On the Shelf

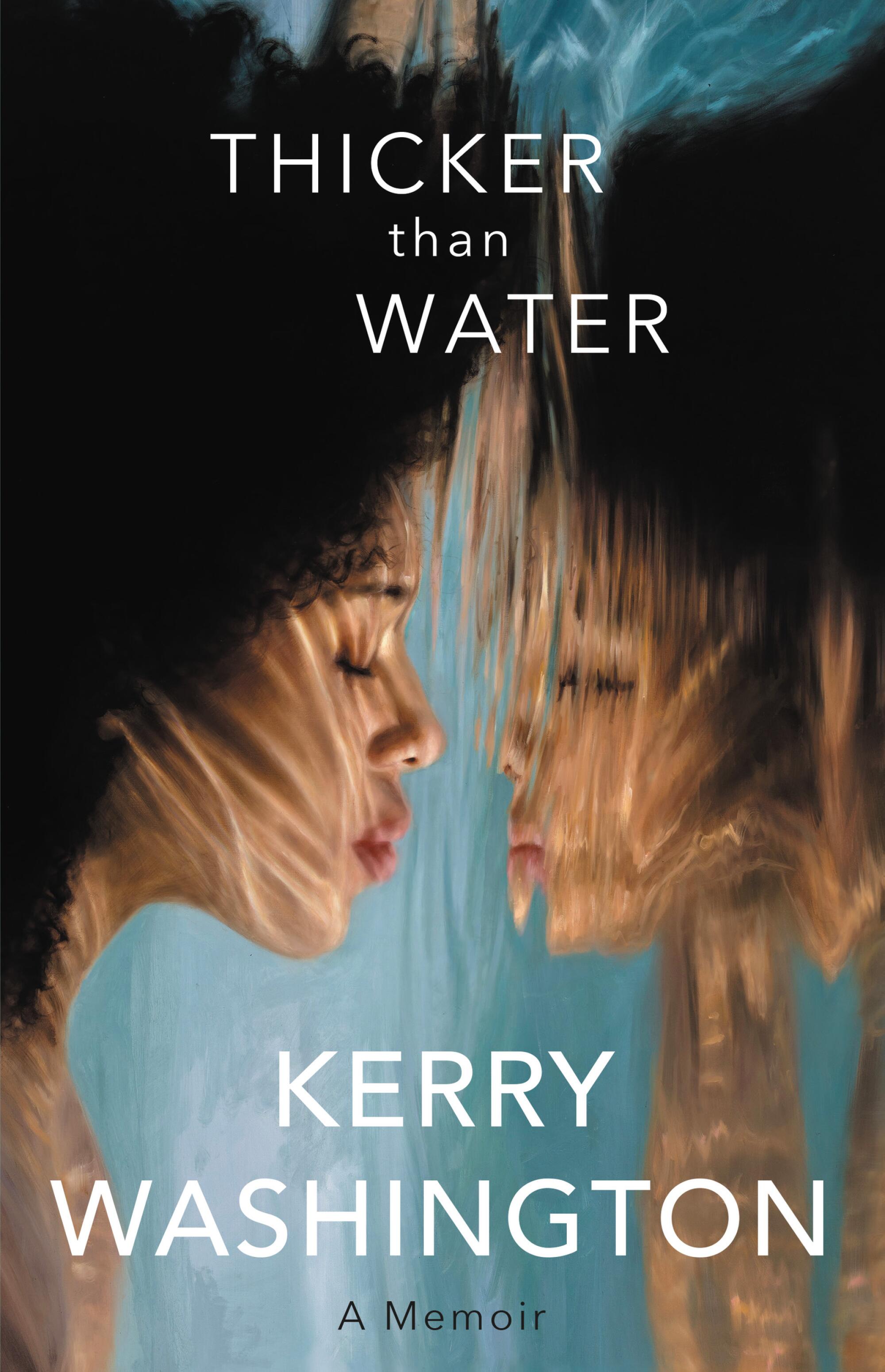

Thicker Than Water: A Memoir

By Kerry Washington

Little, Brown Spark: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Kerry Washington feels the most beautiful when she’s underwater.

She felt this way even as a child, whether swimming in the pool at her apartment complex in the Bronx, in a lake or out in the ocean. She would imagine herself as a mermaid, able to exist anywhere.

“I think I feel most beautiful now, in addition to being in water, with the people that I love most when I’m imagining myself through their eyes,” she said during a recent phone interview.

Shortly after she wrapped her groundbreaking role on the ABC hit drama “Scandal” as crisis fixer Olivia Pope, Washington found herself forced to reexamine who she’d imagined herself to be. Her parents sat her down for a conversation, during which they revealed that she had been conceived using a sperm donor.

The actress explains why the play was perfect for her after “Scandal,” which she called “a fairy tale of interracial love,” and defends its controversial walk into a social justice minefield.

