Bennett LeBarre was in a rush.

He had been brought on to a David Duchovny project as the line producer and needed a production accountant quickly.

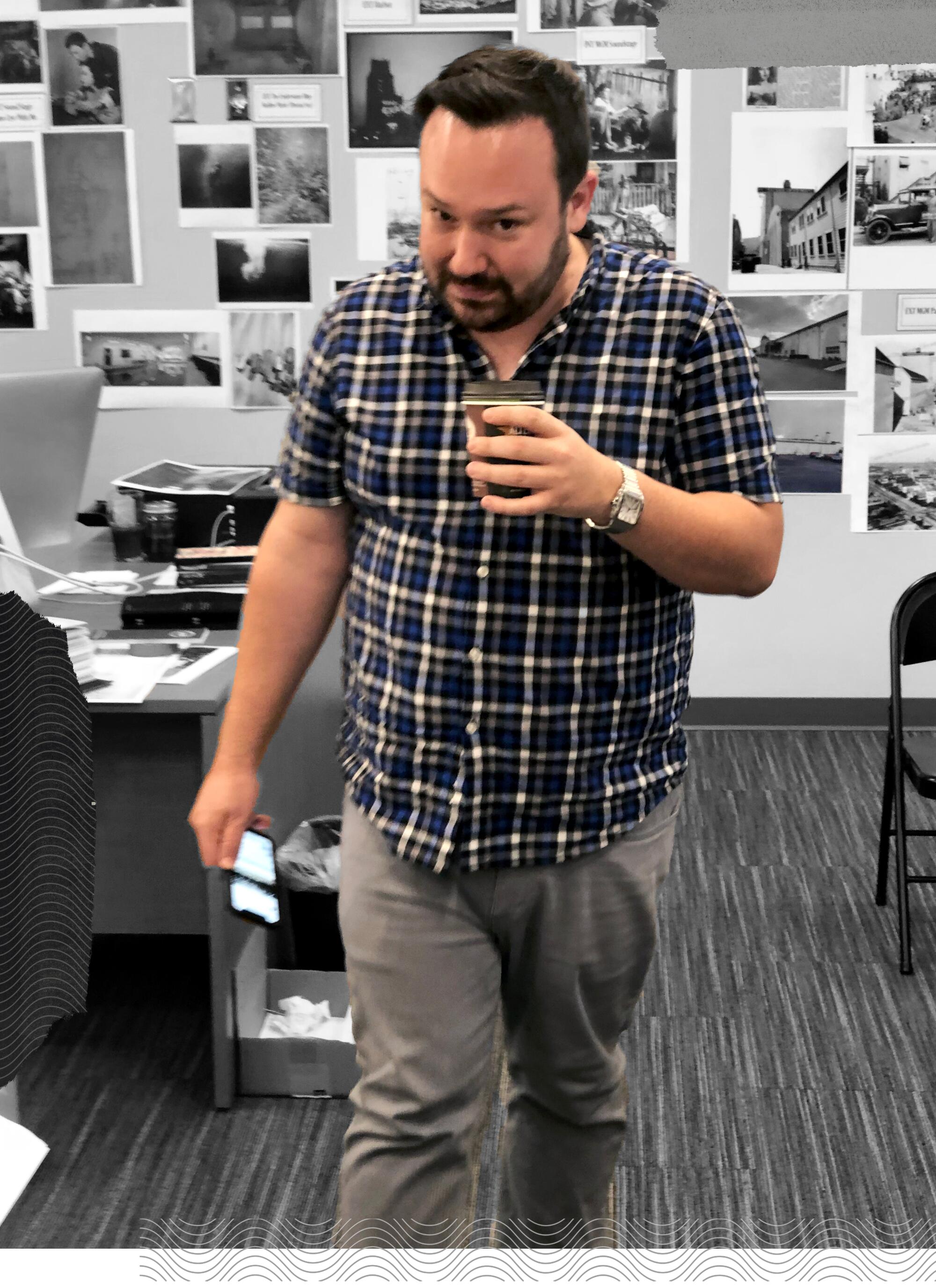

In August 2022, he hired David Brown, who had reached out to him on previous projects. Brown, charming and confident, understood budgets, cash flow and union protocols, according to LeBarre.

