Andrew Garfield was exhausted and upset. It had been weeks since Lin-Manuel Miranda pitched him on starring in a musical and invited him to a workshop of the still-being-written script — an unconventional step for any screen project but a highly informative tool for theatermakers like Miranda. But it was scheduled for the day after Garfield closed Broadway’s “Angels in America,” in which he played the tormented lead, and the role left him desperate to rest and recover.

“Perfect, so that means you’re available,” Miranda excitedly told Garfield. “You don’t have to sing if you’re too tired or nervous. We’ll just read through it together and see how it goes.”

Reluctantly, Garfield agreed to participate, and sat down with a handful of Miranda’s actor friends in a back office at the United Palace in New York’s Washington Heights.

“Two hours in, I’m having the time of my life in what was essentially a healing musical theater sound bath,” recalled Garfield, who, with Miranda’s gentle guidance, was starting to sing by the end of the weeklong workshop. Two more were held before filming began, which allowed Garfield and the other actors to establish a trust in the material, in each other and in Miranda.

“We felt like we were all in really great hands, which isn’t hard to feel because he is who he is,” said Garfield of Miranda. “Lin is an elemental force who doesn’t seem to need to sleep, who has this gleeful urgency when it comes to something he loves and who genuinely believes that anything is possible. It’s contagious.”

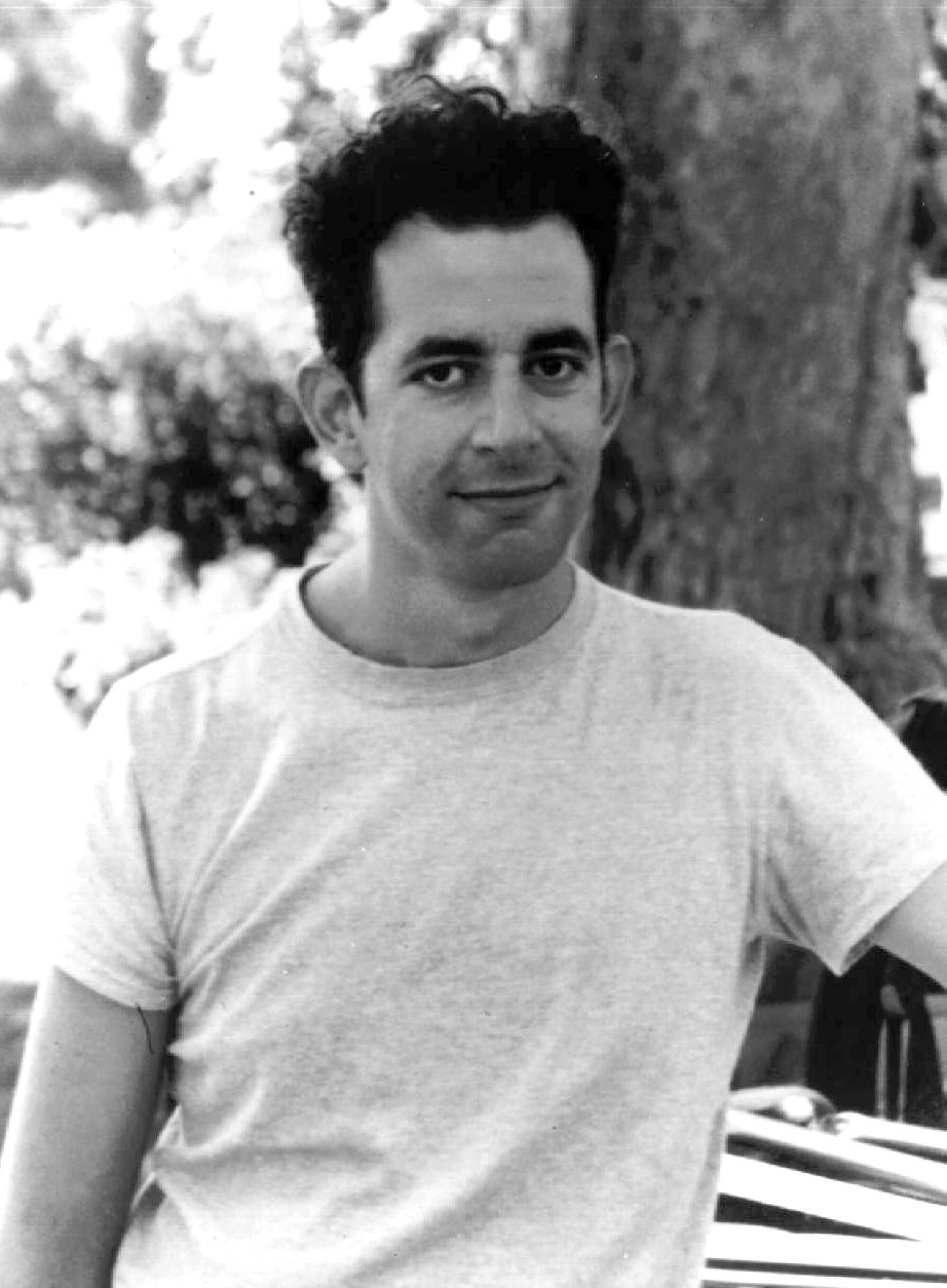

These same descriptors can be applied to the project’s author and main character: Jonathan Larson who, before creating the groundbreaking show “Rent,” spent the early 1990s developing and performing a solo work that became known as “Tick, Tick … Boom!” The semiautobiographical rock monologue is about a composer-lyricist who aims to take the industry by storm with what he believes to be a musical masterpiece.