This new information helped shape Washington’s new memoir, “Thicker Than Water,” out this week. The book is her way of embracing the many truths about herself: the unexplained disconnect she felt with her parents, perfectionism, panic attacks, sexual trauma, body image issues and the search for solace, sometimes in food, drug use or alcohol.

The memoir also chronicles Washington’s rise to Hollywood fame, from her early years in films like “Our Song” and “Save the Last Dance” to roles in “Ray,” “The Last King of Scotland,” “For Colored Girls,” “Django Unchained” and the HBO movie “Confirmation” (as Anita Hill), the TV superstardom that came with “Scandal” and the launch of her production company, Simpson Street.

Washington’s conversation with The Times, about what it’s meant to be seen in a bigger way and what she’s saying no to these days, has been edited for clarity and length.

What compelled you to tell your story now?

I had been thrown into this new journey of who I am and what I believe in, in just everything about how my life had turned out, and I had a hard time writing about it then.

I have been private about my personal life and very protective of my children, but my parents have always been a part of my public narrative. And so suddenly, when I got this new information, I felt like a fraud. I felt like if I wasn’t telling the truth about my parents, I was going to perpetuate a lie. I didn’t want to hide from my story, and if the story was going to be out in some way, I wanted to be in charge of my story.

What was going through your mind when you told your parents what you were going to write about?

We went into family therapy together for a little while; we really just started engaging with each other with a lot more transparency and directness and honesty. I don’t remember exactly how I told them. The culture of secrecy, rejecting the truth or even resisting it, has really dissolved in our family dynamic, which is a beautiful thing.

In her two latest projects, ‘American Son’ and ‘Little Fires Everywhere,’ Kerry Washington confronts painful truths.

Black women often feel pressure to be hyper-competent — to be the best they can be for everyone around them. How do you think we can step back from that mind-set?

There are so many forces that force us into feeling like we had to be twice as good, and I think the way we have to step back is to try to really hold on to our humanity. I’m probably now navigating hyper-competency more than perfectionism, because I learned how important it is to make mistakes and take risks. But I think when I was younger, I was really, really afraid to not get everything right because I believed so much more in the illusion of control: that if I could do it perfectly that I could avoid the pain of mistakes or rejection.

How do you feel you’re holding on to your humanity these days?

Writing a book is a real practice in affirming my humanity. A lot of my work revolves around: Every single one of us matters. In the political space, a lot of the work I do is supporting grassroots community organizations and telling them that they are the Olivia Popes of their neighborhoods, they are the people who have power in the community by showing up. And then on the narrative side of Simpson Street, we’re so invested in upending otherness and what protagonists look like.

And in a lot of ways, this moment of me taking the time to figure out what my story is: Can I allow myself to be the protagonist of my life, rather than [in] the story my parents are telling or [as] a supporting character in other actors’ lives? Instead of pouring myself into other people’s lives, can I honor having my own value? I find enormous gratification being the supporting character in other people’s lives, other writers and producers and actors, or in my husband’s story, my children’s story. All of those roles are so important to me, but being a supporting character needs to be a choice.

You’re someone who has been on screens and stages for some time now. When do you feel most seen?

As I talk to people who have read the memoir, the biggest reaction that’s been so fascinating, and it’s been an unexpected honor, is when people read the book, they tell me their secret. There is healing in the sharing of secrets, in the shedding of that shame. There’s so much opportunity for community and I feel so seen, because when somebody shares their vulnerability with me, to me that is a signal that they have really seen me and in seeing my vulnerability they feel safe to share.

When mega producer Shonda Rhimes— such a proponent of saying “yes” to new experiences that she wrote a book on it — asks if you want to direct one of the final episodes of a groundbreaking TV series, there’s really only one suitable answer.

What were you most scared of sharing in this book?

All of it — and sharing different things to different people. The biggest hurdle was handing it to my parents. Once they read it, once they gave me their blessing, I felt like I’m OK.

You found yourself learning from and pouring the emotions you couldn’t always feel in your personal life into your acting roles. Has that shifted for you?

In some ways it’s with more intensity. There’s been a liberation with learning more of the truth about myself that’s allowed me to pour more of myself into the work. It’s just more freedom, more willingness to take risks and dive deep and take bigger swings and digging for more truth. It’s more creative courage.

What are you saying no to more of these days?

I guess I’m saying no to old patterns of ignoring my intuition. I’m saying no to any kind of internal disconnect, because I think in a lot of ways when my parents gave me this information it was an invitation to turn to myself again. I had had these intuitive inklings that something was being withheld from me and something was off. There was always this sense of knowing that I was kind of cut off from. When I got this information from my parents, it was a confirmation that I’m not crazy and about my own sense of knowingness.

Kerry Washington will appear at the Palace Theatre for a conversation about her memoir with Gabrielle Union on Oct. 1. Get tickets here.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.