In a nondescript Culver City warehouse, members of the metal band Avenged Sevenfold wear protective booties over their shoes to avoid scuffing the floor-to-ceiling green screen. The surroundings couldn’t be more different from their usual fire-and-brimstone aesthetics.

That will soon change, of course, with the green screen swapped out for a series of fantastical concert venues, leaving the platinum-selling quintet to perform beneath lightning strikes, floating monoliths and the massive winged skull, or Deathbat, that has served as their mascot for years.

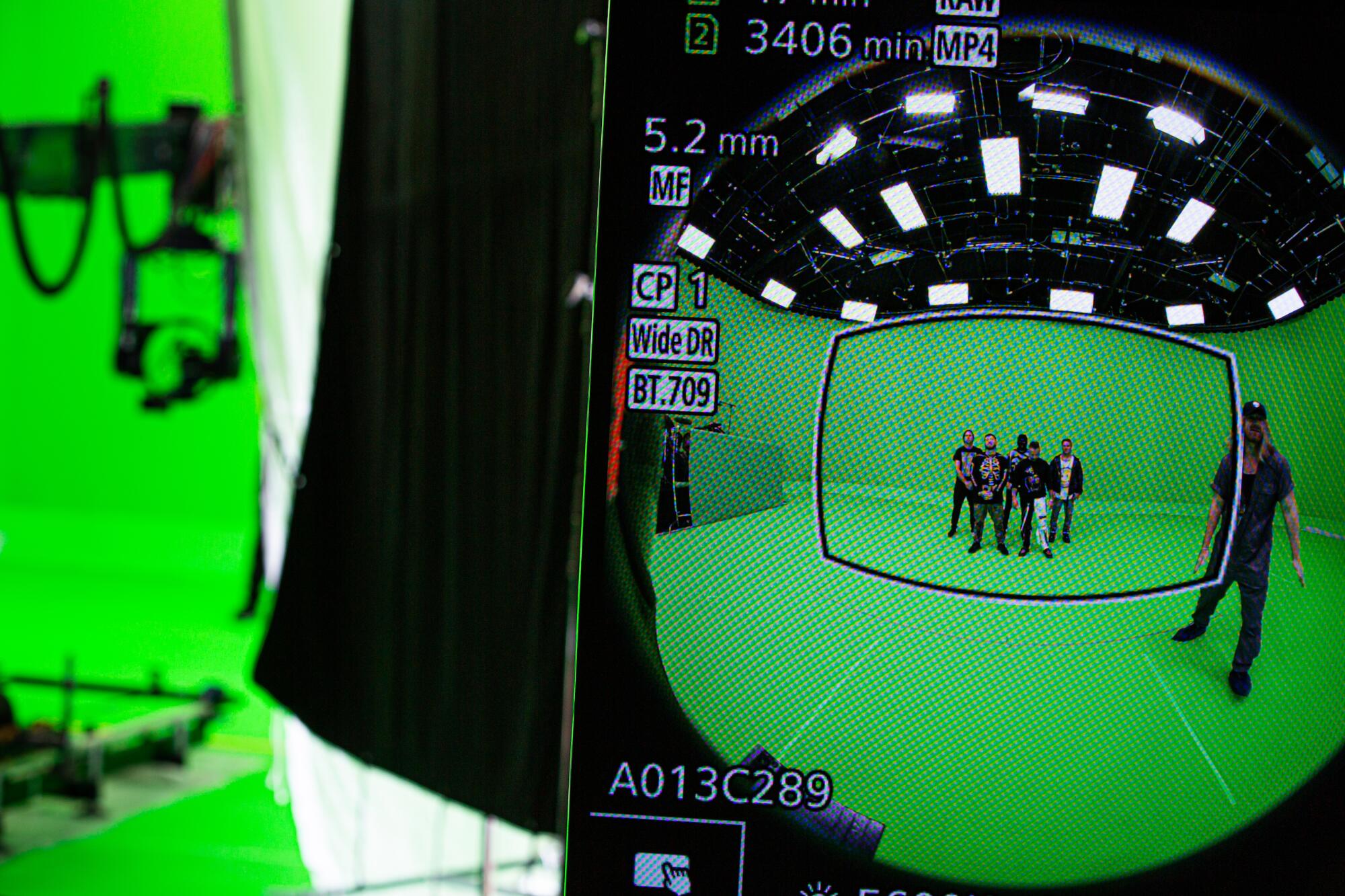

But it will take time for the technologists at tech startup AmazeVR to weave all that dark imagery together. On this Thursday afternoon in early September, the Huntington Beach-born band isn’t even playing full songs yet, just practicing choreography and making sure the members can hit their marks as a crane-mounted stereoscopic camera swoops to and fro.

It’s all in service of creating a virtual reality experience that, when it finally launches early next year, will resemble a cross between a music video, live concert and first-person video game. Developed by Miracle Mile-based AmazeVR, which has previously worked with artists such as T-Pain and Megan Thee Stallion, Avenged Sevenfold’s showcase will allow viewers to don ski goggle-like VR headsets and revisit the performance from the comfort of their couch.