LeBarre thought everything had gone smoothly after shooting wrapped for the film, “Bucky F*cking Dent,” about a son who fakes a Boston Red Sox winning streak for his ill father. Soon after, however, he began receiving complaints about crew and background actors not being paid.

The production, it turned out, was over budget, and hundreds of thousands of dollars had been “stolen” by Brown, according to a lawsuit filmmakers filed against Brown in Los Angeles last month.

“He truly sets the house on fire and walks away,” LeBarre said.

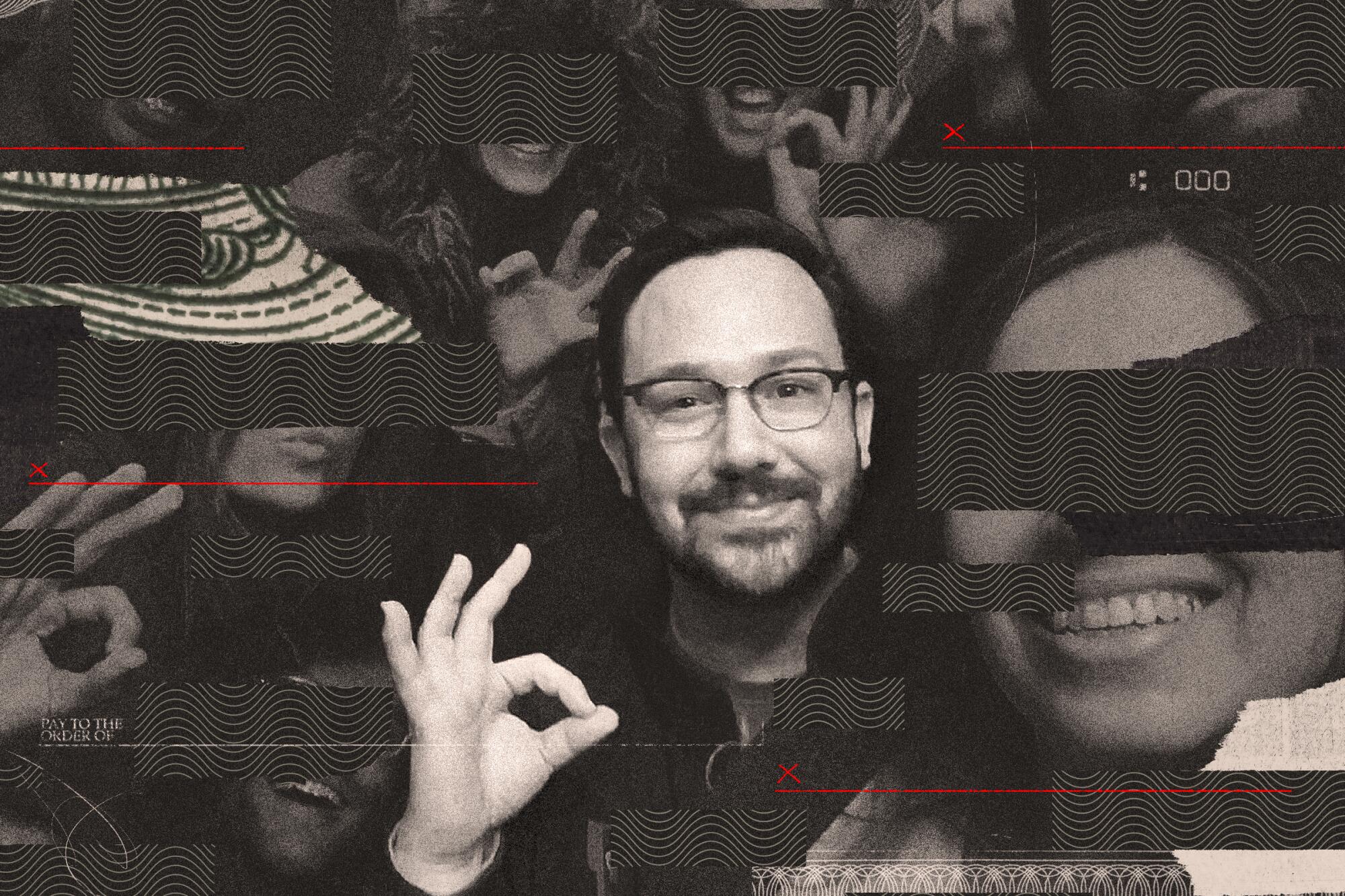

Over the last 14 years, Brown has faced repeated accusations of fraud and deceit that allegedly occurred in many of the productions he has worked on as accountant and producer, according to a review of court records and more than 30 interviews.

