Rising-star author Anthony Veasna So died at 28. Now you can read his unfinished novel

Review

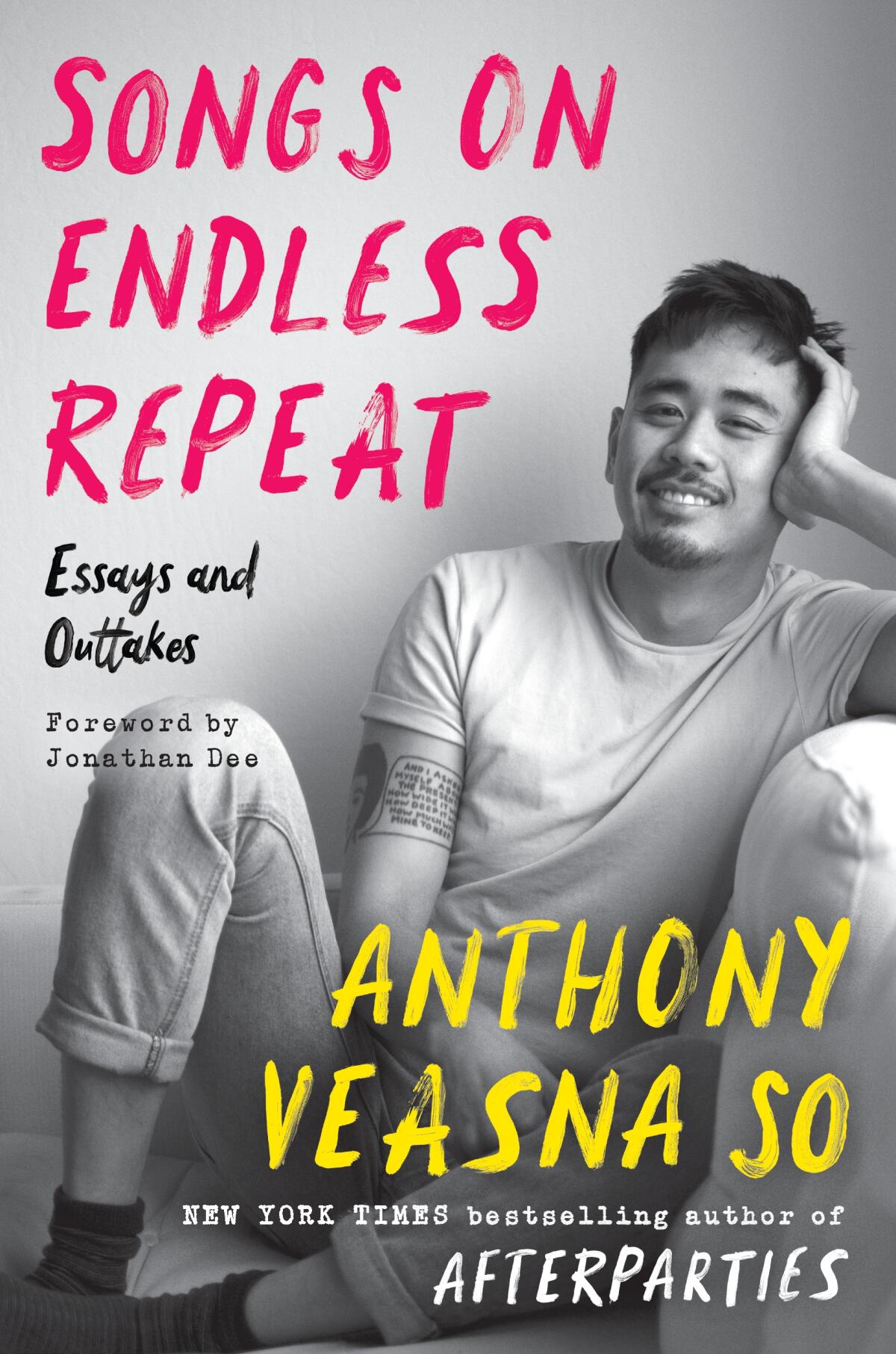

Songs on Endless Repeat: Essays and Outtakes

By Anthony Veasna So

Ecco: 240 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Comedy and its epistemological relation to trauma theory” is the proposed dissertation topic of one of the characters in Anthony Veasna So’s new collection of essays and fiction, “Songs on Endless Repeat.” More precisely, the character — a gay Cambodian American languishing in a philosophy PhD program at Stanford — proposes writing about how both comedy and trauma “revel in the fragmentary, broken nature of reality.”

The statement could double as an oblique description of So’s own work. His debut collection, “Afterparties,” published after his death in 2020 from an accidental drug overdose, showcased his considerable talent for vivifying members of the Cambodian community in Stockton. Many of the characters either survived or were direct descendants of those who survived the Khmer Rouge regime, which killed anywhere from 1.5 to 3 million people.

Friends and family mourn Anthony Veasna So, whose highly anticipated debut story collection, “Afterparties,” brings refugee Stockton to life.