“For anybody who is working toward something, there are those moments where you’re supremely confident, and then the next moment, you’re just absolutely full of despair and doubt of whether you’re ever going to be understood,” said Julie Larson, Jonathan’s sister. “And sometimes you don’t realize how your passionate, single-minded focus on a goal is impacting the people around you, and stopping you from seeing what’s really important.”

At first glance, “Tick, Tick … Boom!” does not have the explicit makings of a successful movie musical: Its source material is an unfinished one-man show that, after Larson’s tragic death in 1995, was reconfigured into a three-actor production; its main character is a charismatic but arguably self-obsessed creator navigating a niche field. Also, Miranda had never directed a major movie, and Garfield, who portrays Larson, had never sung in public before that first workshop.

But Miranda, also a musical visionary with a steadfast resolve, had asserted for years that a “Tick, Tick … Boom!” adaptation is “the only film I already knew how to make,” he told The Times. Currently in theaters and launching Friday on Netflix, the result “feels refreshingly intimate and specific, idealistic but rarely naive, and grounded in a way that gives an unexpected lift to its flights of fancy,” according to Times film critic Justin Chang. “Miranda’s talent for putting on a show has never been in doubt, but it takes a subtler dimension of talent to make this ostensibly small one feel big.”

This authentic expansion is achieved largely because of an unabashed embrace of the real Larson, who was inherently theatrical. His friends and family describe him as exuberant and generous, spontaneously making up songs about whatever was in a room and spending what money he had on celebrating his loved ones. His joie de vivre was matched by his mission to create a notable work of art. If only producers would discover his greatness at his upcoming presentation, conveniently scheduled for his 30th birthday.

“He believed in his own talent, but he had this profound terror that no one was ever going to pay attention,” said screenwriter Steven Levenson.

“Story-wise, it made sense to show the mind of this guy who is extravagant and spectacular but also frenetic and filled with anxiety and worst-case scenarios. Am I spending my time the way I’m supposed to? What if this thing that I’ve spent the past eight years writing is all just a waste? If another door gets slammed in my face, do I keep going or do I finally listen to all the signs and do something else?”

Miranda, now 41 years old, has asked himself these very questions for decades, especially while encountering Larson’s work. On his 17th birthday, he saw “Rent,” a show that directly inspired “In the Heights.” Watching “Tick, Tick … Boom!” in college clarified his purpose to pursue theatermaking professionally.

His performance in the 2014 City Center Encores! production of the show caught the attention of producer Julie Oh, who immediately pursued its film rights. “No one understands the themes of this story better than Lin does because he has lived it,” said Oh of Miranda.

And of course, Miranda — who also penned songs for Disney’s “Moana,” “Encanto” and the upcoming live-action “The Little Mermaid” as well as Sony’s “Vivo” — had a firm grasp on the interiority of trying to compose a song, and the irreplicable satisfaction of finally having written one.

“He could be a real pain in the ass because he was impatient and frustrated,” said Miranda of Larson. “But when he was teaching songs to actors and rehearsing and performing, it was like seeing a fish go back into the water, because he was doing what he was put on this earth to do. I understand that. I’m lucky enough to get to do this for a living, but I know I’d be writing songs no matter what, because it’s my calling.”

Lin-Manuel Miranda makes a fine feature directing debut with this Netflix adaptation of a musical written by and about ‘Rent’ creator Jonathan Larson.

Miranda drew from everything he knew about theater to make the stage-to-screen translation of “Tick, Tick … Boom!” as authentic as possible. It begins with “30/90,” a thrilling introduction to Jon that quickly switches between his actual reality — a diner day job, a pile of bills, countless rejection letters and a looming deadline — and his heightened perception: an animated apartment duet with his best friend, Michael (Robin de Jesús); a dance sequence in the Strand bookstore with his girlfriend, Susan (Alexandra Shipp).

“Sometimes you’re seeing something as it may have happened in his life, and other times you’re seeing what he imagines in his head,” said Miranda, who sprinkled the scene with visual motifs that recur throughout the movie.

“I found that editing is similar to composing a theater score: playing with tempo, tension and release; figuring out when to stay in a moment, when to zoom past it and when to return to it. It was the thing I was most scared of but turned out to be incredibly analogous to what I know how to do.”