In a series of at least 10 lawsuits, two bankruptcy proceedings and two criminal cases in the last decade and a half, Brown and the companies he controls have been accused of forging Kevin Spacey’s signature, skimming hundreds of thousands of dollars off the top of at least two productions, failing to pay crews and background actors and failing to pay back million-dollar loans he took out for projects.

In three of nine lawsuits alleging fraud by Brown, judges in Los Angeles and Tennessee have ordered the producer and his businesses to pay about $5 million.

In two of those cases, Brown and his companies have not paid back most of the money they owe, totaling nearly $4.75 million, said attorneys who sued him.

Brown said he had settled one of the cases amicably, though an attorney representing investors said he and his companies still owe his clients more than $3 million.

In the second case, Ed McPherson, a lawyer for the company Red Card LLC, says Brown owes the company more than $1.5 million.

“We are absolutely astonished that this man has promised to pay our client a very specific amount, at a very specific time, in a very specific manner, and has, once again, reneged completely,” McPherson said.

A Los Angeles County Superior Court judge ordered Brown’s companies to pay $1.36 million on Aug. 31, but McPherson said that amount is now more than $1.5 million including interest.

Other cases have been settled confidentially for undisclosed amounts or were taken to arbitration, and some remain open. None of the 10 cases has been dismissed by a judge in Brown’s favor.

Brown is a small player in the niche world of independent filmmaking. He’s produced and helped finance several low-budget movies — those that cost less than $10 million to make — while working as a production accountant, handling payroll and overseeing cash flow on projects.

His best-known movie is film festival darling “The Fallout,” which he helped produce, starring Jenna Ortega as a teenager who survives a school shooting. The film won the narrative feature competition at South by Southwest, burnishing Brown’s resume.

While he admits making mistakes, Brown denies all the claims that have been made against him, chalking some up to misunderstandings. He blames most of his legal issues on an ex-boyfriend who died last year, though others dispute that.

“I had to work really hard to get where I am today,” he wrote in an email. “I had to overcome a lot. I had to fight for my place. ... I’m not some bad guy.”

Hollywood has long been a magnet for claims of fabrication such as those made by Brown’s accusers. His story is emblematic of the hurried, run-and-gun world of low-budget films and aspiring filmmakers, in which a man who says he can fund a film is often taken at face value by doe-eyed Hollywood aspirants. Even among ambitious producers, though, it is unusual for someone with a history of allegations of financial misconduct to be associated with multiple projects.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Brown, 37, has a deep knowledge of the film industry and loves to discuss movies but can be flighty and hard to reach when problems arise, LeBarre said.

“His favorite line is: ‘Tomorrow,’” he said.

Brown lives in a one-story house in Sherman Oaks with his husband, who has posted photos of the two flying in private jets with their twin babies. They drive Teslas and Mercedes-Benzes, colleagues said.

“They enjoy a lavish lifestyle that includes travel on private jets, luxury homes in New York and California,” said attorneys for 8th Wonder Pictures LLC in a lawsuit. 8th Wonder Pictures sued Brown in 2021 after lending him $3 million for a film and never getting it back, according to the suit. A judge ordered Brown’s company to pay 8th Wonder Pictures $3.25 million in February.

Brown said that “we didn’t see the revenues we had hoped” for because of theater closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

His production company, Clear Horizon Entertainment, focuses on “first-time writer/director projects that would otherwise never be made,” according to the company’s now-defunct website.

But people who have worked with Brown tell a different story.

“He’s a con artist and knows he can take advantage of [first-time filmmakers],” said Chris McGowan, a director who made Anne Heche‘s final movie, “Chasing Nightmares,” with Brown. “Chasing Nightmares” was in postproduction in 2020 but has since become tied up in litigation between Brown and investors over claims of fraud and stolen money. So has a second film Brown produced of McGowan’s called “Flesh.”

Brown said he was “sorry” to hear McGowan called him a “con artist.”

“I’ve made not one, but two movies for Chris to write and direct,” he said. “I gave Chris the chance to make his dreams come true. It’s up to him to use these opportunities to further his career.”

