How the ending of ‘One Night in Miami’ re-created a long-lost cultural landmark

The following story contains spoilers from the movie “One Night in Miami,” now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

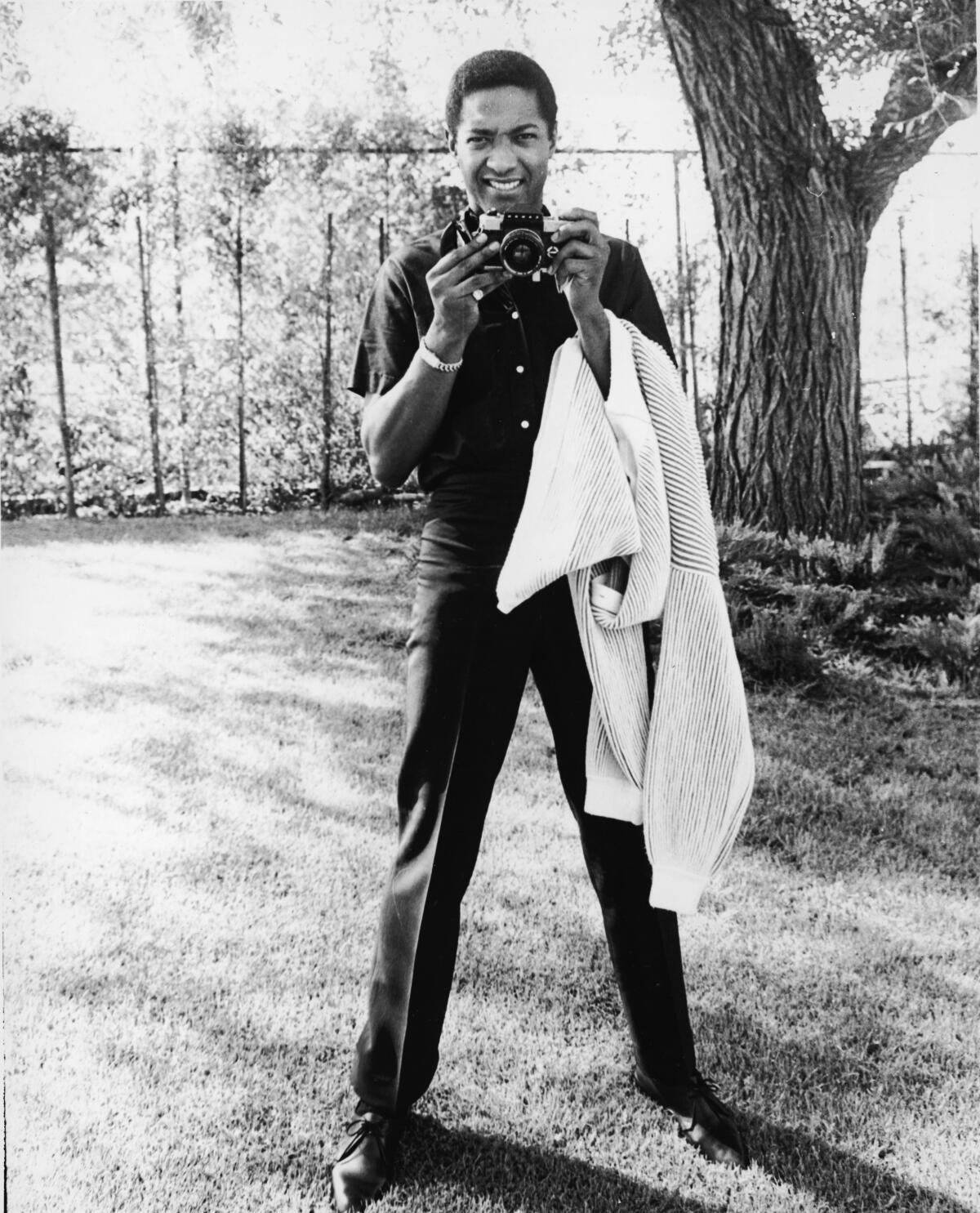

The final moments of Amazon’s “One Night in Miami” drop in on Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.) as he makes an appearance on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.” Unflappable and debonair as always, he’s just finished performing one of his signature feel-good pop songs when he launches into “something that I’ve been working on, something new I haven’t really shared with anyone yet — anyone except for some friends of mine.”

That song, “A Change Is Gonna Come,” would go on to become an anthem of the civil rights movement and, for many, one of the greatest songs of all time. Covered by artists of every stripe, it has also emerged as a mainstay of momentous occasions: President Barack Obama’s first inaugural in 2009, by Bettye LaVette and Jon Bon Jovi; Whitney Houston’s funeral in 2012, by Kim Burrell; last year’s Democratic National Convention, by Jennifer Hudson. “That piece of writing is so powerful,” says Odom. “It means something very special to us, so it’s performed with care.”