Survivor’s guilt is too pallid a phrase to describe what many felt in the wake of Pol Pot’s senseless slaughter; the best that many of So’s characters achieve is a “fragmentary” existence, living on the ledge between two worlds. Yet So’s writing is nothing if not funny. Humor, in his work, is never far from horror — may indeed be the coinage of a horrified brain. His sentences are full of nervy energy and irreverent wit: highly medicated patients at an elder care facility produce “mutant” excrement; a badminton coach past his prime looks like “Bruce Willis in yellow-brownface”; a nouveau riche character’s designer handbags are “so giant I swore they had gained consciousness and could swallow me whole, were I to transgress their master.”

“Songs on Endless Repeat,” which collects shards of So’s unfinished novel, “Straight Thru Cambotown,” as well as assorted essays, displays many of the same coruscating traits as “Afterparties”: a pitch-perfect ear for dialogue, a knack for pungent prose and a large-hearted capacity to commune with people across what So calls the “Cambo proh racial complex spectrum.”

Roughly half the book consists of chapters from the novel-in-progress. As in “Afterparties,” the death of a character serves as the pneumatic spark for familial reunification. Peou, who dies in a car accident, “considered her real talent to be in always knowing, to the finest degree, how much people owed her.” Her head for numbers enables her to become the “Counter” of the “Circle of Money,” or a kind of loan officer for the tight-knit Cambodian community in Los Angeles County that residents think of simply as “Cambotown” — the area that “sat under South Los Angeles and Compton, flanked on either side by Torrance and Westminster. Peou is the “red-hot center of Cambotown”; her sudden death causes tectonic shifts in the power structure.

The strongest story in the collection focuses on Darren and Vinny, two of Peou’s nephews. The cousins made a pact when they were younger to do “something legit with our lives.” When they meet up again after Peou’s death, several years have passed and their paths have diverged: Darren, a kind of surrogate for So, is a dejected graduate student at Stanford studying comedy instead of performing it; Vinny leads a flamboyant life as an underground rapper.

Long Beach-born Cambodian American painter Tidawhitney Lek has canvases on view in the Hammer’s biennial and a solo show at the Long Beach Museum of Art.

The chapter, narrated in a close third person, packs several dissertations’ worth of material on being Cambodian into short, punchy paragraphs. A younger Darren regularly introduced himself at open-mic night thusly: “I’m off-brand Asian, you know? I have less in common with mainstream Asians, like Chinese, Japanese, the usual suspects, than, say, middle-aged Jewish people, because — and let me be real with you for a second before I start talking boners or some s— — both older Jewish folks and young Cambos have parents who either survived or died in a genocide!”

The “off-brand” line appears elsewhere in “Songs” and also in “Afterparties.” Yet on almost every page, there’s fresh writing to marvel over. In his introduction to the collection, Jonathan Dee, a novelist and one of So’s mentors at Syracuse University, where the younger writer earned his MFA, aptly remarks that “every sentence seems at its observational bursting point.” One character’s eyebrows are “an attack of angles”; another character has a “droopy face creased with lines like crooked canals meant to drain his large, sullen eyes of life.”

At the time of his death, So was that rarest of species: not just a novelist, but a formidable critic. Many of the essays collected in “Songs” were previously published in outlets like n+1, the New Yorker and Ninth Letter. He captures, with effortless eloquence, the double-bind of being an Asian American. His writing on everything from “deep reality TV” (an oxymoron?) to book-skimming as a flaneurish “mode of aesthetic encountering” is laced, as always, with humor. In one representative passage, So half-seriously, half-facetiously writes that Maddox Jolie Pitt, Angelina Jolie’s adopted son, is his “role model, because I’m still waiting for a rich white person to adopt me.”

The sampling of his nonfiction also allows us to catch glimpses of the autobiographical well from which So drew material for his fiction. When he writes, in the story “Peou and her Kmouys,” that some Cambo families “use a fake address so [their children] can attend the magnet K-8 school in the good district,” that detail is lifted from the milieu he describes in his essay “Manchester Street.”

The Man of Two Faces returns in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s ‘The Committed.’ The author explains what’s different.

Glorious as the essays are to read, those already familiar with his nonfiction may find themselves, like me, impatiently flipping ahead to the fresher quarry of So’s novel, which is unwisely chopped up and slotted in between sections of nonfiction. The choice to alternate sections of fiction and nonfiction was made, Dee notes in his introduction, so as to stage a kind of dialogue between his two kinds of writing and to reveal the permeable boundary they share. It strikes me as an unnecessary move, just as the labeling of pieces as “fiction” and “nonfiction” under each chapter title seems superfluous.

What makes it unnecessary is exactly the fluidity with which the author moved between these modes, almost rendering such divisions obsolete. As he writes in “We Are All the Same Here, Us Cambos”: “It’s easy to think we have the same story. We do, and we don’t.”

Feng is a freelance critic in Washington, D.C., whose writing has appeared in the TLS, 4Columns, and the New York Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.