Brown said McGowan owes him thousands of dollars on the films, which McGowan says is untrue.

Brown was born in Tennessee to teen parents in 1986. He was named David Addison Brown, after the Bruce Willis character David Addison from the TV show “Moonlighting,” according to a draft of a memoir he shared with The Times. A gay child who suffered physical and sexual abuse from an early age, Brown found solace in movies and hoped to escape to Los Angeles to try his hand in the industry, he wrote.

He moved to Los Angeles in 2007 to live with a man he met on Facebook while he was in college at Middle Tennessee State University, his memoir states. The man helped him get his start as a production assistant, but the relationship soured and Brown was arrested in 2010 in Massachusetts when the partner accused Brown of stealing his credit card, the memoir says.

Joshua Chelmo, who was with Brown in Boston as a production assistant, said Brown was trying to produce a film called “Dorchester Avenue,” which Brown said Mark Wahlberg was attached to. They were staying with other crew at the Liberty Hotel while scouting locations. Chelmo and others were not being paid their salaries, and Brown even asked him to spot the crew for dinner, Chelmo said.

The ex-fiance of reality star Lala Kent faces the collapse of his company amid a trail of lawsuits, civil fraud charges and allegations of abusive behavior.

When the crew confronted Brown about the money issues, he locked himself in his hotel room and refused to speak with the crew, Chelmo and associate producer Dan DeSantis said. Brown denied the claim and said he did not recall being confronted.

DeSantis and two other crew members confirmed that the production had money issues and salaries were not paid. Brown said he reached out to crew members this year “asking them what they were owed so I could make it right.”

The film’s director and screenwriter, Ramon Hamilton, said Brown told him at the time a casting director had been able to attach Wahlberg to the film. DeSantis confirmed that Brown repeatedly told them Wahlberg was connected. But when Hamilton called the casting director about it, she said it was not true, according to Hamilton.

“She said, ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about,’” Hamilton said.

Brown told The Times that Wahlberg was never connected, though they did send an offer.

“It was pie-in-the-sky dreams,” Brown said.

Brown declined to say whether he told the crew that Wahlberg had signed on to the movie.

Soon after, Brown was arrested by the Boston Police Department for allegedly skipping out on a $17,000 bill at the Liberty Hotel.

Brown claims that the hotel debt was discharged during his 2015 bankruptcy case and that the hotel never fought it. He spent two months in jail in Boston on charges he claims were bogus, according to his memoir, which he titled “And Still, I Persevered ...”

The criminal case remains open and a pretrial hearing has been set for May 30, the district attorney’s office said.

RJ Mitte was looking forward to acting alongside Kevin Spacey.

The two had signed on to star in 2015 in the low-budget indie film “Triumph,” about a high school student with cerebral palsy who joins his school’s wrestling team. For Mitte — who made his name playing Walter White Jr. on the iconic TV series “Breaking Bad” — the screenplay‘s focus on a disabled character was important because he has cerebral palsy in real life.

Mitte had met Brown on the set of his last film, “Who’s Driving Doug,” at which Brown was the unit production manager, said Mitte’s manager at the time, Melinda Esquibel.

Brown told potential investors that he had booked a screening for the film, which hadn’t been made yet, at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah, according to emails attached as exhibits in bankruptcy proceedings.

Spacey, who had not yet been accused of sexual misconduct and was at the height of his celebrity from “House of Cards,” had agreed to act as the wrestling coach for just $100,000, according to producers on the film. He had a niece with cerebral palsy, so he would do the small-budget film for less than he usually made, Brown told investors, their lawsuit said.

But Spacey never signed on and was unaware of the production, said Joanne Horowitz, Spacey’s former manager.