“One Night in Miami,” directed by Regina King and adapted by Kemp Powers from his own play, is a fictionalized account of the 1964 night Cooke, Malcolm X and Jim Brown met up with Cassius Clay after the fighter’s prizewinning bout. But the decision to end the movie with a re-creation of this real-life performance — even if it meant fudging the date of Cooke’s “Tonight Show” appearance — was a knowing one: With Odom’s powerful rendition of the singer’s iconic tune, the film ties together not only the experience of its four leads, but also that of its countless listeners in the years since.

Before debuting “A Change,” Cooke had built an impressive career as a crossover artist with easygoing compositions like “You Send Me,” “Wonderful World” and “Cupid.” But something shifted in 1963, when he and his band were turned away from a Louisiana hotel; when he refused to leave, he was then arrested and jailed for disturbing the peace. Meanwhile, Bob Dylan’s protest song “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an undeniable hit.

“This is a white boy from Minnesota who has nothing to gain from writing a song that speaks to the struggles of our people, more to the movement, than anything you have ever penned in your life,” Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) tells Cooke in the movie. “Since you say being vocally in the struggle is bad for business, why has this old song gone higher on the pop charts than anything you got out?”

For Cooke, “A Change” was “a real departure,” “undoubtedly the first time that he addressed social problems in a direct and explicit way,” Cooke’s biographer, Peter Guralnick, told NPR in 2014. “It was less work than any song he’d ever written. It came to him almost whole, despite the fact that in many ways, it’s probably the most complex song that he wrote because it was both singular — in the sense that you started out, ‘I was born by the river’ — but it also told the story both of a generation and of a people.”

Cooke was reluctant to perform the song live, not only because of its ominous tone, but also because the lush, intricate arrangement called for a French horn, three trombones and a 13-piece string section, according to Guralnick’s book “Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke.” But the record label arranged for the additional musicians to accompany him on “The Tonight Show,” his only televised performance of the song. Sadly, footage of the appearance has not survived.

In real life, that “Tonight Show” gig occurred weeks before the foursome’s historic gathering. But the song has always closed out “One Night in Miami,” from its 2013 debut at Los Angeles’ Rogue Machine Theatre to subsequent stagings in Denver, Baltimore and London. In the play, Cooke revisits the topic of Dylan’s hit, telling Brown, “Just because I haven’t put out any records about the movement doesn’t mean I haven’t written any songs about it.” He then shares a portion of the song a cappella for his close friends — and the live audience, which is of course acutely aware of the song’s rich history.

The film adaptation became “a wonderful dual opportunity to present the entire song with its full arrangement, and to re-create a moment that really happened but none of us have ever seen,” says Powers. It was the last scene of the movie that Odom shot, and happened to fall on Feb. 7, the same date of the actual “Tonight Show” appearance 56 years earlier.

“Since there’s no video footage of it, that gave us the confidence to take a little bit of a leap of the imagination and do something that not only honored Sam and the piece that he wrote, but also the story being told in the film,” says Odom, whose performance was fueled by the rigorous conversations he had just filmed. “Sam was never closer to me than he was on that day. Having listened to as much of his music as I had, and given how much he influenced so many of my heroes, I tried my best to do this song justice.”

King had Odom sing “A Change” live for the scene, captured in six or eight takes, and started off a cappella because she wanted the song to grow to an emotional climax. Cooke is visibly transported by the song’s final lines, and the camera lingers as he wipes away a tear and recalibrates to his surroundings — a quiet moment spontaneously captured after King yelled “cut” on set, says Powers.

As Cooke croons, a montage reveals what happened to each of the four leads after that night: Brown quit the NFL while on the set of the movie “The Dirty Dozen”; Clay formally changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and Malcolm X grew increasingly fearful for the safety of his family because of threats from the Nation of Islam. The last frames of the movie show Malcolm, imprisoned in his own room and finished with his autobiography, watching Cooke perform on his TV set. He closes his eyes and exhales, seemingly arriving at a place of peace.

Though both Cooke and Malcolm X would be killed before the end of the following year, Powers considers this quiet conclusion — which was not in his original film script, but added by King — a moment of hope, in which Cooke lives up to Malcolm’s urging to use his gifts in the service of the movement: “You could be the loudest voice of us all.”

By those final frames, “Malcolm is at a place where he knows his end is coming,” says Powers. “He’s able to have a brief moment of relaxation because even though he’s not going to be there, his job is accomplished because his influence will live on, because he was able to inspire something like what Sam just did. A change is still going to come — if not from him directly, then from those who come after him.”

Powers hopes the ending speaks particularly loudly to the movie’s young Black viewers. “Even if all of us can’t make it to the finish line, we can do what we can to propel one another and hold one another up,” he says. “Incredible progress has been made since 1964, and so many of the people responsible for all that progress were quite young. Remember, these four men were in their 20s and 30s. Martin Luther King was 39 when he was assassinated.

“Unfortunately, it seems like people get old and are unwilling to let go of their power in this country,” he continued. “But the reality is, it’s often been the young, who are told they don’t know what they’re doing, who bring about all this change.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.