A thorough exploration of Larson’s demo tapes, notebooks and other archival materials at the Library of Congress informed the film’s setlist; songs cut from the stage show were added to the movie (“Boho Days,” “Play Game” and “Swimming”) while others were left out (“Green Green Dress,” “See Her Smile” and “Sugar,” the latter cut down to a jingle).

Every included musical number — regularly performed onstage with just a few instruments — has a uniquely rethought arrangement, ranging from just a tweaked drum groove to turn “Louder Than Words” into an anthemic call to action, to a grandiose interpretation of “Sunday,” sung by a star-studded chorus and accompanied by a whopping 61 musicians.

“It was fun to go to those extremes because you’re not going to find a 30-piece string section in an off-Broadway house,” said executive music producer Alex Lacamoire, who spearheaded the film’s orchestrations with Bill Sherman. “If we added an organ or strings or reeds, we made sure they’re there for a reason.”

Echoed Sherman, “All of Jonathan Larson’s songs are epic and melodic and perfect, so the goal was to never mess with the soul of the song but just do what we can to help his initial genius shine through even more.”

With Joshua Henry, Vanessa Hudgens and MJ Rodriguez among the cast, each song has a distinct narrative setup, as Jon wrestles with his commitment to art while in seemingly magical swimming pools and ’80s rap music videos.

“There’s the truism that your opening number establishes the rules of the story and the relationship to the audience,” said Miranda. “But what I learned on ‘Hamilton’ is that, actually, every number afterward is a new opportunity to f— with that relationship. Six songs into ‘Hamilton,’ we go, ‘Actually, we reserve the right to stop time and reverse it.’”

For example, the accelerating “Therapy” borrows the “Cabaret” strategy in juxtaposing the comical duet onstage with a newly written fight between Jon and Susan, a dancer derailed by an injury.

“She understands that being in love with him means that his art will always come first,” said Shipp, who plays a much more fleshed-out version of the character. “But she’s an artist too, and he’s just not listening. We all want to know that we’re not wasting our time with someone.”

Film critic Justin Chang and theater critic Charles McNulty explore what this year’s abundance of movie musicals says about the state of the form.

And the gradually vibrant “No More” parallels “The Wizard of Oz,” as Michael, an actor turned advertising executive, moves from Jon’s shabby six-story walk-up to a high-rise apartment worthy of a slow-motion sequence. “Physically, it was so hard because we had to film it in double-time,” said de Jesús, who made sure not to play Michael as a sellout.

“Some people have this weird idea that when you leave the arts, it’s a failure, to the debilitating point that people stay in this business and are deeply unhappy. It’s a trigger for Jon but not for Michael, who is much more practical and, like Susan, is figuring out their idea of success.”

These fantastical framings make the relatively unadorned “Why” all the more powerful. “It’s when he realizes how he wants to live his life,” said cinematographer Alice Brooks of the 11 o’clock ballad, which Garfield sang live at the Delacorte Theater. “Because the moment is so pure and raw, it became very clear that the simpler we filmed it, the better it was.”

On set, Miranda was what de Jesús called “pure and joyous,” with a “childlike excitement that made me that much more excited to try whatever he came up with,” said Shipp. He’s not a man of many takes, and he knows when he has the shot. “That instinct is something I’m still honing, because it’s my first movie,” said Miranda. In comparison to other directors, Miranda “is extremely open-minded to the point he is constantly solicitous of knowledge from others,” said producer Brian Grazer.

That includes his own kids. Miranda was revisiting the “Why” sequence with editor Myron Kerstein from his Washington Heights home, where he lives with his wife Vanessa Nadal and their two sons, when his youngest wandered into the room.

“He sits in my lap and watches Jonathan run through Central Park with this anguish, and the music is loud and scary. He jumps the fence of the Delacorte, pulls the tarp off the piano and sits down. And in that quiet moment before he puts his hands on the keys, my 3-year-old goes, ‘The piano will make him better.’

“I burst into tears,” said Miranda, getting emotional. “The 3-year-old gets it, the sequence works! That Frankie had that insight while watching this unfold — that will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

Julie Larson was similarly emotional while watching the movie alongside Jonathan’s friends at its world premiere at AFI Fest in Los Angeles. “I really felt like I got to sit and share time with my brother: Johnny, the multifaceted person who was passionate about what he did, and was also playful and a great friend and uncle,” she said. “It was beautiful to see him as a fully rounded person, instead of just this guy who wrote ‘Rent.’”

Like his previous encounters with Larson’s work, making this movie has yielded Miranda yet another clarifying directive. “I learned a couple of things about what I want to do, which is that I love telling musical stories onscreen,” he said with a smile.

“Jon [M. Chu] can direct ‘Wicked’ — I don’t need that pressure in my life, he thrives on it! I’ll make the smaller, stranger musicals that wouldn’t otherwise get a green light. If I’m lucky enough to do that, I’d be so happy.” It’s a pledge best expressed by Larson’s lyrics:

Hey, what a way to spend a day

Hey, what a way to spend a day

I make a vow, right here and now

I’m gonna spend my time this way

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.