Are the 2021 Oscars doomed? Or will they prove the movies still have a bright future?

In the run-up to the Academy Awards, Hollywood is normally bursting with excitement. Red carpets are vacuumed. Gowns are fitted. Speeches are nervously practiced in front of mirrors.

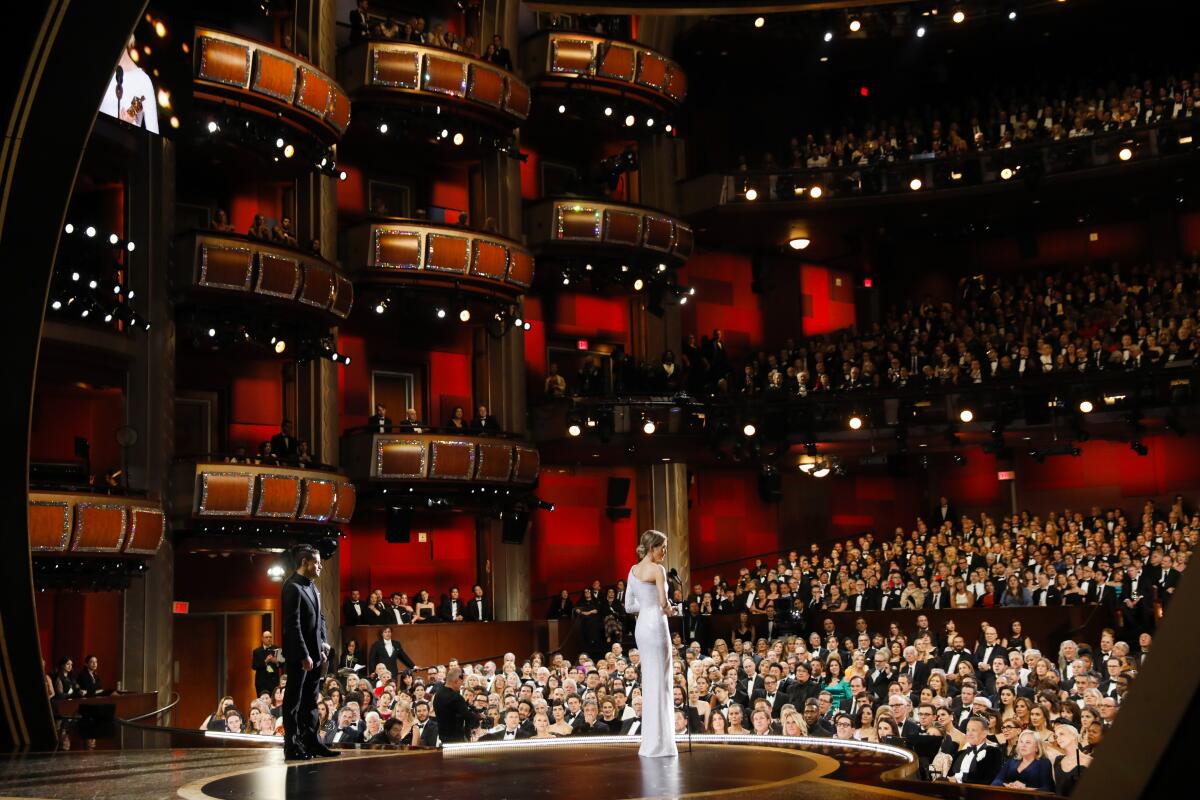

But while much of that preparation has still been happening — the show, after all, must go on — Sunday’s Oscars ceremony is taking place against a backdrop that is far from festive. With the film industry struggling to emerge from a pandemic that has upended business models and decimated balance sheets, the overall mood around town heading into the show, which will be held in person at Union Station, the Dolby Theatre and via numerous satellite hookups around the world, is more one of existential anxiety than razzle-dazzle celebration.

Starkly punctuating this year’s undeniably grim awards season, on April 12, just three days before the Oscars voting period opened, news broke that Los Angeles’ much-loved ArcLight Cinemas theater chain, which includes the iconic Cinerama Dome, was permanently closing, delivering a gut punch to local cinephiles.

Amid this gloom, the planners of this year’s Oscars are not merely looking to honor the current crop of nominees, many of which may be unfamiliar to viewers given that movie theaters have been closed for the last year. They are hoping to give the entire industry a proverbial shot in the arm by reminding people around the globe that movies still matter. The show’s tagline — “Bring Your Movie Love” — carries a whiff of pleading, as if the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences were soliciting prayers for an ailing loved one.

“We do want people to rebuild their relationship with the movies in the sense of going to the movies,” director Steven Soderbergh, who is producing this year’s Oscars telecast along with Stacey Sher and Jesse Collins, told The Times this month. “The communal sensation of watching a movie with 350 strangers — that sense of connective experience is good for us. Everybody involved — the producers, the writers, the presenters — is very sensitive to finding this balance so that we don’t seem like we’re diminishing or downplaying what’s happened since last March. I don’t think that’s possible. But we want the show to be joyful.”

Though last year’s Oscars took place just weeks before the pandemic closed movie theaters, this year’s ceremony comes as vaccines are rolling out and theatrical exhibition is slowly coming back to life, bookending a dismal year that most in Hollywood would be only too happy to put in the rearview mirror.

The pandemic wiped out last year’s key fall film festivals, putting a damper on awards season before it even had a chance to begin. Venice went on with temperature checks, physical distancing, designer masks and a reduced slate of mostly European films, while Telluride was canceled, and Toronto was forced to shift to a mostly virtual event with a fraction of its usual lineup.

