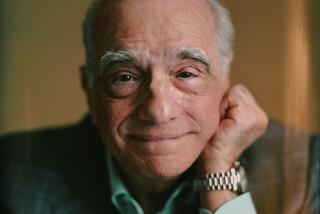

Why Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Irishman’ is so important to Netflix

Netflix has made expensive quasi-blockbusters like “Bright,” acclaimed Oscar fare such as “Roma” and a multitude of romantic comedies and Christmas movies. But the streaming giant has never released anything quite like “The Irishman,” a 3½-hour, $159-million crime epic from one of the lions of cinema, Martin Scorsese.

Opening in select theaters in Los Angeles and New York on Friday, the sprawling drama marks the highest profile film debut yet for the streaming giant, which has made movies a key part of its streaming business after years of disrupting the television industry.

For Netflix film chief Scott Stuber, who joined the firm more than two years ago, the Scorsese picture is part of a mission to prove that the streamer — widely seen as an outsider and, by some, an enemy of traditional Hollywood — can make movies that stand up among studio giants.

“The Irishman,” which tells the story of hit man Frank Sheeran, comes with serious gangster flick pedigree. Robert De Niro reunites with the “Taxi Driver” auteur to play Sheeran, while Al Pacino stars as notorious union boss Jimmy Hoffa and Joe Pesci plays Mafioso Russell Bufalino.

“For us the most satisfying thing is an artist like [Scorsese], and all these incredible actors, making this film that we’re all proud of, and will hopefully be a big event to audiences all over the world,” Stuber said in an interview this week.

From “Taxi Driver” to “The Irishman,” Martin Scorsese has created indelible films for the American imagination. He’s not done just yet.

Beyond the prestige factor, “The Irishman” is part of a larger push into quality filmmaking that Netflix hopes will draw subscribers to its service as it faces an onslaught of competition from studios that have been creating cinema since the early days of the art form.

Burbank-based Walt Disney Co. is poised to launch its Disney+ service Nov. 12 with a huge catalog of Marvel, Star Wars and Pixar movies, along with its vault of animated classics. AT&T Inc.’s WarnerMedia on Tuesday unveiled its ambitious plans for HBO Max, which will be the streaming home of DC superhero films, the Lord of the Rings franchise and classic movies from the Warner Bros. and MGM libraries.

As competitors encroach on its turf, Netflix is set to lose much of the older film and TV content studios supplied to the service. As popular licensed material like “Friends” and “The Office” leaves Netflix, the company will have to rely more on its in-house content, including film. To that end, the company is releasing 18 movies this quarter — a company record in terms of size and scope for its film releases — including the Eddie Murphy vehicle “Dolemite Is My Name” and the upcoming Michael Bay action movie “6 Underground.”

“At the end of the day filmmakers want their films to be seen, their work to be out there in the culture, and that happens on Netflix better than anywhere in the world,” Netflix Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos said in an recent interview with The Times.

Some analysts worry that Netflix’s spending levels are unsustainable. The company is expected to spend $15 billion on content this year, fueled by growing long-term debt. But longtime Netflix bull Rich Greenfield, a partner at New York-based research firm LightShed Partners, said the company’s movie strategy adds more value to the platform and should help Netflix retain customers, even as the market gets more crowded with lower-priced services.

“It’s going to allow Netflix to not only increase engagement with the Netflix service, but it’s also going to allow them a lot of pricing power over the long term,” Greenfield said of Netflix’s movie slate.

And despite the influx of competitors, the company remains confident in its strategy of attracting top-tier filmmakers by promising high levels of creative freedom and by being willing to take risks. Netflix recently cited three films as “early Oscar front-runners”: Noah Baumbach’s “Marriage Story,” featuring Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver; “The Two Popes,” starring Anthony Hopkins and Jonathan Pryce; and “The Irishman.”

A bold claim, to be sure, but one that serves Netflix’s aim to prove itself as a bona fide studio.

“When I got here two years ago, it was a place that wasn’t perceived in that manner,” Stuber said. “It was a lot of, ‘Oh, you guys don’t make good movies.’ And, truthfully, the athlete in me got mad about that and got competitive. So I’m glad we’ve hit some balls pretty far this fall.”