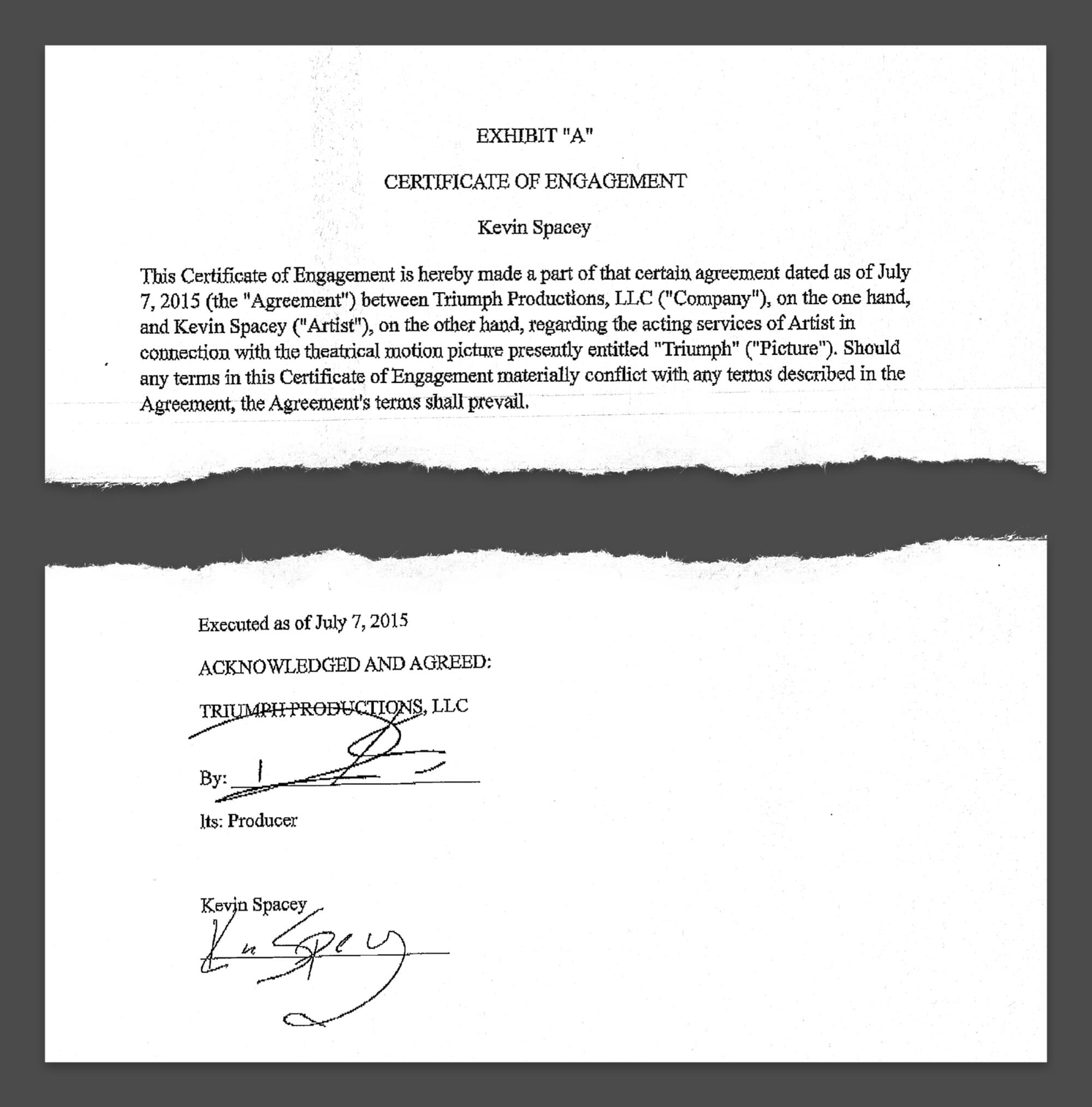

Brown had forged Spacey’s signature onto a fake contract to induce Mitte and investors to buy into the film, according to a civil lawsuit filed by investors against Brown, bankruptcy court rulings and a Tennessee judge’s ruling.

Brown denied forging Spacey’s signature on the contract. He said someone else did, without providing evidence, and blamed his ex for misleading him about Spacey’s interest in the project.

“We got [Spacey] through him,” Brown said.

But Horowitz said she was contacted solely by Brown and passed on the project. And the forged contract has Spacey’s and Brown’s names signed.

“The only guy that contacted me was a guy named David,” she said, adding that she was “100% certain” it was Brown who asked to connect Spacey to the project.

“You see paperwork, you see info and you’re told things and you believe them because you have no reason to doubt them,” Mitte said in an interview. “It was just one thing after another that continued to spiral out of control.”

On the day Spacey was supposed to show up on set in Tennessee, another man was used to block off Spacey’s scenes, Mitte said. Still, Mitte claimed that producers told him Spacey was coming.

