‘Dick Johnson Is Dead’ will emotionally destroy you. Here’s why you should watch it anyway

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about my dog dying. He’s not sick, and he’s not even particularly old — 8 — plus, Australian shepherds typically live until they’re around 14 or so.

But he sleeps more now, sprawling out across the wood floors to keep cool. Or maybe he’s always slept this much, and I just wasn’t home all day to witness it until the pandemic hit. Still, there are other reminders of his age: The gray hairs in the arch of his eyebrows. The extra few seconds it takes him to rise to his paws. How long he pants after a heated game of fetch.

This summer, one of my roommates was giving him a belly rub when she came across a lump under his fur. The veterinarian would later diagnose the spot as benign, but in the moment when I first brought my hand to his chest and felt the abnormality, tears instantly streamed down my face. I was certain it was cancer, and that I’d have to put him down to spare him from pain.

The dog who had been with me since I was 26 and seen me through such formative years of independence wouldn’t be there for the payoff. I wanted — want — him there when I get married, trotting down the aisle before me to greet my husband, who will heartily scratch him behind the ears. I want him to have his own yard to frolic in, one we don’t share with neighbors. I want him to see so much more of the world with me, when the world, hopefully, expands again beyond our front door.

I know that this anticipatory grief doesn’t serve me — or frankly, him. But how can you love a being so much and not be conscious of the fact that your relationship has an expiration date? Is it possible to ignore the looming threat of mortality — or, ideally, accept it — and strengthen your bond instead?

