Five years ago, after completing his second film, “Gook,” an intersectional revisiting of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Justin Chon pondered what to pursue next. That’s when the American director of Korean descent became aware that international adoptees brought to this country by U.S. nationals were being deported given their lack of permanent status.

“I thought, ‘I’m sure they can clear it up because obviously they’re adopted by U.S. citizens. It shouldn’t be a big deal.’ But then I found out that it didn’t matter, they were using it as a loophole to deport them,” Chon told The Times. “My heart bled for them. It must be absolutely painful to think that you were taken from the country you were born in, and then many years later, the country that you call home says that you don’t belong.”

Upon researching the issue at length, Chon realized the situation had been ongoing for several administrations without resolution. Adoption didn’t guarantee these individuals American citizenship, and now thousands find themselves in a legally vulnerable position.

Chon’s desire to elucidate this shocking injustice became the foundation for the director’s latest work, “Blue Bayou,” which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in July and is now playing in theaters nationwide. Based on that kernel of an idea, Macro, a production company whose mandate is to finance and produce stories told through a multicultural lens, came on board and commissioned him to write the screenplay.

“We tend to get a lot of immigration stories with the usual narrative dealing with the border and Mexico,” said Poppy Hanks, Macro’s executive vice president of film production and development and a producer on the film. “Thinking about what was happening at the time in the country, here was a way to tell this story that not only a lot of people didn’t know about — so we could educate — but also in a way that was unusual.”

