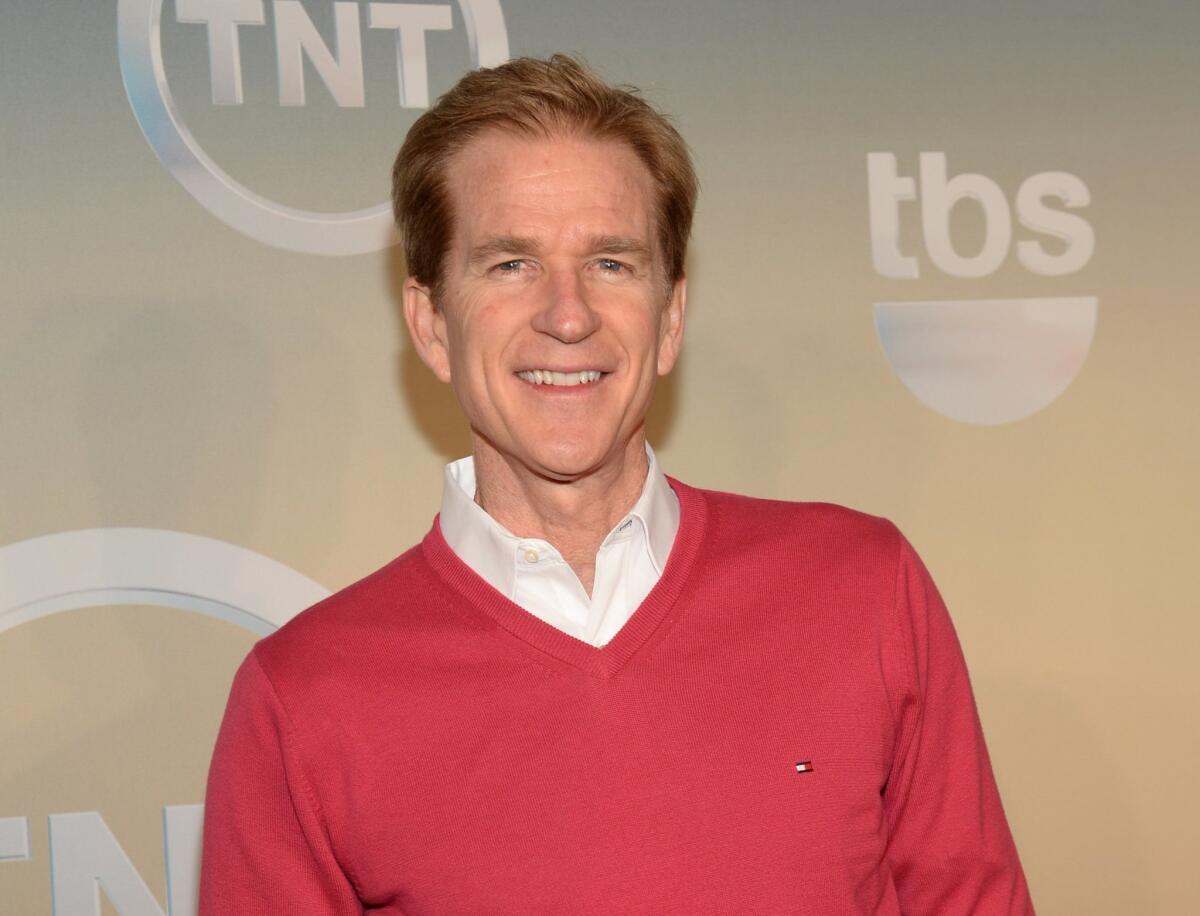

Film school’s ties with Matthew Modine face scrutiny in heated SAG-AFTRA election

The videos are short and breezy: “Actors don’t act alone,” intones Matthew Modine (“Stranger Things”) in a voice-over, as quick clips fly by from favorite movies and television shows.

His message: Don’t ignore the important contributions of the nameless stunt performers who make popular media exciting. Or the work of background performers or singers and dancers.

But the three videos, deployed on Modine’s campaign website as he runs for SAG-AFTRA president, have become the focus of controversy as the veteran actor seeks to oust incumbent union president Gabrielle Carteris (“BH90210”) in a heated election battle.

They highlight the entanglement between Modine and the for-profit school, New York Film Academy, which produced the videos at no cost to Modine.

Modine sits on the film academy’s board of directors and donates money to support scholarships in his name, amounting to $25,000 to $100,000 annually, according to the school’s website.

NYFA promoted Modine and his slate’s candidacy via Twitter and in an April 29 post on the school’s website that linked to his GoFundMe page, then produced and rolled out the three videos on July 3 as the election heated up.

Stunt and background performers, whom Modine praises in two of the videos, are key electoral constituencies for MembershipFirst, a faction in the union that is running dozens of candidates for officer, board and delegate slots in an election that will conclude Aug. 28.

Optics aside, at least one legal expert and Modine’s chief opponent are asserting that the use of the videos runs afoul of a federal labor law that prohibits union candidates from receiving and using cash or in-kind contributions from any employer.

According to a U.S. Department of Labor manual, “no employer may contribute cash or anything of value to the campaign of any candidate.” SAG-AFTRA’s rules for candidates echo the federal law.

