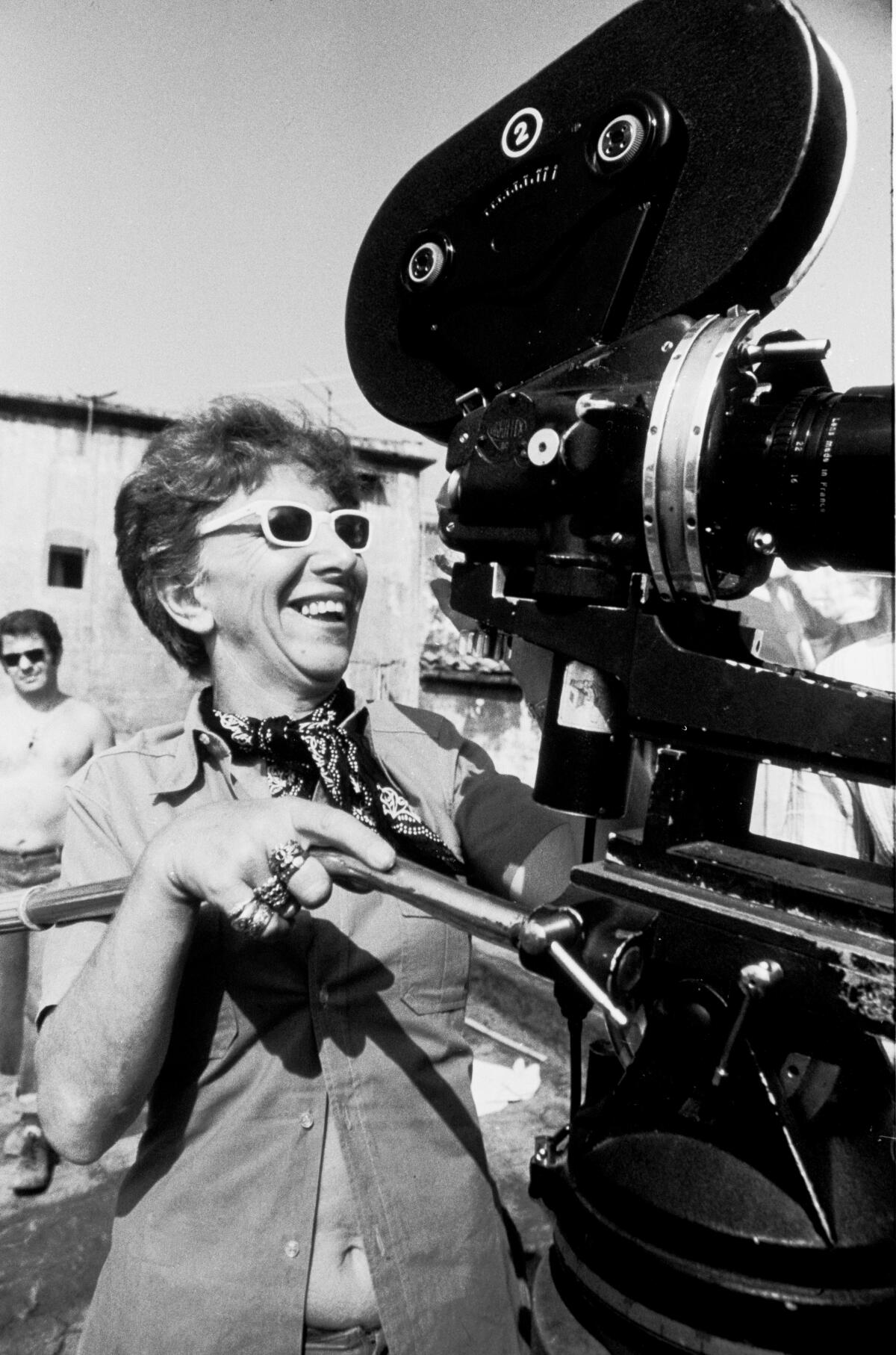

Lina Wertmüller, first female directing nominee, will finally get her Oscar at 91

Italian filmmaker Lina Wertmüller hardly remembers making history as the first Oscar-nominated female director for her work on the 1970s film “Seven Beauties.” But she does proudly recall trolling the ceremony by swapping seats with the wife of a famous Italian movie critic when her name was announced — much to the confusion of the reaction-camera operator.

“She’s always joking in her life,” said Wertmüller’s daughter, Maria Zulima Job, speaking partially through an Italian translator in an interview Thursday with The Times in Los Angeles. “She was always like that.”

The 91-year-old rule-breaker didn’t win the golden statuette then, but 42 years later, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will bestow an honorary Oscar upon her at Sunday’s Governors Awards. The significance of her historic directing nomination wasn’t lost on her at the time — and she looks back at it now with deep pride.

“It certainly was very beautiful,” she said of her first Oscars experience, speaking through her daughter and translator Silvia Bizio. “It was very emotional.”

“Seven Beauties,” a Holocaust period piece starring Wertmüller’s longtime muse, Giancarlo Giannini, was just one of several films she helmed throughout the 1970s that earned her international acclaim and prompted some to hail her as the next Federico Fellini. After all, she’d worked with the Italian icon earlier in her career on 1963’s “8 1/2.”