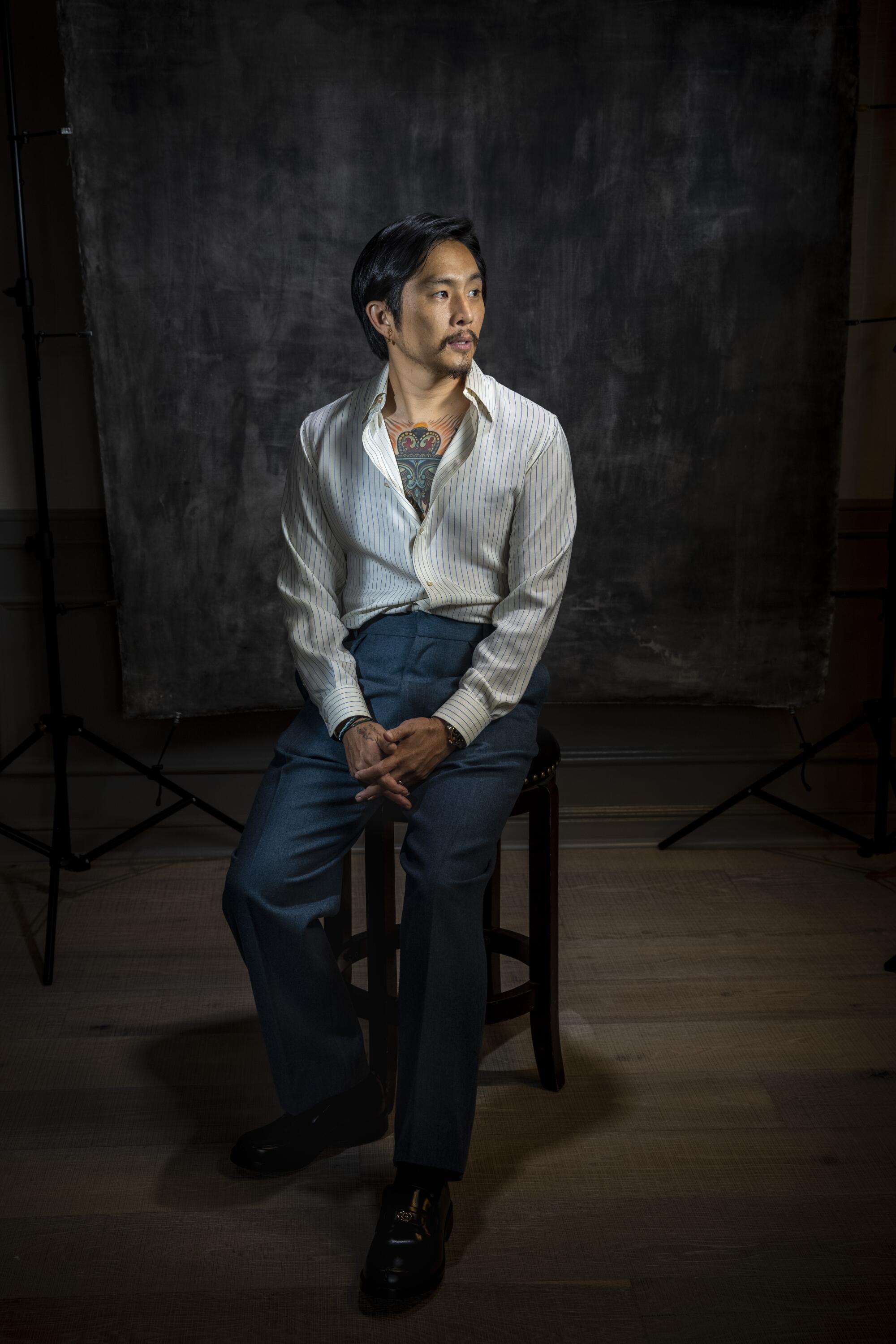

Justin Chon wrote, directed and starred in this uneven but devastating film about a Louisana man facing deportation from the only country he’s ever known.

As Chon developed the project, he completed a third independent feature, “Ms. Purple,” a portrait of a young Korean American karaoke hostess navigating family dynamics fraught with resentment, which premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival and was released the same year.

Soon after that film opened, production began on “Blue Bayou,” the story of Antonio LeBlanc, a New Orleans man (played by Chon himself) adopted from South Korea by a white American couple as a child, now confronted with the possibility of forced repatriation to a land he barely remembers. A tattoo artist with a past of illicit activity, Antonio is a devoted stepfather to Jessie (Sydney Kowalske) and partner to longtime girlfriend Kathy (Alicia Vikander), pregnant with their child. Separation from his family is an unbearably nightmarish prospect.

There are several reasons why the Orange County native, whose previous two films made deliberate use of their Los Angeles settings, chose to center this story in Louisiana. “I had never seen an Asian American with a Southern accent played in a particularly significant way in film, and I also wanted to put it in New Orleans because it’s a very resilient city,” Chon said. “Even recently they dealt with a hurricane and they still find a way to keep their spirit alive. That really represented Antonio. He’s a real three-dimensional human, not just some saint.”

Since the Vietnamese diaspora is the largest Asian population in Louisiana, comprising refugees relocated there in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and their American-born children and grandchildren, Chon opted to portray two distinct Asian ethnicities in the narrative. Antonio establishes a platonic bond with cancer patient Parker, played by Vietnamese-born French actress Linh Dan Pham (“Indochine”).

“I had never seen an Asian American with a Southern accent played in a particularly significant way in film ... He’s a real three-dimensional human, not just some saint.

— Justin Chon on his character in “Blue Bayou”

Location specificity aside, Chon focused particular attention on the proper depiction of the adoptee experience, specifically those of Asian heritage raised in white households. ”I wanted for them to feel like they were represented correctly, so I had a lot of consultants and people who were a sounding board for me throughout the process of writing the film,” said Chon.

One of those voices was Julie Young, a former lawyer and founder of the Brooklyn-based TIDE Film Festival for underrepresented storytellers. She befriended Chon at the 40th annual Asian American International Film Festival, where she was asked to present him with an award. Subsequently, she became a trusted guide, sharing her worldview as an adoptee and connecting him with others in the adoptee community.

“That night in my speech, I talked about the importance of representation and what would it have looked like if as an adoptee I had grown up seeing Korean adoptee stories or really any adoptee stories in the media — and the significance of Justin’s work, because he’s showing a side of Asian America that’s not usually seen,” explained Young.

Through their conversations, Young recalled memories of growing up in a white family and in a suburban community, as well as the earth-shattering relevance of becoming a mother. “When I had my kids, I have twins, and I saw my son, the first words out of my mouth were, ‘He looks like me,’” she noted. “This is a super significant thing — in my experience and a lot of my adoptive friends — because we grow up always wondering, ‘Who do we look like?’”

Directly addressing this sentiment, “Blue Bayou” features Antonio holding his newborn child for the first time, a moment that strongly resonated with Young. In turn, the film challenges some of what Young considers major misconceptions about adoption through Antonio’s estranged and traumatic relationship with his putative parents.

“What’s not understood is that love does not conquer all. People like to think of adoption through rose-colored glasses and that because this family loves this child — usually, not always — everything’s going to be OK,” said Young. “Particularly with children of color in trans-racial adoptions, we need more than just love. We need recognition of who we are and where we come from.”

