Commercial shoots are driving Hollywood’s reopening, but crews worry over COVID-19

For Lindsey Clough, June 15 was a memorable date. The wardrobe stylist celebrated her 38th birthday on the same day filming finally resumed after the COVID-19 pandemic had shut down production.

The Eagle Rock mother of two had spent nearly 100 days at home with her family, without even a visit to a grocery store. Then she was back on a South L.A. set filming a commercial for a big brand.

She expected to see mask wearing, social distancing, widespread sanitizing and other safety protocols. But she was alarmed by what she saw.

“I started to notice that some things just weren’t happening,” said Clough, who has worked on commercials for McDonald’s, BMW and other big brands.

The van used to transport crew to and from set wasn’t sanitized between uses. Windows were sometimes closed and crew members occasionally took off their masks to eat in the van, she said, contrary to guidelines developed for commercials producers. She raised her worries with the person in charge of compliance with COVID-19 safety, but says her concerns were ignored. She decided to drive her own car on set.

“They might have thought I was overreacting, but I have the right to a safe workspace and to get the things that I was promised,” Clough said.

As Hollywood returns to production, crew members have voiced concerns that some commercial shoots are cutting corners on safety measures intended to protect workers from outbreaks of the virus.

Last month, Clough was among 700 crew members who signed a letter to the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), calling for more stringent COVID-19 safety protocols for those working on commercial sets. They argued that the existing guidelines are lax compared with the more rigorous measures that apply to film and TV productions, which require mandatory testing and COVID-compliance officers.

“We are each working under individual and variable levels of safety,” stated the petition, first reported on by Deadline.

Jonas Loeb, spokesman for IATSE, which represents 150,000 crew members working on productions in the U.S. and Canada, declined to comment.

Commercial productions are big employers in Southern California. Advertising-related shoots, including live-action commercials, have accounted for half of permits issued in the Los Angeles region since production resumed in June, compared with the typical level of 25% before the pandemic, according to FilmLA, which handles film permits for the city and county.

FilmLA President Paul Audley said he was not aware of any safety compliance problems on commercials permitted to film in the county.

After months without work, some crew worry about having to turn down jobs in order to keep their families safe from disease.

“Once you’re actually there and on set, you start to feel as people really fall back into their old way of working because we’re just so conditioned to please and to work very quickly and to say yes to everything,” Clough said. “You don’t know that in a crew of 60-plus people, that everybody takes this virus as seriously as you do.”

Hollywood unions are still hashing out the finer details around safety guidelines agreed to earlier this summer with major studios. The measures require employers to use effective testing methods and outline protocols around protective equipment, social distancing and sanitization of gear and equipment, including vans.

The unions released a more detailed paper in June called the Safe Way Forward, including steps such as how often different cast and crew should be tested given their exposure and requirements for compensation if a member gets sick. The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers has yet to agree to this.

The guidelines developed in June by the Assn. of Independent Commercial Producers, whose members are involved in making 85% of all commercials aired nationally, differ in many ways from either of those two.

For example, while the AMPTP and union-formed white paper suggests “one or more autonomous COVID-19 Compliance Officer(s) with specialized training, responsibility and authority,” the AICP guidelines recommend nominating a COVID-19 compliance assistant.

Evan Rohde, a Venice-based production designer who helped organize the petition to IATSE, wants the same level of safety across productions.

“When you look at all these stories put together, it’s not that one production screwed up or one production succeeded, but the inconsistency across the board is what’s so challenging,” Rohde said. He has relied on his savings and got a small loan to tide him over as he doesn’t believe it is safe to go back to work.

One other complicating factor is that crew can work both non-union and union productions. Non-union productions don’t have to comply with union guidelines.

AICP President Matt Miller said the letter to IATSE was the “opinion of a handful of [union] members not based on fact.”

He said it’s not practical for commercial producers to follow the same set of guidelines as film and TV crews, which have larger crews and shoot over longer periods.

Miller said the association’s guidelines have kept commercial sets safe from outbreaks of the virus.

“Certainly we’ve seen cases, but they haven’t led to outbreaks, which says that when you are doing all the things that need to be done,” he said.