“The Irishman” will be a major test of Netflix’s evolving movie strategy, which has faced resistance from theater chains that are accustomed to long, exclusive windows for Hollywood movies before they’re available for home viewing. “The Irishman” will be available for streaming Nov. 27, four weeks after it debuts in limited theatrical release. The average big studio movie gets a nearly three-month theatrical window. Netflix has also ruffled feathers by not releasing box office figures for its movies, bucking a standard practice among the studios. After Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma” won four Oscars this year, the film academy faced calls to restrict awards consideration for streaming movies. Amazon Studios, in contrast, has largely conformed to standard theatrical practices, though its movies have struggled.

Many observers expected Netflix to secure a longer window for “The Irishman,” given Scorsese’s stature as a cinema giant accustomed to getting the big-screen treatment. But Netflix was unable to reach a compromise and major chains including AMC Theatres rejected the film.

Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman” — a much-hyped, three-and-a-half-hour Mafia world epic for Netflix — is a complete triumph.

Still, Netflix is waging a splashy theatrical rollout, starting this weekend in movie houses such as Los Angeles’ classic Regency Village Theatre, the Landmark, the new Alamo Drafthouse downtown and the Laemmle Monica Film Center. The storied Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, which Netflix is in the process of acquiring from American Cinematheque, is playing the film for two weeks. The movie is also being shown at the Belasco Theatre in New York, a Broadway institution.

Scorsese, asked by a Times reporter whether he felt caught between the worlds of streaming and old-school cinema, said the key point is that Netflix enabled him to make the film in the first place.

“In order to show a film, you have to have a film,” he said. “So let’s make it. This was a real offer and it made sense. The trade-off is this: an exhibition. But it’s still in theaters. While it’s being streamed it’s still in theaters.”

Stuber declined to comment directly on theater negotiations. However, he noted that Netflix has begun granting theatrical windows to more of its films, not just Oscar contenders like “Roma.”

“Last year, we moved into theatrical to show we understand that the audience wants that choice, and this year we’ve moved even further,” Stuber said. “We’re trying to find the right cadence to give the filmmakers what they want and give the consumers what they want.”

By any measure, “The Irishman” was a major risk. The movie, based on the 2004 nonfiction book, “I Heard You Paint Houses,” was previously in development for years at Viacom Inc.’s Paramount Pictures, but the studio grew worried about the ballooning costs and allowed Scorsese to shop it elsewhere, according to a person familiar with the matter who was not authorized to comment. The film required new technology, developed by Industrial Light & Magic, to dramatically de-age De Niro and the other actors without intrusive motion-capture techniques.

Netflix was willing to foot the bill. Stuber and Sarandos were wowed by ILM test footage in which De Niro, 76, re-created a scene from “Goodfellas,” portraying his much younger self with the age-defying tech. This past spring, Stuber and Sarandos trekked to ILM’s Northern California offices to view the effects and were similarly awestruck. “It was one of those great moments when you get that giddiness of seeing something remarkable that’s going to help evolve the business,” Stuber said.

Netflix betting on “The Irishman” should help curry favor with filmmakers, said Jason Helfstein, a managing director at Oppenheimer & Co. “It’s a way to attract talent who may not have worked with Netflix before to see that they are a good partner,” Helfstein said.

The company that defined the concept of binge watching has continued to reinvent itself. But as Disney, Apple and others enter the streaming business, Netflix faces the biggest challenge in its history.

Stuber, a former Universal Pictures executive, stressed that Netflix must continue to attract quality directors and producers in order to build its film library from the ground up. For example, Netflix in August secured a film and TV deal with “Game of Thrones” producers David Benioff and D.B. Weiss.

“When you’re starting from scratch, and you don’t have a library where you can remake ‘Charlie’s Angels,’ and you don’t have things like Marvel or DC, you have to build off great filmmakers, unique stories and movie stars,” he said. “And we’ve been building that pace.”

Times staff writer Jeffrey Fleishman contributed to this article.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.