Those struggles with identity are implicit in “Blue Bayou,” beginning with the opening scene, which finds Antonio on a job interview where the manager asks about his ethnic background. For Chon, the static frame instantly introduces Antonio as a Southern man through his accent and his white stepdaughter, both aspects of his life that defy the limited, white-centric view of what an American family is. Chon himself has been subjected to such uncomfortable exchanges.

“When I go to Korea they don’t consider me Korean, they consider me American. Yet when I’m here in the United States, I’m constantly asked that question, ‘Where are you from?’ Nobody ever just automatically assumes that you’re just an American and you’re born and raised here,” he recalled. “They look at your face and they just make assumptions that you’re from somewhere else. I felt that many a time growing up in the United States.”

As a fan of Oscar-winning Swedish actress Alicia Vikander since her debut in the film “Pure,” Chon envisioned her in the part of Kathy. As a Scandinavian playing an American, Chon believed that every one of her choices would be intentional, including her accent. He wrote her an impassioned letter that led to a video meeting. For the actress whose diverse credits include “Tomb Raider,” “Ex Machina” and the recent “The Green Knight,” knowing Chon was seeing her in a different light was refreshing.

“It was interesting because I’ve played British and a royal a few times early in my career, and most people wouldn’t offer me this kind of role. For me it was a beautiful thing that Justin thought I was a very good fit,” said Vikander. “This lower-middle class environment is where I’m from myself. Yes, it’s another country, but in a way it’s probably closer to me than some of the other roles I’ve played in my life.”

Vikander, who as a child attended a school with Swedish classmates of Syrian, Iranian and Croatian origin, was appalled to learn of the adoptee deportations. “It broke my heart to know that so many people have been put in situations where they are deported away from their homes, their families and children,” she said. “I grew up in a country that has quite a lot of refugees, and today there are even more people in need of a new home.”

It’s very difficult for them to find words ... The song is a direct access for them to connect without words.

— Alicia Vikander on the film’s use of music, including the song “Blue Bayou”

Working with a director who was also her co-star made “it even easier to find a language to communicate with,” the actress said. And midway through “Blue Bayou,” she found her favorite scene.

With the looming threat of involuntary removal in his mind, Antonio is invited to a party at Parker’s home almost exclusively attended by her Vietnamese relatives and friends. It’s the first time that he finds himself surrounded by other Asians, even if not precisely from his birthplace. With the crowd’s encouragement, Vikander’s character takes the stage to sing “Blue Bayou,” a track originally sung by Roy Orbison and later Linda Ronstadt.

Though she admits to enjoying karaoke, Vikander is not a trained singer and had never sung on screen, but she understood the profound implications the lyrics had for this couple.

“It’s very difficult for them to find words, and then trying to connect to one another or handle their own anxieties and worries and sorrows,” Vikander explained. “The song is a direct access for them to connect without words.” The event also reaffirms Antonio’s unvoiced yearning to reevaluate his uprooting — a need depicted throughout the film with magical realist underwater sequences that invoke an otherworldly atmosphere.

“It’s a scene where Antonio gets, for the first time, to really open up this door and reflect over another part of him, a heritage. Obviously, his home is in America and he is not defined by the place he was born in, but his mother is from [South Korea],” said Vikander. “And even though you find a new self in a new part of the world, there’s still the curiosity to at least understand or know part of the history that you have, where you come from.”

Young also found a deeply personal connection to that sequence. “The first time that happens for an Asian adoptee is significant. There’s a discomfort, yet there’s also a recognition and a feeling of home at the same time. Justin shows that in how he plays Antonio in that scene,” she said. “All of us adoptees that have gone into the discovery of our Asian identity have the memory of when that happened very present.”

Key to the discovery is the character of Parker, not only because she offers Antonio a community but also because of her buoyancy in spite of her terminal illness. As a result of spending time with her, Antonio is more introspective about his devastating circumstances in relation to someone undergoing something even graver.

“[Parker] was meant to be a mirror to him, and also a motherly figure, a kind of mentor to guide him on his journey,” said Chon. “They’re both reaching a sort of a death, Antonio’s reaching a death as an American and she’s reaching a physical death.”

For Chon, now with four features as a writer-director a decade away from his days as part of the “Twilight” franchise cast, the impetus remains reframing cinema’s still narrow vision of who gets to be an American on screen. And what that means.

“My films have always been consistent in that I’m trying to bring empathy to my community, to Asian Americans. All of them have that in them and they also have diversity, even within one minority group,” he said. “One of my goals in filmmaking is showing how we can coexist in this country and how much we’re more alike than different. That’s what I aim to do in every film.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.