Without the normal methods of building buzz through festival screenings, awards campaigners resorted to virtual events, lining up celebrities, filmmakers and prominent journalists to lead discussions with contenders’ casts. The tender Korean-immigrant story “Minari” had premiered before the pandemic at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. But, like most movies, it held dozens of remote screenings for awards season voters, enlisting the likes of Katie Couric, Sandra Oh, Ramy Youssef and Ann Curry to host. A lively one-on-one conversation between Helen Mirren and supporting actress nominee Yuh-Jung Youn drew a huge turnout.

Though many of the virtual events were engaging and well attended, they still took place in a digital void. “We are based on gatherings,” said veteran awards consultant Tony Angellotti. “Making a case for a film in a year without premieres, without rooms full of people, was strange. You have no idea how people are responding.”

Exclusive access and best moments from Hollywood’s most prestigious award show

With the Oscars delayed by two months — in an attempt to expand the pool of contenders and buy time for relaxed COVID-19 restrictions, which seems to have worked — and no widely seen blockbusters among the best picture nominees, the Oscars producers’ biggest challenge may simply be getting people to tune in. Ratings for recent awards shows plummeted to all-time lows, with the viewership for February’s Golden Globes plunging 60% from last year, and the Oscars are widely expected to follow suit.

“Most people don’t know the Oscars are happening,” said J.D. Connor, an associate professor of cinematic arts at USC who’s teaching a course on Netflix this semester. Connor noted that while Netflix has a collection on its landing page spotlighting its Oscar-nominated movies, the streamer doesn’t direct people toward Sunday’s show, this despite the fact that it leads the field in nominations this year with 36. “They like the prestige, but they don’t care if you actually watch the ceremony.”

In the past, Connor said, the Oscars served as something of a ticking clock, spurring occasional moviegoers to go to theaters to see the nominated films. But with studios making fewer prestige movies and streamers stepping into the breach, that dynamic no longer exists. Moving forward, the film academy should adapt to the changing times, he argues, and find a way to honor the sort of long-form limited series programming that is now driving the cultural conversation.

“It’ll be important to give people the sense that the things that they’re passionate about are the things that the Oscars adjudicates,” Connor said.

At the same time, as Hollywood looks ahead to the critical summer movie season and beyond, some early green shoots have poked through the parched ground, giving the industry hope for a return to something close to normal. A number of big-budget crowd-pleasers that had been pushed back last year, like Marvel Studios’ “Black Widow” and the sequels “F9” and “A Quiet Place Part II,” are set to be released in the next three months. There is already a waitlist for passes to September’s Telluride Film Festival, which has added an extra day.

“Check out the numbers of ‘Godzilla vs. Kong,’” said Sher of the recently released Warner Bros. monster mash-up that has grossed $80 million at the domestic box office thus far, a record since the pandemic began, and was simultaneously released on HBO Max. “It’s headed towards $100 million [in the U.S. alone], and that’s with 50% or even 25% capacity in the biggest markets. When you feel safe and are vaccinated and can get back to theaters, I know I’m dying to go back.”

Indeed, some die-hard movie lovers never stopped. “Nomadland” producer Dan Janvey managed to see all but one of the best picture nominees in theaters, including his own film, which he watched with his girlfriend and her mother. They were the only people in the theater. He remembers when “Tenet” landed in newly reopened movie theaters last Labor Day weekend, asking friends, “Will I risk my life to see a Chris Nolan movie?” The answer was yes.

But even for a hardcore cinephile willing to drive an hour or two from Brooklyn to Connecticut and Hoboken, N.J., to see Netflix titles he could easily stream at home, Janvey thinks that the rise in at-home viewing options — which has only accelerated since the pandemic began — doesn’t signal the death of cinema. “Nomadland” rolled out simultaneously in theaters and Hulu after a brief, exclusive run in IMAX locations.

“I think the optionality for people who love movies is a beautiful thing,” Janvey said, “and we saw a level of flexibility with movie culture that had never happened before in our industry. I’m hoping that sense of adventure and weirdness and finding community and finding solitude will continue.”

Shaka King, director and producer of the best picture nominee “Judas and the Black Messiah,” can only describe the ups and downs of the last year as “weird.” His drama about Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton premiered at a virtual Sundance Film Festival before landing, like “Godzilla vs. Kong,” on HBO Max. The digital platform will be the streaming home to all 2021 Warner Bros. movies the same day they hit theaters.

King missed connecting with audiences but took solace in stories of people watching the film repeatedly, gaining new insights with each viewing.

He bristles at the assumption that big-budget event films will dominate multiplexes in the future, consigning indie movies to the margins, or that young audiences are a lost cause.

“Good movies were cool to watch when I was a teenager,” King, 41, says. “That was the culture, growing up in New York. It’s all a matter of whether it’ll be cool to watch good movies in the next five years. And that’s marketing.”

With all these hopes and fears riding on the Oscars, the show’s director, Glenn Weiss — who has helmed five previous Oscars telecasts — knows this year needs to strike a delicate balance.

“Look, I’m very much looking forward to what we’re putting on the air and how we’re doing it,” Weiss said. “I’m also a human being breathing and living this pandemic as well, with a family and people that I care about. We hope we’re out of this, but we don’t know that we’re out of this. So I think the big mission is to continue creating hope. Bringing people together safely and letting folks at home be a part of a celebration that feels more normal is just hopefully part of helping the healing process.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.