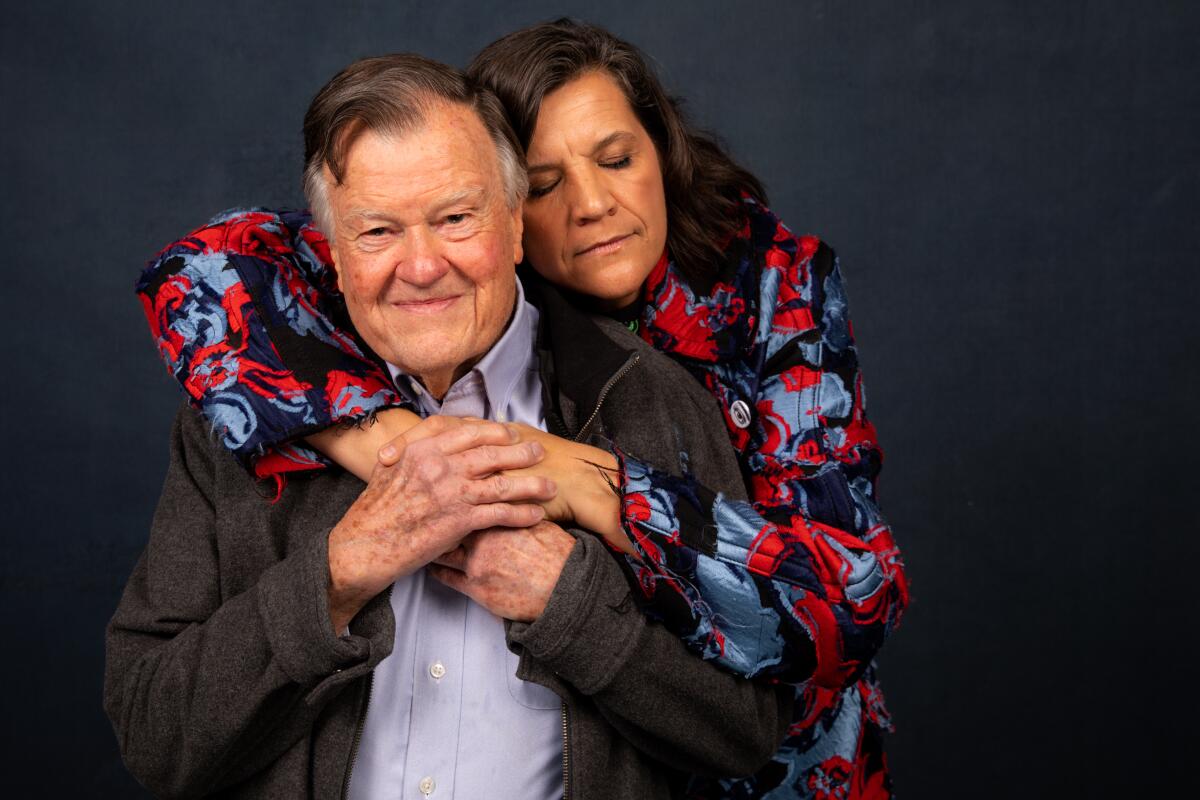

These are some of the questions that Kirsten Johnson wrestles with in “Dick Johnson Is Dead,” the documentary she made about her father. The film, which debuted to strong acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival in January, was released Friday on Netflix. The story begins in 2017, when Kirsten’s dad, Dick, has just been diagnosed with dementia. At that point, Kirsten’s already lost her mother to Alzheimer’s disease, so she knows what the future holds for her father. She knows she’ll have to tell him that he can no longer drive, or live alone in their family’s home in the Washington forest. She knows he’ll have to retire from his psychology practice, packing up his office in a downtown Seattle high-rise. And she knows that he’ll lose his capacity to listen, unable to give her the advice she’s long treasured.

So Kirsten came up with an insane idea, and pitched it to her dad: “I want to make a movie where we kill you, over and over, using stunt people. Until you die for real. So we’ll just never stop making this.”

Dick laughed, and then said he was game. This was, after all, the man who had introduced his daughter to Monty Python and “Harold and Maude” and “Young Frankenstein.” Sure, pretending to bleed out after tumbling down the staircase or getting clobbered by a falling air conditioning unit was, uh, macabre, to say the least. But it would allow him to spend more time with Kirsten, which was really all he wanted.

For Kirsten, the “existential experiment” held even more weight. It was an act of defiance.

“Screw death, man!” she said. “I really do think cinema is time travel. When we’re watching people we love through movies, they’re alive for us. So I was like: ‘Can I ask cinema to keep my father alive forever?’ I was going to use every capacity I had to try to figure out what we could do to change this reality.”

She knew, of course, that this quest for literal immortality was futile. She really knew it last Sunday, when she FaceTimed me from her brother’s house in Washington, D.C. Kirsten had traveled there from her home in New York City to visit her dad at a care facility in Bethesda, Md. Yes — major spoiler alert — Dick Johnson is not dead. But at 88, he is very ill. After spending three years living in Kirsten’s one-bedroom apartment, he began walking out the door in the middle of the night. She and her brother had the difficult realization that Dick needed 24-hour-a-day care, and moved him into the home for the elderly in July.

When I spoke to Kirsten, she had just visited him at his new place for the first time because of COVID-19. It was a difficult day. When she left the facility, Dick stood at the window, pleading: “Can you take me with you?”

“I always said that I wanted to accompany my dad until he falls off the cliff of life,” she said. “When we moved him to the home and he was like, ‘Please come get me,’ it was like he fell off the cliff, fell five feet, and was hanging there saying ‘Please, help me up.’ I was like, ‘I can’t.’ So that was super brutal.”

“On the Rocks,” “The Glorias,” “Dick Johnson Is Dead,” ’The Forty-Year-Old Version” and more.

When it comes to thinking about her own mortality, Kirsten, 54, has never been particularly fearful. Throughout her career as a cinematographer — she’s worked on over 50 documentaries, including “Citizenfour,” “The Invisible War” and “Fahrenheit 9/11” — she has developed a reputation as a risk taker. In Taipei, one of 86 countries where she’s wielded a camera, she once had to film from one of the tallest buildings in the world. On the 99th floor, the engineer asked if anyone was willing to climb the staircase with him to the 101st level; she didn’t even hesitate.

“I’m not as aware of what might happen to me as perhaps some other people are,” she said. “It’s not that I’m fearless, but I’m deeply interested.”

In her personal life, Kirsten has also leaned into uncertainty. When her mother died, she was 41, and the loss crystalized her desire to have children of her own. She was dating a man who didn’t want kids, so she broke up with him and “started to do the classic thing of, like, I’m going to find someone else to have children with in half an hour.” While she was searching for a partner — and mulling her fertility options — she attended a Sundance event in New York City. At the party, she was introduced to filmmaker Ira Sachs (“Love Is Strange,” “Little Men”) and learned that he and his husband, Boris Torres, also wanted to have a child.

