How Jeremy Saulnier’s ‘Rebel Ridge’ took on police abuse and became a Netflix hit

On its face, the film “Rebel Ridge,” fronted by a largely unknown cast with a plot centered on civil asset forfeiture, doesn’t scream “global Netflix hit.”

But writer-director Jeremy Saulnier’s latest thriller has resonated impressively with streaming audiences, ranking as the No. 1 movie on the platform during its first two weeks in release and amassing nearly 70 million views as of Sept. 15, according to the Los Gatos, Calif., company.

The picture follows a former Marine (Aaron Pierre) who must confront a group of cops led by a corrupt chief (Don Johnson) after they confiscate more than $30,000 in cash that he intends to use as bail money for his cousin.

Taking inspiration from classic man-against-the-system revenge tales such as “First Blood,” the film activates the viewer’s inner civil libertarian with its portrayal of police abuse and government overreach.

Alexandria, Va.-born Saulnier, 48, has a knack for muscular, intense dramas that push his protagonists to their limits, achieving festival darling status with 2013’s “Blue Ruin” and 2015’s “Green Room,” about a touring punk rock band under assault from neo-Nazi skinheads.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

What do you think is making this film resonate with audiences?

I’m just so excited to see it explode. I definitely can never really put a finger on when things hit the zeitgeist like this, and I’ve never had a film that did it in this way. So I’m just kind of stepping back and enjoying the ride.

I mean, it is, in its own way, a political film in an election year. It activates people’s fundamental sense of unfairness at what’s happening on the screen. Do you get that reaction from people who’ve seen it?

Oh, yeah. You can certainly tell that many reactions are quite charged, mostly in a really good way. I actually wrote the film in 2018, so it took a while to get it off the ground, but it oddly seems perfectly timed. I personally have always been obsessed with justice, so I wanted to explore that. I’ve always gravitated toward films that get your involuntary reactions stimulated. I like grounded films. I want to be transported. I like a little fire in the belly. This film certainly, I think, ignites that in people.

I specialize in tension and creating these sort of slow-boiling movies. And unlike any other, I think this [movie] has more of an uplift to it. Certainly, it’s harrowing, and there’s some tragic turns, but I’ve never felt such a lift from an audience. Literally, I’ve seen people get out of their seats. I’ve seen people high-five. Whereas a lot of my films are infused with a little more dread.

There’s a lot of “First Blood” DNA in the movie, but it’s not Rambo. He’s not just spraying bullets and laying waste to his enemies. How did you figure out what Terry Richmond’s fighting style and ethical framework was going to be?

You know, it wasn’t so much his ethics as it was pragmatism on his part. He’s a movie hero. He’s highly competent. He has a high bar for integrity. But he even says it out loud in the movie, he didn’t come here to make things right. He’s not on that kind of mission. He’s just trying to survive.

I was trying to figure out a way to thread that needle where we could still have our protagonist carve through an army of antagonists but not increase the likelihood that he wouldn’t survive the journey.

Terry, throughout the whole movie, is actually using minimum force, even when he’s cracking elbows and knocking people out and brutally elbowing them. He needs to take them down and have them stay down. But they can’t be 6 feet under, if you know what I mean. I wanted this to be grounded and plausible in how he gets across the finish line.

This is your second Netflix movie after “Hold the Dark” (2018), which you collaborated on with your longtime friend Macon Blair. How does the Netflix experience differ from the typical process of getting an independent movie launched?

I always start my process very independently, in that I’ve never taken $1 to write anything. I spec out my scripts. I write them on my own, and I put myself at financial risk to maintain that control. I don’t fully know what the final film is going to be until I get through the second or third draft. And if you’re with the wrong partner at that point, that’s how films die.

Initially, for “Hold the Dark” [starring Jeffrey Wright], when we were out there in the independent space [talking to] typical studios and financiers, we hit a wall with foreign sales. That’s the model of casting movies to satisfy pre-sales, where they assign a dollar amount to people’s faces, and they can pre-sell territories and justify funding the film…. What I found with Netflix was, they embraced my vision of the film and they allowed for far more interesting casting.

[For “Rebel Ridge,”] I went back to Netflix for the same reason. I could cast who I wanted. I wanted to kind of flex some new muscles and find some new viewership out there. I didn’t just go to them. I took it out to market and immediately saw the options, which were very limited. There was some big studio interest, which I was very excited to have. But as my agent would say, the path to production at Netflix was much more assured. It wasn’t going to get overdeveloped and put on a shelf.

