Sheila Heti recounts the ABCs of her evolution in new book of diary entries

On the Shelf

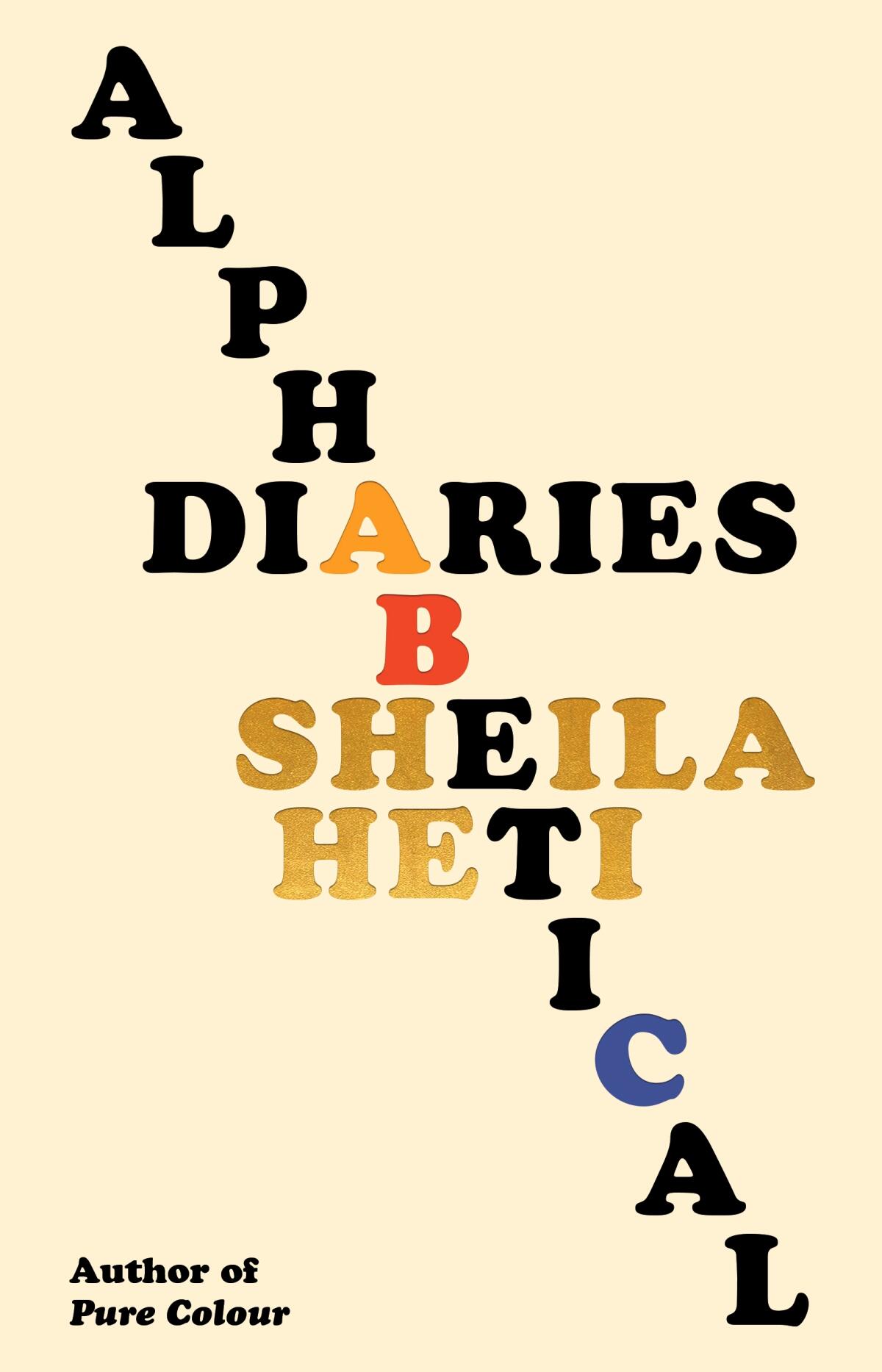

Alphabetical Diaries

By Sheila Heti

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 224 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores

Talking to Sheila Heti is disarming. Like her work, she is unself-conscious and brilliant, but in a way that you don’t always recognize as brilliant because of how open and accessible she is. Heti has made a career of doing what feels somehow both too obvious and impossible, writing a novel called “How Should a Person Be?” when, really, most novels circle that question. But in her hands, the question feels fresh and alive. Each book that Heti has written has pressed further into the possibilities of what fiction can be while staying grounded in the mining of the self.

In “Alphabetical Diaries,” Heti has once again tried something that feels impossible: collecting her personal diary entries for more than 10 years, reordering the sentences in alphabetical order, shaping, cutting, colliding, to build a different form of narrative. While the concept of “diary” feels illicit and unfiltered — and the pleasure of the ways you are peeking into something true and intimate is alive here — the genius of the book is in how broadly human and carefully constructed it also feels.