Veteran labor lawyer Michael Wolly said the use of the NYFA videos on MembershipFirst’s campaign website and YouTube pages — where the videos were co-branded for the slate and the school — is a “per se violation” of federal law, using a legal term that means “inherent” or “automatic.” Wolly, a union-side attorney at Zwerdling, Paul, Kahn & Wolly in Washington, D.C., added that “the law does not allow employer funds or support to be used in a union election.”

If Carteris or her slate lose, labor department officials could void the election and force a redo under federal supervision, he said. Under the statute, that process could be triggered by any member of the union filing a protest based on the videos.

The school and Modine’s campaign acknowledge that NYFA provided the videos to him for free but deny they did anything wrong.

Modine was not available for an interview. His publicist Adam Nelson said the actor “asked for and received permission from NYFA to post the PSAs on the MembershipFirst website.”

Nelson confirmed that the actor did not pay NYFA for the videos, but contended there was no legal violation because the videos were intended as public service announcements and were educational, not political.

“NYFA created these PSAs for the purpose of educating the public on the importance of contributions made by stunt performers, singers and dancers and background actors in modern film and television,” Nelson said. “Modine donated his services as a voice-over actor for the PSAs because he strongly believes that stunt performers, singers and dancers and background actors’ contributions are important.”

How did a film school that regularly appears on Hollywood Reporter and Variety recommendation lists and boasts nearly a dozen locations around the world find itself caught up in the arcane and bare-knuckle world of union election politics?

Dan Mackler, dean of the school’s Los Angeles campus, said the videos “were done for educational purposes” and that no students were involved. The language of the federal statute contains no exemption for educational materials.

These are “areas of the law which we have had no prior dealings,” said Mackler, who also serves as the film school’s chief strategy officer and senior vice president.

The school’s involvement has incensed Carteris and her Unite for Strength / USAN slate, which has battled MembershipFirst for more than a decade.

“These aren’t just flagrant violations of our union election rules, but of federal labor law as well,” Carteris said. “It says a lot about Mr. Modine and MembershipFirst’s poor decision-making, something we clearly can’t afford in our upcoming contract negotiations,” she added, referencing the union’s upcoming TV and theatrical talks with the major studios ahead of a mid-2020 contract expiration.

The videos on NYFA’s website and YouTube pages received about 15,000 total views before the school had them taken down after a reporter’s inquiries.

“This is very unusual and untoward for an employer to contribute,” said Thomas Lenz, a management-side labor lawyer at Atkinson, Andelson, Loya, Ruud & Romo and a USC law school lecturer. “It sounds really entwined.”

The law at issue, known as Section 401(g) of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA), provides that “no moneys of an employer shall be contributed or applied to promote the candidacy of any person” in a union election. Corresponding regulations specify that money includes “anything of value” and “employer … is not restricted to employers who employ members of the labor organization in which the election is being conducted.”

Similarly, SAG-AFTRA’s election rules warn that “The prohibition on employer contributions extends to every employer, regardless of the nature of the business or whether any union represents its employees.” The union sends out a detailed warning to studios, production companies and talent agencies during elections.

Labor-side lawyer Bob Giolito, who represented SAG during its 2012 merger with AFTRA, declined to address the Modine situation specifically. But he said employer contributions are “verboten” and that “The Department of Labor takes a very hard line on this stuff.”

SAG-AFTRA and the Department of Labor declined to comment.

Court decisions and settlements under the law seem unambiguous.

In one case, a union election was undone because a candidate made $6.40 worth of copies on an employer’s copier. Another was voided when a zealous supporter, acting without the candidate’s or employer’s knowledge, parked two employer trailers at a polling site, then plastered them with campaign signage.

Other cases that required new elections involved free use of employer computers, email accounts, fax machines, bulletin boards, or advertising and design services. Use of a church photocopier passed muster, but only because the candidates had prepaid for copies by contributing to a church fund. As a 2011 decision reiterates, “No minimum amount is required before [the employer contribution] prohibition is applied.”

An Atlanta slate that supports Carteris but is not part of her ticket also faced criticism for possible violation of the federal law after it received promotion on two employers’ Facebook pages earlier this month. SAG-AFTRA had those posts taken down and offered equal time to the opposing candidates, who refused the offer. The union then notified Atlanta members that they could request a replacement ballot and re-vote if they wished. “The Election Committee decided to take immediate action to ensure a fair election,” said an email from the union.

For their part, Carteris supporters have also raised questions about a June 29 New Orleans fundraiser for Modine that raised $7,243 for his campaign and featured food “generously donated” by six different restaurants.

Modine’s publicist Nelson said that the event was sponsored by a local committee. However, the invitation urged attendees to “join Matthew Modine … for an evening of … fundraising for his SAG-AFTRA presidential campaign,” and the payment link led to a GoFundMe page named after Modine and based in North Hollywood, not New Orleans.

In order to force a new election, the law does require that a violation “may have affected the outcome” of the election. But Wolly said that such an effect is all but presumed in cases of employer contributions. The 15,000 views garnered by the now-removed videos, plus the tweets and blog pages far exceed the likely margin of the five-way SAG-AFTRA presidential election — only about 29,000 members voted in the union’s 2017 presidential contest — and the margins in the board of directors race, where seats last time were decided by as few as seven votes.

The balloting concludes Aug. 28, but a successful challenge might require rerunning the national election and postponing the union’s October convention until officers, board members and delegates are elected under federal supervision.

The last time SAG had to redo a national election, in 2001, the process lasted four months.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.