Two more Giannini pics, the beloved Italian mobster comedy “The Seduction of Mimi” and the pre-World War II caper “Love and Anarchy,” competed for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. “Seven Beauties” also nabbed Oscar nominations for actor, screenplay and foreign film.

But the movie industry is nothing if not fickle, and even the first Oscar-nominated female filmmaker wasn’t immune to its fleeting fortunes. After her ’70s golden age, critics and awards officials, for reasons that remain “a mystery” to Wertmüller, largely turned their backs to her later works — though, like Wertmüller herself, some projects, such as 1999’s “Ferdinando and Carolina,” have earned delayed admiration.

Though Wertmüller doesn’t “know what took so long” for the academy to crown her, the Governors Awards will mark a satisfying culmination of a long life’s worth of contributions to the motion picture industry. And while she may be slightly less energized than her younger self, the visionary clearly hasn’t lost her director’s touch, hitting all of her angles with ease during the photo shoot and often commanding control of the interview by asking her own questions.

Behind her trademark white-rimmed specs, her eyes frequently zeroed in on unfamiliar figures in the room as she evaluated hands, nails and especially body shapes — which, she explained, have always captivated her as a filmmaker.

An often misunderstood auteur, Wertmüller is no stranger to skepticism. Even films such as “Seven Beauties,” now widely celebrated as her magnum opus, once sparked disdain for their blunt and graphic approaches to taboo topics, such as war, prostitution and fascism. Stir in her signature dashes of comedy and satire, and the classic Wertmüller film is a textbook recipe for controversy — a recipe that mirrors those of more recent films, such as this year’s festival darling “Jojo Rabbit,” which have launched similar debates about mixing tragedy and humor.

“When you have something like Nazis that has been around for a long time, you can either talk about it or not talk at all about it,” she said of how she chooses to handle dark subject matter. “I feel it’s better to talk about it and face it without hitting you over the head with it.”

Her nonconformist nature has emboldened others in the past to make the mistake of challenging her vision — at their own risk. Wertmüller has always stood by her artistic decisions. And she wouldn’t have created her art any differently.

“Because I have been able to be myself, I’ve been able to make the kind of films that I did,” she said. “When this could happen, and somebody didn’t want to support one of [my] ideas, I would move on and go to another producer or go find another way to make the film.”

That unflinching ambition eventually led Wertmüller to shatter the academy’s glass ceiling. But even as more conversations about sexism in the directing field are being had, not much has improved in terms of recognition for female filmmakers more than four decades later. Since 1977, just four more — Jane Campion, Sofia Coppola, Kathryn Bigelow and Greta Gerwig — have breached the male-dominated Oscar category, earning nominations in that category. Bigelow is the only woman to have won the Oscar for directing.

But Wertmüller sees promise in the creations of modern-day trailblazers such as Patty Jenkins, who directed “Wonder Woman,” or Gerwig, who scored a nomination in 2018 for “Lady Bird” and is getting strong buzz for her new version of “Little Women.” She’s “confident” more female auteurs will continue to emerge, and she’s always happy to welcome newcomers to the resistance.

“Things change and evolve all the time,” she said. “In the last few years, women have been doing more, it’s true. They have rebelled.”

Though Wertmüller has almost exclusively worked in the Italian film industry, she contends the experiences of women striving to break the mold are universal and that all must overcome setbacks, in America, Europe and beyond.

“Everybody conquers the space that they manage to conquer,” she said. “I don’t see much of a difference between Europe and America.”

Her advice for women still fighting to conquer their space is simple: “Make good movies. And also, of course, have fun while making them.”

With her 2019 award, Wertmüller will become the third woman to receive an Oscar for her work as a director, following Bigelow’s historic win in 2010 for “The Hurt Locker” and French New Wave pioneer Agnès Varda’s honorary Oscar in 2017. “Lots of people” from Wertmüller’s life will attend the ceremony to celebrate her illustrious career, including Job and boyfriend Alessandro Santoni, the Italian consulate general, and Antonio Petruzzi, star of Wertmüller’s debut film, “The Basilisks.”

One critical influence in the director’s circle who will not be in attendance is her late husband, production designer Enrico Job, “who has always been very close and present” in her work and would have been “very, very happy” to see her recognized for it on the most prestigious stage.

“Knowing her, he probably would be happier than she is,” their daughter quipped.

The Governors Awards will serve as part of an extended weekend of Wertmüller festivities, including screenings of the documentary “Behind the White Glasses” and a remastering of her masterpiece, “Seven Beauties,” retouched by Genoma Films. On Monday, Wertmüller will receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

“I’m very proud and grateful,” she said of the accolades.

“She deserves all of it,” Job said, beaming at her mother.

While Wertmüller said she hasn’t plotted any pranks to rival that of her first Oscars outing, her sense of humor is always evident. True to form, she was quick to meet her daughter’s praise with edgy sarcasm.

“It’s my daughter, of course,” she quipped. “If she said something different, I would hit her.”

“She’s joking!” Bizio added promptly. Wertmüller and Job just laughed.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.