In ‘Come and Get It,’ author Kiley Reid unpacks the unsettling dynamics of college campus capitalism.

Heti started to collect the diaries in 2010. “How Should a Person Be?” had just been published in Canada (it would come out in the U.S. two years later) and borrowed heavily from her own experience — large sections of the book are recorded conversations Heti had with her friends. The book’s events track closely with those of Heti’s life, but it also contains fictionalized experiences. “I wanted to look back on the years that I had been writing that book and remember what was true.... I wanted to do something so I wouldn’t forget what my real life had been.”

For years, Heti had no intention to publish the diaries, “and then slowly, I started to think, this is actually interesting to read.” She broke them into individual sentences, then alphabetized them in a spreadsheet, “I think I thought that if I alphabetized them, I would be able to look at who I had been in a sort of systematic, removed, more scientific or analytical way, not getting lost in the various narratives or stories,” but for a long time she struggled with what to do with them.

At one point, Heti thought she’d publish the diaries online, as one 500,000-word document: “I was like, maybe it should be unreadably long but amazing for what it contains.” This is an impulse that comes up again and again in talking to Heti. She is always willing to try things; risk and failure are inherent in her project. She’s most interested in discovery and play.

As with every project, as she considered this catalog of sentences, Heti was in constant conversation with her friends. “I think my work would die of suffocation if it didn’t have my conversations with my friends as part of it, ” she says. In this case, two of her friends, an artist and a designer, “put all the sentences for each letter in a paragraph [as they are in the book] … and that kind of completely changed the book for me.” The paragraphs let her see the project more clearly as a novel, and she felt freer to cut and shape with a reader in mind.

Each of Heti’s projects has had a version of these steps. “I always start by gathering a lot of writing together. I try to make as huge a pot as possible … not making any discrimination at first … and those are the ingredients. … And then I go through asking, what energies can be found in putting this paragraph with this one. … They all could belong anywhere or be cut. … I like to think of myself, once I start editing, no longer as the writer but as maybe a chemist. What happens if these things are put together? Is there energy between them? Is there some kind of reaction or explosion?”

Much of the material of the previous projects came in the process of their creation, but with “Diaries,” it was only after the sentences had been accumulated that she began to mine it for a book. This was a useful access point to a clarity and candor that Heti’s always reaching for. “I’m always trying to get away from writing that is performance,” she said. “I wasn’t performing when I was writing because I wasn’t writing for anybody else. I was just trying to work something through. So it’s more like being a documentary filmmaker, to try to find documents that then can be formed.”

The writing had been individual attempts to capture moments, feelings, impulses; the reshaping was to shift those evanescent feelings into a coherent form. “I think the main thing about storytelling is the fact that you are putting life into a sequence. … I think we like it because it’s so different from what it feels like to experience life,” she said. The trick with “Diaries” was that the most traditional form of sequencing, linearity, was already taken off the table; the sentences had been re-systematized as alphabetical so Heti had to find her way to a different type of narrative.

But then this already showed itself to hold a sort of truth inside of it. “I think the way we perceive time as humans is really not what time is,” Heti said. “There’s so much more actual jumping around in time in life than a traditional kind of narrative can capture.” In real life, and in “Diaries,” we move to memories, yearnings, cast about into the future. In the cutting and reshaping — Heti chopped those initial 500,000 words down to 55,000 — she wanted to offer a sequence that felt pleasing and comprehensive, but also closer somehow to this experience of moving in and out of time.

By abandoning the constraint of time, new discoveries felt possible. One of them, she says, is how much more fixed and immutable most humans are. “One sentence from seven years later and the two go side by side. And it seems like a narrative. What is that? That’s not just editing. There’s also something true about life. There is this penetration of time within time and incidents that we live within other incidents.”

Also, she says, the format of the book highlights how mostly similar we are. “The self feels less personal to me now.… I think getting older you become less interested in your own self-image, your own reflection, and more curious about what do we all have in common.” One of the reasons, she says, that she felt no shame about the bits of herself we see in the diaries was because “I don’t imagine I’ve ever thought or felt a thing that other people haven’t also felt.”

Like life, “Alphabetical Diaries” is destabilizing at first. The brain casts about for sense or sequence to tether itself to. You track proper names, repeating ideas, sentiments. Gradually, something elemental, true and human, begins to form. There’s a particular thrill in feeling like a new sense of narrative is accruing inside of you as well. “I think the feeling I would hope of reading this book is that there’s some simultaneity of the living of the writer and the reading of the reader. The readers, I hope, feel like they’re being given something that is alive or that’s still being lived.”

Strong is a critic and the author, most recently, of the novel “Flight.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.