The next day, they all met and decided to try to have a baby together. By then, however, Kirsten was nearly 44, and her doctor informed her that getting pregnant with her own eggs wasn’t likely. So she, Sachs and Torres agreed to use an egg donor, and Kirsten soon gave birth to twins. After Viva and Felix arrived, an apartment opened up right next door to Sachs and Torres, and Kirsten moved in. The twins, now 8 years old, have a room in each place in the lower Fifth Avenue building.

“I remember being terrified before doing this,” Kirsten recalled. “It wasn’t the way my life was supposed to work out. I was going to be married and have children. But I just remember really consciously being, like, fear or love — what’s the choice? And I had the same experience when it dawned on me that I was in love with Tabitha.”

Tabitha is Tabitha Jackson, a film producer who this year was named the first female director of the Sundance Film Festival. Kirsten had never been in love with a woman before meeting Jackson, whom she wed in Utah on the opening day of Sundance this year. It was her father, she said, who accepted the relationship before she was even fully able to herself.

“When I was struggling with ‘I can’t believe I fell in love with Tabitha. Who am I now?,’ he didn’t miss a beat,” she said. “He was like, ‘I’m so thrilled that you have someone wonderful who loves you.’ I couldn’t even do that in relation to my own self.”

Dick’s love for his daughter is unassailable. When she called him on speakerphone — which she agreed to do so I could ask him a few questions — his affection for her was so palpable I had to grit my teeth to stop from crying.

He told me he had a wonderful time being in the documentary, and didn’t mind faking his own death. “It was fine! No problem at all!”

“My daughter is a very accomplished filmmaker. I trust her explicitly with my life,” he said, and I could hear him smiling. “I’m actually honored by it. And it doesn’t bother me a bit. It’s really an honor to be filmed by you, sweetie.”

There’s one scene in the movie where Kirsten literally stages her father’s funeral, and she calls on dozens of his friends to show up at a church and deliver eulogies. Dick watches from the back, listening as those closest to him express their love.

On the phone, Kirsten asked her dad if he thought the funeral attendees were aware he had dementia.

“Oh, very possibly so,” he replied. “I think most people forgive me a lot for that.”

“They totally forgive you,” she said. “You don’t have to be forgiven. You didn’t do anything to cause the dementia.”

“Would you forgive me, sweetie?” he asked.

“I do forgive you. Although sometimes, I’m just mad at the dementia. I’ll never be mad at you, but I’m mad at the dementia. And you don’t need to ask for forgiveness.”

They continued to talk, and Dick asked a few times when Kirsten would be coming to visit him again. He kept saying how anxious he was to see her. She assured him that she would be returning the following day.

“Tomorrow?” Dick said. “OK, super. I will live for tomorrow. I love you dearly!”

After Dick hung up, I asked Kirsten how she thinks she’ll feel when her dad finally does die. She said she’s tired of the dementia — tired of him not being able to live the way he wants to. So, in many ways, his passing will come as a relief.

“It will also be a total devastation,” she added. “And I will do anything to stop it from happening. Both of those things are true.”

Suddenly, I found myself telling her about my dog. (His name is Riggins, by the way.) I wanted to know if there was something she’d learned during this process that has made her feel better about death. She has confronted her father’s mortality head-on. Should we all be doing the same? Talking to those we love most about the fact that living without them is incomprehensible?

Filming her dad, she said, really did make her feel better. She felt like she got to extend the good moments — keep them alive longer. Introducing a camera into their relationship was catalytic, she said. It also allowed her more time with him during his final years, a way to make money that didn’t require her to travel far from home.

“I needed the movie to help me cope with this,” she said. “How devastating it is to be human. To love is to have to experience this wrenching, horrible thing. But when you pick up your dog tonight and pet him and give him an extra snack — you’re going to value him. Acknowledging some of this stuff allows you to embrace pleasure. Because what else are you going to do, cry all the time?”

She asked me to tilt my computer toward Riggins so that she could see him. She called him “a sweetie” and said she was happy that I loved my dog so much.

“Start making a movie with him and you’re going to feel a lot better,” she suggested. “What if you had a film of all of your most favorite things the dog does? You can’t predict how certain things are going to wreck you. It may be that your dog dies right after you’ve fallen in love with someone, and the transition will feel OK. Maybe not. But who knows?”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.