A big part of how indie films get financed is by pre-selling the international distribution rights. A lot of the time, your ability to do that depends on casting a recognizable face who can sell the movie on the poster in Italy. But Netflix buys all global rights, so you don’t really have to worry about that part of it.

Yeah, you get to bypass that part of the gatekeeping process. With foreign sales, this is based on existing data. It’s not just this horrible system. But it is backward-looking, and that’s why you get a lot of films funded in that model with actors who are amazing and have these long legacies. But there’s a very short list…. And for a filmmaker who’s looking to blaze new trails, it’s not always very exciting. And sometimes films don’t happen because the first six people on the list don’t engage.

It’s super interesting to think about all those trade-offs. With Netflix, you don’t get the big theatrical window, but it does have this global reach. And I think a lot of filmmakers are probably grappling with how to make sense of all that.

The thing you can’t control, of course, is word of mouth. And I think that’s where we were just really excited to have that work to our benefit.

You’re showing parts of the country that many people in L.A. and New York are probably only really familiar with from watching the news. What draws you to these kinds of settings? [“Rebel Ridge” was filmed in Louisiana.]

I was born and raised in a suburb of Washington, D.C., in Virginia, so you drive an hour outside the city and you’re in it. There are so many different reasons. I do gravitate toward more rural environments, and maybe it’s more of an aesthetic thing. I just love to be out there. It could be because I became a city dweller and I just need to clear my head and go tell stories where you can hear the stillness….

In my research [for “Rebel Ridge”], I was focusing on the practicality of these very corrupt systems and how they’re built. In some cases, it’s often just a complete lack of infrastructure or funding. They are sitting there on their own, and where the human connection comes in is the indifference that lets these systems continue.

As I noted in a previous newsletter, the film starts with Iron Maiden’s “Number of the Beast” and has some other great songs, like Bad Brains’ ”Right Brigade.” What role does music play in your filmmaking?

It’s vital. I’m a punk rock kid. When I’m writing a movie, I will start first with a big compilation of music that will inspire me. And I even do it in chronological order of what I think the arc of the film should be. “Green Room” was certainly wall to wall music. “Blue Ruin” was very score heavy, and it was really fun working with the Blair brothers [film composers Brooke and Will Blair] on that. I think we had a breakthrough. I was like, “The sound should be ‘liquid noir’” [laughs]. And that was done in four days under duress to make a festival deadline.

Also, you know, I was in a band; I was among really cool composers and musicians, and I’m always trying to get bands into movies. Like with “Green Room,” a lot of the songs were written by my high school friends back in 1993. Even in “Rebel Ridge,” there’s a Gut Instinct song I snuck in at the end for the credit crawl. The music scene kind of defined me, not just because of the music itself — the hardcore or hip-hop, or whatever. When I tap into that youthful energy, it’s always through music.

I’m sure people have told you this 1,000 times, but the Dead Kennedys cover in “Green Room” (“Nazi Punks F— Off”) is just off the charts.

When they gave us the rights to create our own performance, I was over the moon. That’s a big ask.

Even for “Rebel Ridge,” I’ve been asked, “What was the origin of the script?” It’s always hard to trace it, but I do remember Iron Maiden was part of the original spark. I wanted to start with some majestic metal and engineer a rug-pull. That very first image was accompanied by “The Number of the Beast.” I was privileged enough to be able to license that song. A few films ago, we just couldn’t afford that sort of thing.

With “Green Room,” we have so many musician friends and consultants. It was, “We can’t afford Motörhead. Just call up Midnight.” And they’re a friend of a friend. You find a similar song, and that becomes your first pick because it’s so awesome.

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

California’s film industry is in crisis. Can it be saved? The Golden State has a film and TV production problem. Industry professionals and experts are trying to determine what can be done to fix it.

How ESPN’s Scott Van Pelt and ‘Bad Beats’ keep ‘SportsCenter’ fresh in a YouTube world. Van Pelt’s late-night show has become the post-game show for ESPN’s big live events, where viewers come for the interviews and stay for bets gone awry. He’s starting his 10th season.

Smartmatic’s defamation lawsuit against Newsmax is headed to trial. What’s at stake? A defamation suit over Newsmax’s coverage of former President Trump’s lies about election fraud could be a major blow to the right-wing network.