After they were deep into filming, Esquibel said she learned that Spacey was not involved.

She called Horowitz, who informed her that Spacey had never taken the role, Esquibel said. Horowitz confirmed that Spacey’s signature was forged onto the “Triumph” contract. She had declined to attach Spacey when Brown initially reached out about the film, she said.

Horowitz said she and Spacey’s lawyer sent a cease-and-desist notice to the producers of “Triumph,” requiring them to stop saying that Spacey would be in the film.

“I had a heart attack,” Esquibel said. “I gagged. I didn’t know what to say.”

Brown finally did tell the crew that Spacey would not be involved.

“It was just one thing after another that continued to spiral out of control.”

— RJ Mitte

“Sometimes in this industry, talent availabilities change,” he wrote in an email reviewed by The Times. “I know we all took on this job in hopes of working with our ‘A list’ talent, but, now that his availability has changed and he can’t shoot till the first week of November, as a producer, I have a fiduciary responsibility to my investors to finish the movie.”

Brown added that he would increase the day rate of all crew by $25. But many did not see the increased pay — or what they were previously owed, several crew members said.

Dozens of people were never paid for some of their work, and production coordinator Ashley Amezcua calculated the missed pay exceeded $150,000, based on a spreadsheet she compiled that was reviewed by The Times.

Brown disputed the figure but didn’t elaborate.

Investors in the film sued Brown in 2015, saying that they were duped into giving their money and that they were told Spacey’s connection to the low-budget film would bring in big profits. Brown filed a Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

A Tennessee judge found in 2018 he committed fraud and ordered him to pay more than $1.7 million in damages.

“Defendant [Brown] engaged in actual fraud which has significantly damaged plaintiffs,” wrote Judge Ellen Hobbs Lyle in an April 2018 decision.

A bankruptcy judge also found that Brown had committed fraud, but later lowered the amount he owed to $384,000. Brown says he paid off the debt: “I have honored the terms of the settlement.”

Two years after “Triumph” was shot, Chad Darnell met Brown in Georgia on the set of “Killerman,” a movie starring Liam Hemsworth. Darnell was the location casting director and found Brown, the production supervisor, friendly and responsive.

Brown offered to finance Darnell’s debut, “The Undertaker’s Wife.”

Darnell shot the film in early 2020, but it was never sold or released because of disputes Brown had with investors, Darnell said. Brown has been sued by Todd Lundbohm, the investor behind “The Undertaker’s Wife” and another Brown film. Lundbohm claims Brown transferred more than $500,000 in film funds to personal, unrelated bank accounts. He alleged in the suit that Brown owes more than $1.2 million in damages.

Brown has denied the claims. “Every penny of the $1.1m he financed in Undertaker was accounted for,” Brown said in an email.

The case is pending.

Darnell had no idea that there had been any financial issues on “The Undertaker’s Wife” until he was informed by The Times.

In April 2020, Brown decided to shoot Darnell’s next film, “Intelligent.” Darnell, who lives in Atlanta, came to Los Angeles in July 2020 to begin preparations for the film.

But Darnell said Brown continually delayed the shooting for almost three years while stringing the director and cast members along.

Brown said a medical issue caused the delays and denied that he strung anyone along. “I’m disappointed to hear Chad slander and misrepresent facts,” he said.

In January, 10 days before the start of filming for “Intelligent,” agents and managers for lead actors Matthew Daddario and Katherine McNamara were asking for escrow, a common holding fee that actors receive before production. But Brown never sent it to the actors, Darnell said.

Because of this, the managers and agents pulled their talent from the film, Darnell said.

Brown claimed that it was a timing issue.

“We never escrowed talent because talent schedules never worked out,” he said.

Texts and emails from the agents show them asking for the escrow money repeatedly. A person close to both actors, who was not authorized to speak publicly, denied Brown’s claims and said the lack of escrow was the reason talent was pulled.

Meanwhile, Brown was struggling with other money issues. He was sued in November and then again in April over his role as production accountant on Duchovny’s “Bucky F*cking Dent,” with lawyers for the production accusing him of theft, wire fraud and more.

“You can tell he has experience,” said LeBarre. “The irony is I think he could be a damn good accountant if he wanted to be.”

But instead, the filmmakers allege in the suit that their production accountant had left them with massive money issues.

