Review: Rebecca Hall keeps the tension building in ‘The Night House’

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health officials.

The scariest moments in “The Night House,” an elegant nerve-jangler about the sometimes lethal cost of waterfront real estate, are marvels of jump-scare engineering. They’re shivery little reminders of what can happen when ominous music, assaultive sound design and serpentine camera moves are flexed to the state-of-the-art max. I’m as weary of cheap jolts as the next horror fan, but the jolts in this movie don’t feel cheap; if anything, they feel curiously plush, even luxuriant. The director, David Bruckner, doesn’t just mindlessly apply the electrodes; even when he jars you to attention, he always seems to be drawing you into something deeper and more atmospheric. He delivers a scare you can sink into.

He also knows that, when you’re entering haunted-house terrain this unabashedly derivative, even a little investment in psychological tension can pay off in a big way. The moments that stay with you in “The Night House” aren’t the scary ones so much as the tense ones, and to see Rebecca Hall in action is to immediately grasp the difference. As Beth, an upstate New York schoolteacher cycling through shock, grief, rage and fear after her husband’s suicide, Hall puts you on edge almost as much as the house in question. She’s a brooding pleasure to watch here; sometimes you fear less for her than for the people unfortunate enough to get in her way.

You suspect that Beth didn’t suffer fools gladly when her husband was alive, and she suffers them even less gladly now. In one juicy early scene she has a meeting at school with a parent, one of those entitled busybodies who’s chosen the worst possible day to try and bump up her kid’s grade. After a few minutes of passive-aggressive negotiation, Beth calmly announces, “My husband shot himself,” taking a cold, mirthless delight in the woman’s shock and shame as the details come spilling out. The exposition is for our benefit too: We learn about the depression Owen (Evan Jonigkeit) apparently battled in private, the gun he apparently purchased in secret and the little boat in which he did the inexplicable deed.

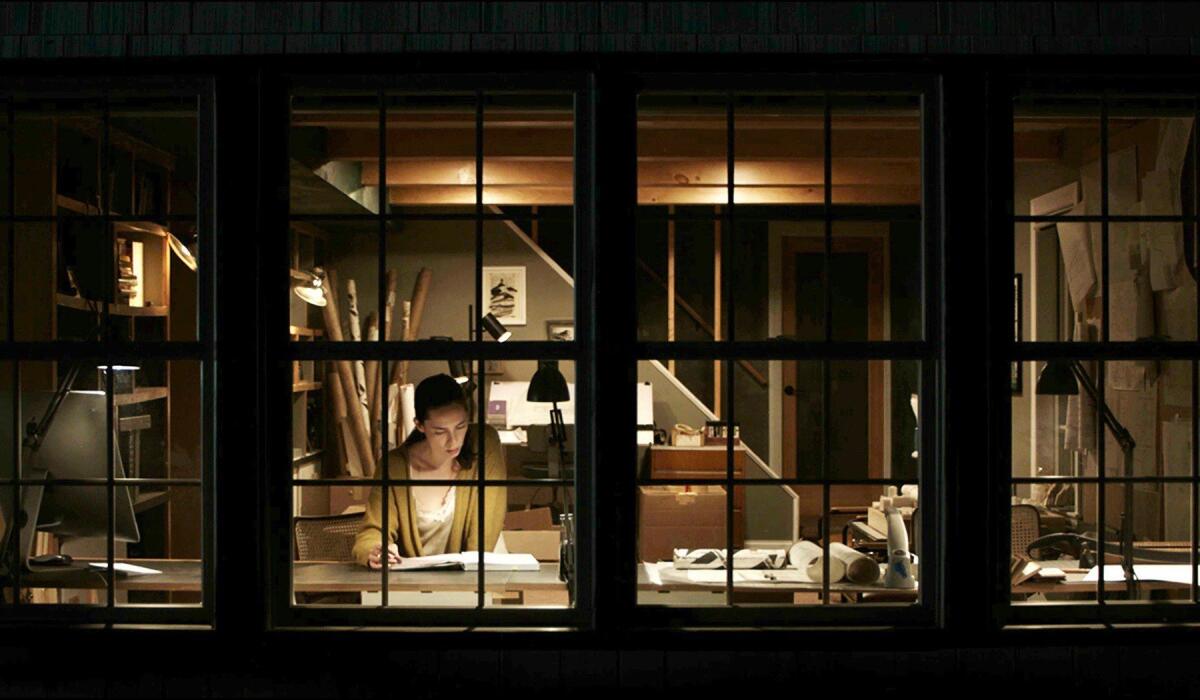

That boat, still tethered to the dock just below their gorgeous lakeside house, is a grim reminder of tragedy. So is the house itself, which Owen, an architect, designed and built over much of their 14-year marriage. Now his restless spirit seems to live on in the very walls of his stylish glass-and-wood creation, manifesting itself in bloody footprints and self-operating audio equipment and also in dark dreams that tear at Beth’s grip on reality. What disturbs her most, though, isn’t what her husband might be up to now; it’s what he was up to in his final days and weeks.

What is Beth meant to conclude from the unsettlingly occultish design sketches she finds among Owen’s things? Or the photo she finds on his phone of a dark-haired woman to whom she bears an unmistakable resemblance? The script, by the duo of Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski (“Super Dark Times”), has fun marinating in these and other possibilities, stranding Beth in a labyrinth that abounds in weird doublings and doppelgängers. And Bruckner, a skilled horror craftsman whose previous films include 2017’s “The Ritual” (and omnibus-style freakouts like “V/H/S” and “The Signal”), treats each new wrinkle in Beth’s investigation with just enough seriousness to entice you along.

The puzzle may ultimately be less than the sum of its intricately ludicrous parts, and its attempts to merge grief and horror — to show them as flipsides of the same emotional coin — pales beside a thematically similar thriller such as “The Babadook.” Still, it’s hard not to appreciate the unique care with which Bruckner and the writers have worked out their story. And it builds to a doozy of a fog-and-mirrors payoff, terrifying and weirdly seductive in equal measure, that seems to be riffing on the Emily Dickinson poem “Because I could not stop for Death.”

Owen, despite or perhaps because of his ambiguities, remains something of a handsome cipher in a movie that keeps leading you back to Beth, into the recesses of a mind with its own long history of dark impulses and buried traumas. Those recesses are something of a sweet spot for Hall, who’s especially good at undercutting her imposing physicality (she towers over most of her co-stars) with a tremulous vulnerability. Here, as in the biographical drama “Christine,” though in a very different emotional register, she shows you a keenly intelligent mind, chafing against social niceties and hovering at the brink of madness.

But the movie isn’t a one-woman show: It’s smart enough to give Beth any number of sharply etched foils, including a concerned neighbor (Vondie Curtis-Hall), a mysterious outsider (Stacy Martin) and, most movingly, a close friend (Sarah Goldberg) who reminds her that she isn’t alone in her turmoil. In these moments, “The Night House,” for all its hellish visions and demonic symbols, emerges as an unusually humane chiller: a movie that delights in pulling the rug out from under you but also cares enough to cushion your fall.

‘The Night House’

Rated: R, for some violence/disturbing images and language including some sexual references

Running time: 1 hour, 48 minutes

Playing: Starts Aug. 20 in general release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.