As Hollywood and streaming go global, U.S. State Department leans on power of film. USC’s School of Cinematic Arts hosted a cohort of African filmmakers this summer as part of a State Department program for film diplomacy.

‘Hunger Games’ studio Lionsgate to partner with AI company. The Santa Monica-based “John Wick” company will partner with AI research company Runway to create and train an artificial intelligence model that can be used to help augment its work. The move is controversial, to put it mildly.

ICYMI:

Amazon MGM Studios is joining the studio’s lobbying group

Jennifer Lee steps down as Disney Animation chief

Lawsuit against James Dolan, Harvey Weinstein tossed

MrBeast, Amazon sued over ‘hostile work environment’

Film shoots

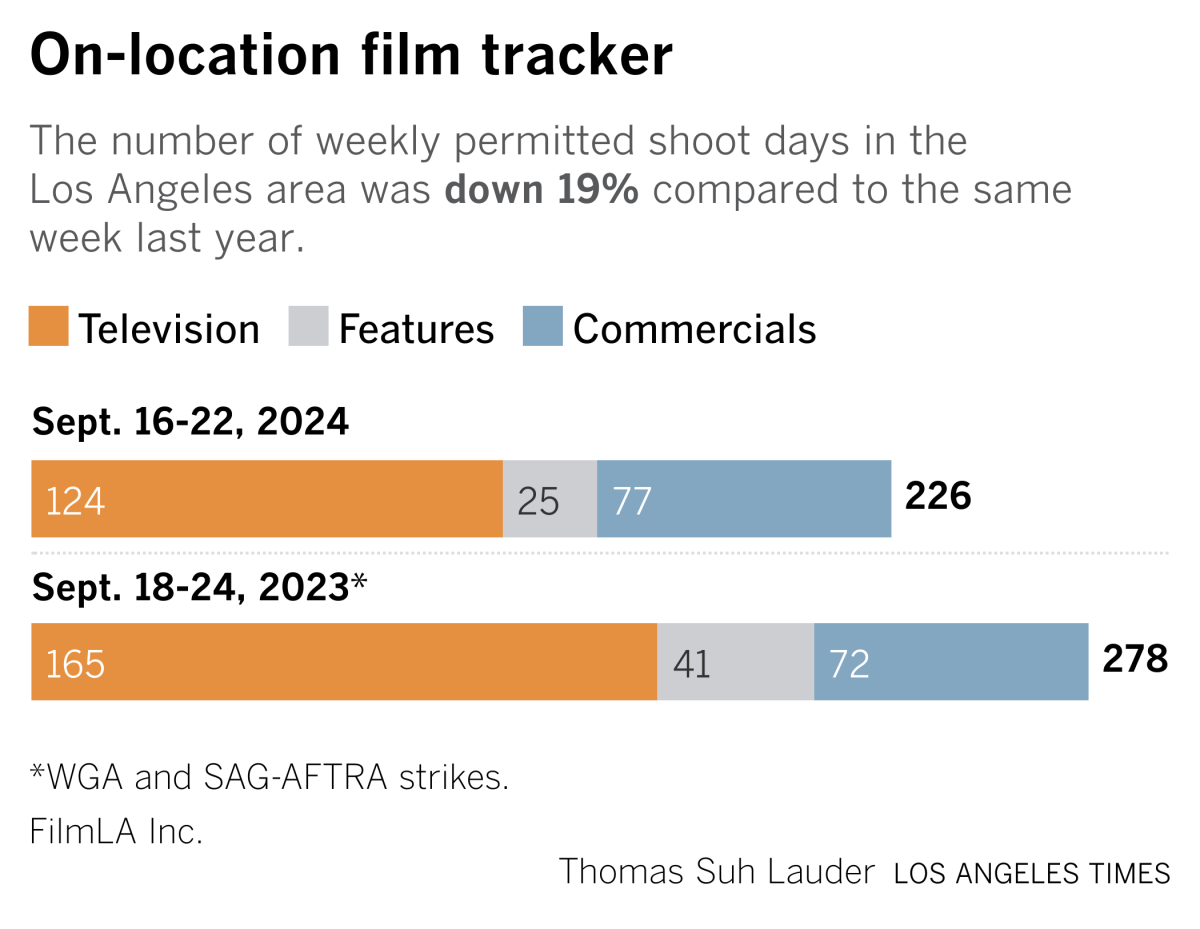

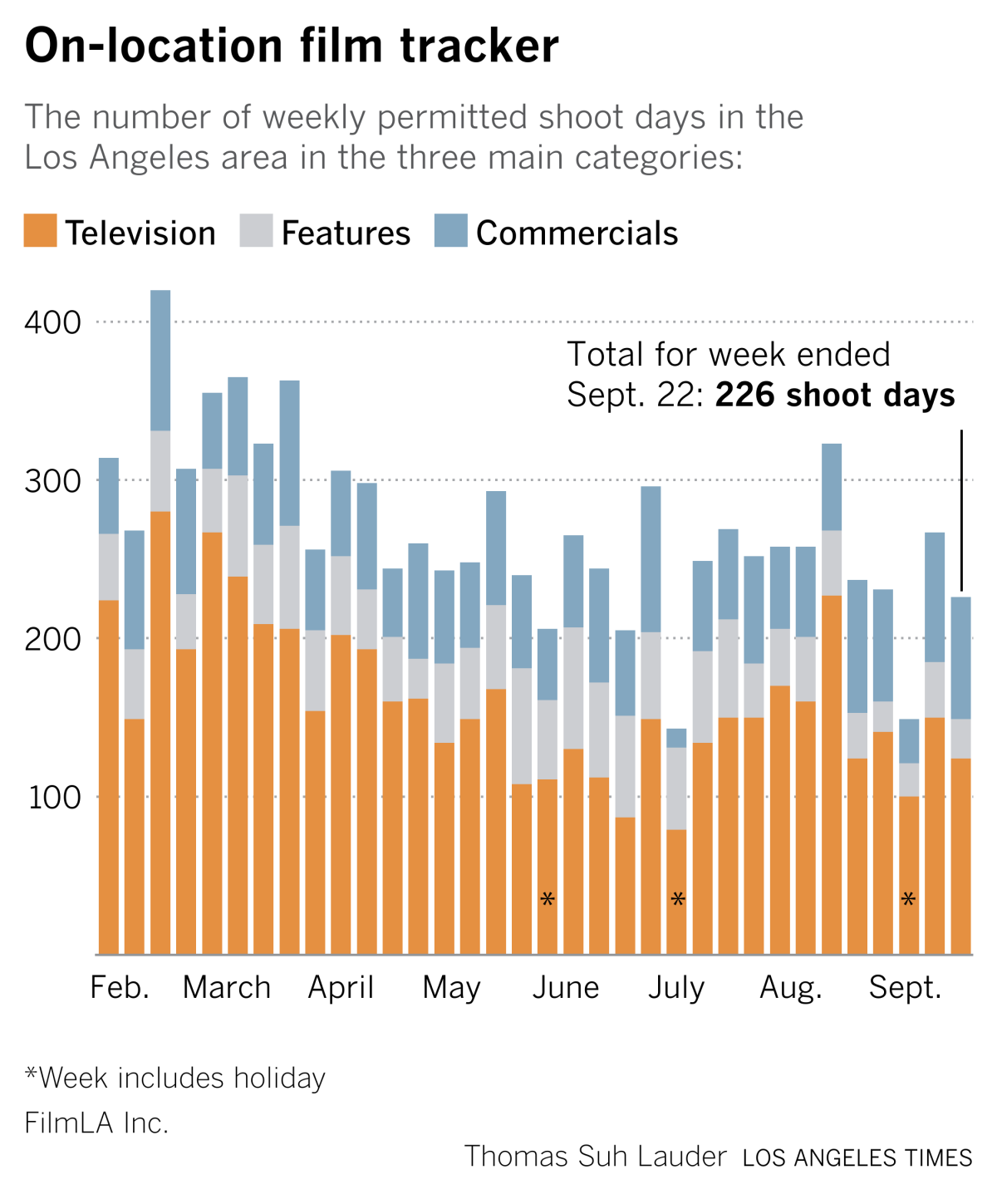

L.A. entertainment production: still weak. By the way, this week marks one year since the end of the WGA strike. The SAG-AFTRA work stoppage didn’t end until November.

Finally ...

This “Daily Show” sketch from a couple weeks ago, in which we meet the writer of all those horrible 2024 political campaign fundraising emails, will go down as one of the best of this election cycle.

Also, for no particular reason, I can’t stop listening to the Cure’s “Disintegration” (1989). This week’s walk-off song: “Pictures of You.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.