stories of around 60 survivors of the horrifying, clandestine enterprise.

Their tremendous strength in relaying the dehumanization they had endured convinced him to pursue a film told from their perspective.

“City of God” director Fernando Meirelles, who came on board as an executive producer of “Socrates” after a partner at his company O2 Films recommended watching Moratto’s work, is also a producer on “Prisoners.” Moratto praises “City of God” as his first taste of social realism, and the influence of not just Meirelles and Bahrani but also the late Brazilian master Héctor Babenco — namely his seminal 1981 film “Pixote” — can directly be felt in Moratto’s films.

“The story was based in lots of people who told him stories, and ‘City of God’ was a lot like that for me,” Meirelles noted. “Back then I worked with all the boys to create the story and then to act it. In a way Alex went the same route in both ‘Socrates’ and in this film now.”

With Malheiros returning as protagonist, “7 Prisoners” chronicles the nightmare of a group of young men from the countryside, some of them illiterate, deceived into working as forced labor at a scrap metal junkyard. Malheiros embodies Mateus, an innate sharp leader ambivalent about his allegiance to his fellow victims and the chance for personal advance at their expense.

“We were looking at all the different layers of power, all the different layers of corruption, and we do know power goes up the ladder all the way to the top and then back down and around again, it’s cyclical,” said Moratto. “We see this in politics. We see this in institutions. We see this everywhere we go, and it’s true for the systems of enslavement.”

Meirelles says the film gives Moratto an even greater opportunity to demonstrate his skill.

“He shot ‘Socrates’ with 30,000 reals, which is around $12,000,” said Meirelles. “I thought, ‘The guy really knows how to do it because he had no money, no professionals, no nothing and it’s such a solid film. What would happen if he got some money and if he had some structure around him?’ That’s why we got involved.”

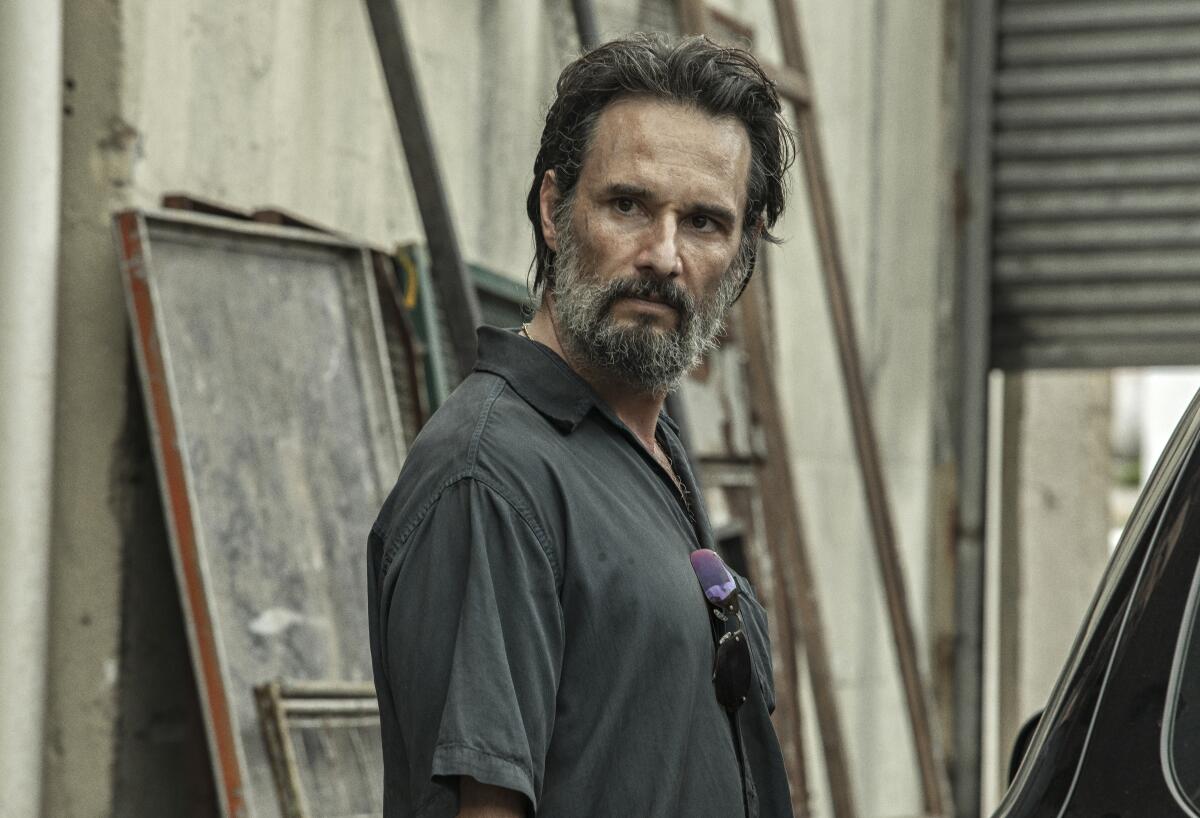

Meirelles’ endorsement also convinced Brazilian star Rodrigo Santoro, who crossed over into the global market with “300” and “Love Actually,” to consider the key part of Luca, the perverse captor inflicting violence and humiliation on his hostages.

Moratto’s interest in the actor emanated from his role as a transgender woman in Babenco’s gritty prison drama “Carandiru.” Though Santoro initially had doubts, he was lured by the layered character.

During a three-hour meeting, the performer and filmmaker agreed the goal was to humanize an apparent monster, but not absolve him. “Rodrigo and I talked about that a lot because the first impulse is to hate that man, to want to make him a psychopathic villain, but that’s not what he is,” said Moratto. “He’s a person with a family and a job. It just so happens that his job is quite deplorable.”

“This is a character that doesn’t have redemption. He clearly represents the oppressor in the film. He lives off the exploitation of his workers. He’s aware of the terrible things that he does, but he is also a survivor and a product of an unequal and exclusionary system,” noted Santoro. “We tried to tell the story in a way that he was not just a one-dimensional villain and at the same time not excuse him for the things that he did. That was a challenge.”

“What I really like about the film is that it’s not only a story about bad people and good people or both exploitation and people exploited, but it also talks about how power corrupts us,” added Meirelles. “It’s about how far we go to find out what our principles are.”

Heartened by the positive reception for “Socrates” in Brazil, Moratto hopes “7 Prisoners” is granted similar enthusiasm, even as an unflinching examination of social ills. “It’s tough to look at ourselves,” said Moratto. “It’s tough to accept societal flaws, but the reality is that enslavement happens in the entire world, so I’m not just talking about it in Brazil, I’m also talking about it worldwide.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.