“Actors, contractors and crew have gone unpaid ... because of you,” wrote a lawyer for the film in a demand letter to Brown in November that was attached as an exhibit to his lawsuit.

The letter came weeks after LeBarre had been desperately texting Brown about payment problems.

“Not a single cast member has been paid, buddy,” LeBarre wrote Brown in an Oct. 27 message viewed by The Times.

Brown did not respond to a series of messages from LeBarre about payments, according to the messages. Brown told The Times he believed everyone got paid.

The filmmakers accused Brown in the lawsuit of skimming more than $710,000 in production funds for himself by transferring them into accounts that were unrelated to the film. Brown did eventually return more than $500,000, attorneys for the film said. Brown also “unilaterally” hired his husband and sister to serve as accountants on the film, paying them salaries without letting the filmmakers know, the lawsuit says. He also paid himself a salary of $3,700 per week, according to the suit.

“Without authorization, he made the hires and paid his household even more money than the production funds he was simultaneously stealing,” wrote Bucky Dent the Film LLC attorney Michael Mancini in the lawsuit filed in federal court in Los Angeles on April 3.

The case was initially filed in November, and in February, Brown agreed to return $197,500 he still owed. He sent a check to the filmmakers, which bounced because it was drawn against insufficient funds in Brown’s bank account, according to the refiled lawsuit, which is pending.

Brown said he did not steal money from the film, which he said was over budget.

He said the check he sent that bounced was meant to be held, though he did not offer any proof, and he cited emails showing he worked with a card processor to promptly approve payments when he became aware of the problem.

Around the time producers with “Bucky F*cking Dent” said they discovered hundreds of thousands of dollars missing, Darnell had just started as a producer and casting director on “Untitled SLA,” his third project with Brown.

The movie, about the abduction of Patricia Hearst, would be Brown’s directorial debut, with a $7-million plus budget, according to documents viewed by The Times.

Meredith Petran took a job as a production coordinator on “Untitled SLA” after working with Brown on “Bucky F*cking Dent.”

“He’s very nice, charming, can be funny. He’s definitely quick to respond to any slights. He gets really, really, really defensive and he has a volatile temper,” she recalled.

“I’ve never been accused of having a tempter or being volatile. I actually pride myself [on my] kindness,” Brown said in an email, misspelling “tempter.” “I’m actually a really sensitive guy.”

Petran was able to hire a crew for “Untitled SLA,” which was supposed to film in early November. Much of the cast was hired. Travel was arranged and some of the talent was put up at hotels in Los Angeles, Petran said. But the date for shooting kept getting pushed — and the crew stopped getting paid, according to seven crew members and emails from the time reviewed by The Times.

Brown admitted that crew members weren’t paid for the “last week or two weeks” on the project after financing fell through, but insists he paid out $160,000 of his own money to make crew members whole.

Corey Stram, a set decorator on the film, said he is still owed $8,500 for two weeks of work.

“He has delusions of grandeur,” Stram said.

In their lawsuit, producers of “Bucky F*cking Dent” also accused Brown of using money from that film to fund “Untitled SLA.”

A production services company also sued Brown in February in Georgia for fraud over “Untitled SLA,” alleging the crew was not paid and it was left on the hook for hundreds of thousands in wages it says Brown owed.

Still, Brown said he was trying to make the movie.

“The film is trying to come back in July. Financing is being worked out as we speak,” he said.

Darnell said that his experience on “Untitled SLA” was excruciating and that he also wasn’t paid what he was owed for casting and working as a producer before the project fell apart.

After “Untitled SLA” fell through, he said, he finally realized he couldn’t work with Brown.

He was broke and buried in credit card debt. He started driving for Uber and Lyft in Atlanta.

“I believed him,” Darnell said. “I absolutely believed him. And he betrayed that trust.”

Most who worked on the 2015 production “Triumph” and the brief 2010 “Dorchester Avenue” project with Brown had not heard from him for years, even more than a decade for some, and had long since given up on receiving the hundreds or thousands of dollars in compensation they say they were still owed.

But last month Brown sent messages to crew members on “Triumph” and “Dorchester Avenue” saying he could send them the money they were owed any way they like it — Venmo, Cash App, whatever — according to emails reviewed by The Times.

There was just one catch. They had to sign a non-disclosure, non-disparagement agreement.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.