The price has not yet been set, but one song will be available for free. Previous shows launched at $6.99 for a year of access.

AmazeVR aims to bring the energy and showmanship of live events to the virtual reality sector, which has seen substantial investment on the hardware side — major players including Meta and Sony have launched headsets — even as some observers have noted a relative dearth of things to watch and do. The high prices of the headsets have also capped VR’s potential audience, at least for now.

But the impending launch of Apple’s Vision Pro headset is expected to kick off renewed interest in the sector. Apple has tried to frame the Vision Pro as a consumer entertainment device in part, with Disney+ integration featuring prominently in early marketing.

VR concert experiences are arriving at a pivotal time for the music industry. In the wake of an industrywide COVID hiatus and amid ongoing questions about the viability of the streaming model, it’s more important than ever that artists diversify their revenue streams and find new ways to reach fans. Other acts are experimenting with synchronized livestreams and shows within video games.

Flesh-and-blood tours remain big business, but even they are evolving. Taylor Swift and Beyoncé both launched massive tours this year, then spun them off into popular films for movie theaters. Out in the Mojave Desert, U2 is putting on an extravaganza of sight and sound in the Las Vegas Sphere venue — itself a sort of large-scale virtual reality headset.

Avenged Sevenfold frontman M. Shadows sees VR music experiences as one more way to reach fans, including those who might not otherwise attend a live concert, while also letting the band experiment with stagecraft and art direction that they couldn’t pull off in real life.

Skeptics might question whether digital media could ever compete with the flesh-and-blood thrills of a live music experience: the adrenaline of a mosh pit, the euphoria of a stadiumwide sing-along.

But for the singer, it’s a way to make music more accessible.

“There’s always a barrier between the audience and us,” Shadows told The Times during his rehearsal. (The warehouse is owned by Times sister company NantStudios). “You want to make sure that, though there’s going to be a lot of cool stuff going on, the people can get really close to you … and see you sing and see the drums.”

Wearing a Primus T-shirt and a hat repping a line of monkey-themed crypto tokens, Shadows described Avenged Sevenfold as “tech-forward.” The band has dabbled in crypto, collaborated with the Call of Duty gaming franchise and recently teased a Fortnite tie-in.

But Shadows doesn’t envision VR fully supplanting live music. The band tours regularly, and played Inglewood’s Kia Forum earlier this year.

“When you go play a show,” he said, “there’s something about that that can never be replaced. So it’s about fully stepping into what the tech does well, and then fully stepping into what the live show does well.”

When The Times recently previewed an early version of AmazeVR’s Avenged Sevenfold show, the experience combined elements of a live event, a music video and a game. The viewers’ position was fixed to that of the camera, occupying what would’ve been the best seats in the house at a real-life venue, but they could turn their head and look at different parts of the performance.

There was no crowd — a pro or a con, depending on whom you ask.

This software is “democratizing intimate concert experiences that were previously not accessible to all,” AmazeVR CEO Steve Lee said in a statement. “Consumers are not just listening to music; they’re there.”

The experience is not directly analogous to a concert or music video, Lee added, but a new type of media altogether. And it’s not only digital: AmazeVR has previously held in-person events where people watched one of the company’s VR concerts together in a theater.

Some experts see a clear upside.

“While nothing trumps face-to-face entertainment done well, the obvious advantage of virtual concerts is that everyone gets to go, everyone gets to have the best seat, and there is no traffic getting out of the parking lot,” said Jeremy Bailenson, founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, in an email.

Pointing to U2’s show at the Vegas Sphere, he added: “When artists craft carefully immersive visuals to augment their music the results can be spectacular.”

Others are more skeptical.

Virtual reality is “a product still seeking an audience,” said Amy Webb, chief executive of the Future Today Institute consulting firm.

“There are all of these ways that we’re trying to bridge virtual [with] community experiences,” Webb said. “But you still have to ask the question: does this make a significant enough change in my experience that I’m willing to sacrifice everything else for it?”

For example, having a shared experience with others.

But she didn’t write off musical VR media entirely. An immersive display of synced visuals and music, she said — kind of like a trippy, ambient music video — could be more appealing that a simulated live event.

AmazeVR told The Times it raised a $20-million Series B round last year, for about $50 million in total funding since it was founded in 2015. Fast Company named the firm one of this year’s 10 most innovative live event companies.

Even M. Shadows, the Avenged Sevenfold frontman, isn’t sure how things will shake out.

The future of music is “a mish-mash of things,” said Shadows, including concerts, livestreams and Fortnite shows. Some of those experiments will succeed and others won’t, he said, but “it’s gonna take artists that want to take some risks and … try some things.”

“Is AmazeVR the place you want to go where you’re just having a beer on Saturday night and … you want to jump into something you wouldn’t actually go out of your way to drive there and do?” he asked. “I think that’s interesting. I just am not willing to say that it’s been cracked yet. ... But I think these things are fun. It’s fun for us; it’s fun to explore.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.