How the AR-15 became America’s most popular and deadly weapon

On the Shelf

American Gun: The True Story of the AR-15

By Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson

FSG: 496 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar. But sometimes a semiautomatic rifle is much more than just a killing machine.

“It’s stunning how the AR-15 has come to symbolize so much in the country’s culture wars,” said Zusha Elinson, who, with fellow Wall Street Journal reporter Cameron McWhirter, wrote the new object history “American Gun: The True Story of the AR-15.”

The two journalists, who recently spoke together with The Times by video (McWhirter from the Atlanta suburbs, Elinson from the Bay Area), started writing the book after covering a barrage of mass shootings.

“We’ve stood in these places surrounded by blood and the question kept popping up about whether an AR-15 was used,” McWhirter recalled. “The gun had become a symbol for the gun control debate.”

Gun control advocates and California officials condemned the ruling, saying it could touch off a broader push to weaken firearm laws.

In recent years, Elinson added, the weapon has become a talisman of a yawning political divide. “It now stands for a lot more than just gun rights, it stands for a host of libertarian and conservative values,” he said, pointing to the growth of the Black Rifle Coffee Company, the Starbucks alternative for conservatives, and the sudden surge last winter of far-right members of Congress wearing AR-15 pins.

McWhirter said the book aims to give people an understanding of how we reached this impasse: “When we started looking into it, we realized the gun has a fascinating history going back to the Cold War that no one really knows.”

It starts with Eugene Stoner, a Marine veteran obsessed with solving engineering problems, who spent much of the 1950s designing guns. And it’s a classic inventor’s tale, as he gets taken by an unscrupulous business partner and repeatedly bumps up against the military bureaucracy.

He engineered the now iconic weapon for a company called ArmaLite (which is where the AR comes from) but did much of his best work in his Westchester garage; he was relentless, always drawing on napkins and even tablecloths in fancy restaurants (to the chagrin of his wife).

The military-style rifles used in some of the deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history, including Sunday’s massacre at a gay nightclub in Florida, have become increasingly popular in recent years among American consumers.