Under the AICP guidelines, testing for fevers or for presence of the virus in a crew member is not mandatory. Instead, the guidelines require a questionnaire about symptoms that crew fill out themselves. L.A. County health officials have exempted short-running productions such as commercials from testing workers.

“The opt-out recognizes the unique nature of commercials and the size of the crew as well as the duration,” said Miller.

The fastest antigen tests are not as reliable as nasal swabs, and the more reliable ones are less available, Miller added.

Miller said his group has asked union representatives to flag any safety issues they witness.

“Anybody seen not complying with the protocols should be fired immediately and sent packing and not rehired,” he said.

SAG-AFTRA, which represents 160,000 actors and other performers, believes commercials should be testing like bigger shoots.

“We view the fundamental safety protocols as applicable across all types of work,” said Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, SAG-AFTRA’s chief operating officer and general counsel, who is leading the union’s safety and reopening initiative. “Testing should be in place unless an exception is warranted, such as when performers work entirely from home. How anyone can say there’s no value in getting tested because the production is of short duration, our scientists disagree completely with that, and logic disagrees with that.”

Moreover production assistants should not double up as COVID compliance supervisors, he said. “They have to have a level of authority that people will take them seriously,” he said.

L.A-based director Kim O. Nguyen, who has worked remotely on three commercials since the restart, said she told employers to plan for new working conditions. “It’s important for myself as a director that I have conversations with clients and agencies to discuss how important safety is, that things will take longer, that we need to be more patient,” she said.

Hollywood’s unions are gatekeepers to the entertainment industry, yet Black crew members say getting access for recognition for minority members is hard.

West Hollywood-based camera assistant Daisy Smith, who signed the petition, worries about the rush to return to production, noting that film sets are typically busy, crowded places with crews rushing around to meet tight deadlines.

On one job, a crew member had tested positive and production was suspended until all the crew could be tested, said Smith, a 30-year veteran of commercial shoots. On another job, a person in charge of compliance did not appear to enforce rules and there were no hand-washing stations.

“The hand sanitizer ran out and I came away from that just thinking nothing has changed at all about the way production is run, except now we wear masks,” Smith said.

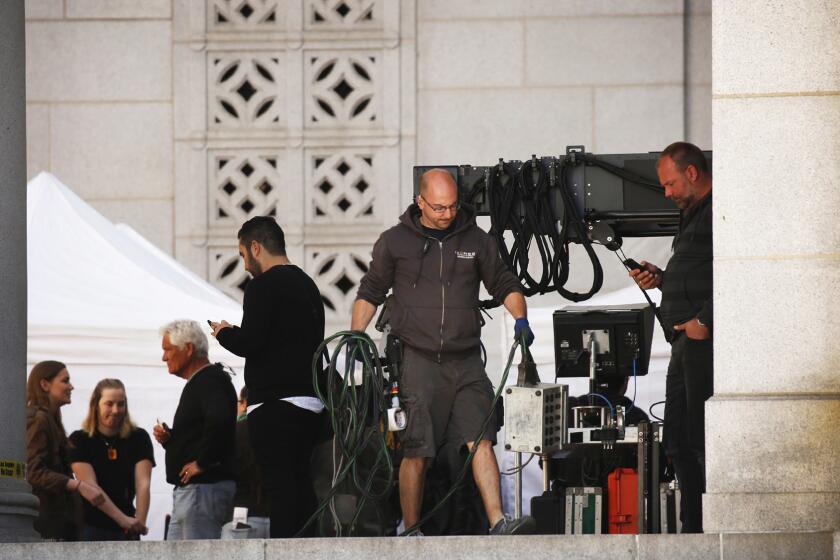

Location film shoots are gradually returning to the streets of Los Angeles even as the coronavirus health crisis renews.

Similarly, Clough witnessed others doing what she believed was unsafe, such as 15 people crowding into the bedroom of a house to film a scene. Part of the problem, she said, was often that the person charged with enforcing safety guidelines either wasn’t around or didn’t seem empowered.

“They are such well-meaning documents,” she said of the safety guidelines. “But when things start costing money and things start going very quickly, they will be thrown out the window.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.