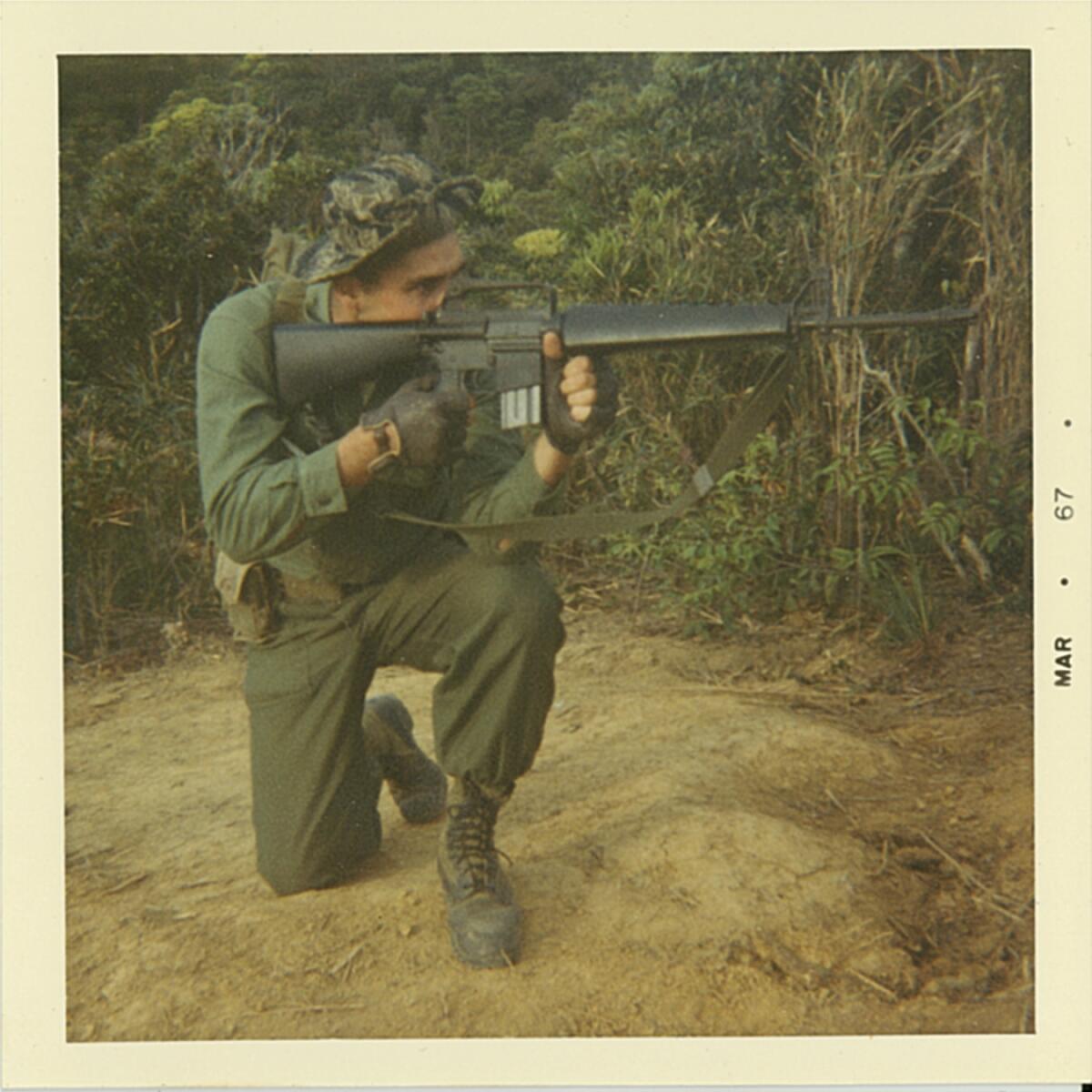

ArmaLite eventually sold the rights to Stoner’s AR-15 to the Colt Firearm Company; after a fair bit of rejection and political infighting, the U.S. military adopted the gun, rebranded the M16, as a standard weapon during the Vietnam War. The Army, however, made ill-advised changes that caused jamming and led to American soldiers getting killed before an investigation led to improvements.

Later, the civilian version found its way into American homes; decades later, assault rifles became commonplace at mass shootings.

“This gun has had a life far beyond what Stoner ever would have envisioned,” McWhirter continued. “Stoner created something for the military, but you jump ahead to Jan. 6 and people are waving the AR-15 in defiance of the federal government, with flags declaring, ‘Come and take it.’”

Stoner was intensely apolitical but a 2nd Amendment believer; he was proud of inventing the M16 but uninvolved in the debates over the gun’s civilian usage. McWhirter pointed out that when Stoner died in 1997, three years into America’s short-lived assault rifle ban, none of his obituaries mentioned the AR-15.

And yet it was Stoner’s craftsmanship that made it so adaptable. The gun’s strength in combat — it’s light, allowing soldiers to carry more ammunition, and it sprays bullets, obviating the need for precision — make it “the perfect weapon,” McWhirter said, “for someone who has never fired a gun before to walk into a school and kill a lot of people within minutes.”

Two women killed in a shooting at the Beyond Wonderland music festival in Washington were from Southern California. They had just become engaged and moved to Seattle.

The book recounts some of the worst mass shootings, from the Las Vegas concert to the Aurora, Colo., movie theater to Sandy Hook elementary school, through the eyes of people who lost loved ones as well as survivors; one powerful chapter focuses on Valerie Kallis-Weber, who suffered horrific physical injuries in the 2015 San Bernardino shooting.

But beyond an individual’s pain, McWhirter said the echoes of a single mass shooting ripple through entire communities. “They cause trauma in society.”

Elinson noted that while assault rifles cause a tiny fraction of the mayhem wreaked by guns in America, mass shootings carry a greater weight than a simple death toll.

“[They] terrify people in a way that everyday murders do not because they make us feel unsafe in public places,” said Elinson. “They have the same effect as terrorism. You have full security apparatuses set up to defend against them and schoolchildren across the country drilling to prepare for them.”

The reporters secured in-depth interviews and documents from Stoner’s family, who had rarely spoken publicly; they also fired and even purchased AR-15s.

They did not want the book to be prescriptive. “I’m not that interested in my own opinions anymore,” Elinson said. “We are interested in what the story is and what the reality is.”

Still, after delineating how AR-15s became what McWhirter called a “political and cultural chew toy that the two sides are constantly tearing at,” they explore potential compromises and solutions.

Ioan Grillo’s “Blood Gun Money” traces the escalating drug wars in Latin America to the “iron river” of automatic weapons from the tragically lax U.S.

Australia banned all assault rifles in the 1990s and has been free of the mass shooting plague since; Congress created a loophole-riddled ban that lasted only 10 years. The 1994 ban was destructive politically, as many gun owners felt the government was overreaching and blaming the responsible majority for the disturbed exceptions.

“Until that time the AR-15 had meant barely anything to anyone, but that’s a key moment where the AR-15 became this symbol of 2nd Amendment rights and created this division,” said Elinson. Many hunters and gun collectors initially disdained this somewhat flimsy and imprecise weapon, he added, but then flocked to it in the spirit of rebellion.

“There are a lot of gun owners who handle AR-15s responsibly,” said McWhirter. “The problem is that people who are disturbed can get one easily and cause a lot of damage.”

1

2

There were about 400,000 AR-15-style guns prior to 1994; today there are 20 million in America. Given that growth, the authors scoff at the Biden administration reviving talk of a ban.

“It’s just not feasible unless you’re going to go house to house,” said McWhirter. The duo explore ideas that might reduce the number of tragedies: taking guns away from dangerous people, raising the legal age for owning an assault rifle from 18 to 21, requiring registration and lengthy background checks for these powerful weapons, banning high-capacity magazines.

Some of these measures have support even among pro-gun advocates, said Elinson, but McWhirter acknowledged that all the solutions require compromise, which is “not a very common political trait right now in America.”

The book ends with a chapter titled “What Would Stoner Do,” which is fitting because the authors want to take these ideas into a metaphorical version of the inventor’s garage. “We have to stop thinking like conservatives or liberals and instead think how an engineer like Stoner would,” said McWhirter. “How are we going to solve the problem?”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.