Why bring a child into this broken world? Take an Antarctic expedition to find out

Review

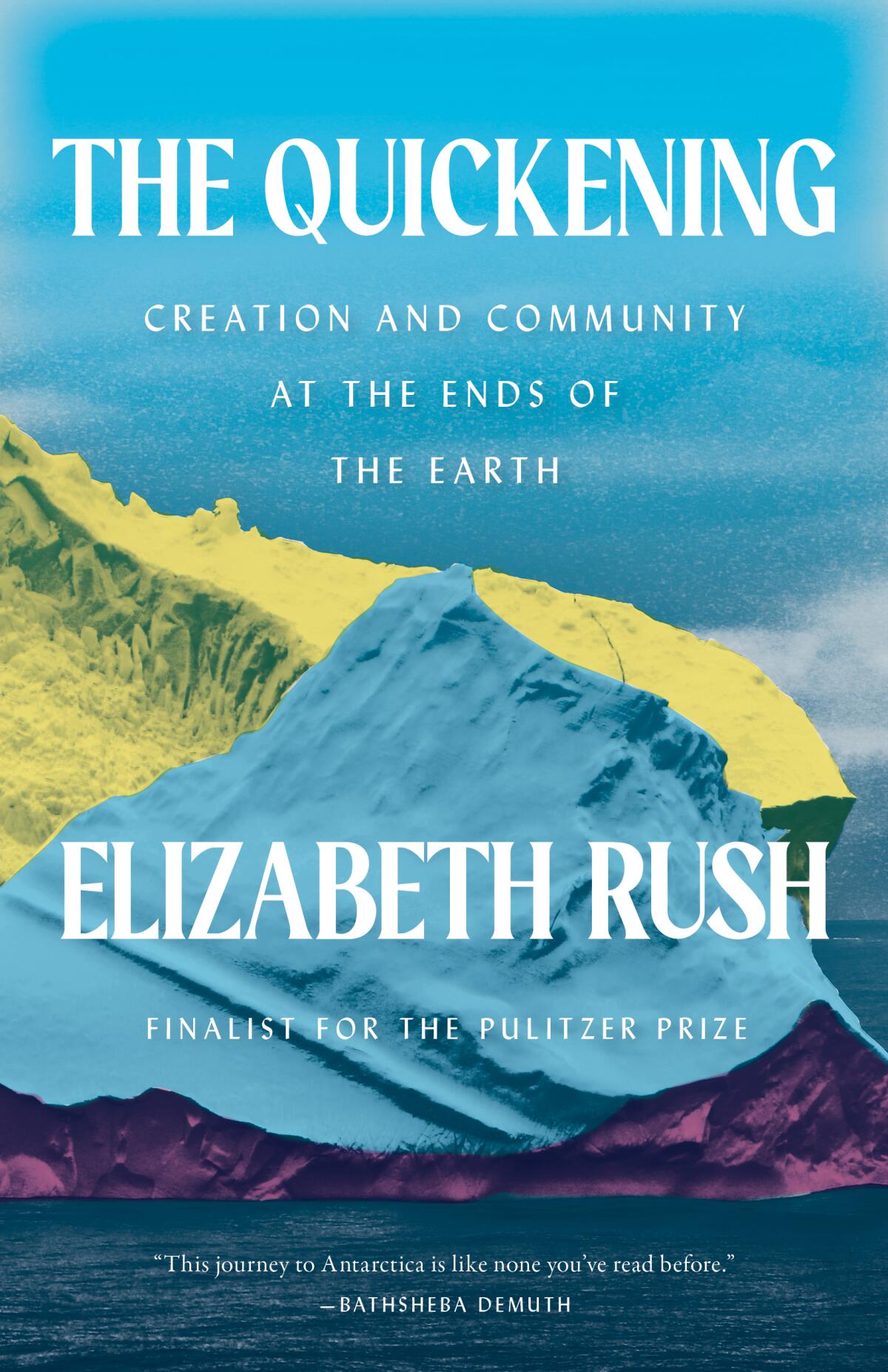

The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth

By Elizabeth Rush

Milkweed: 424 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We have long spoken of journeys to the poles as going “to the ends of the earth.” But what if a voyage to Antarctica takes us to beginnings? What if it isn’t so much an exploration of outer limits as a chance to rethink the core of our existence? “The Quickening,” Elizabeth Rush’s new work of nonfiction, reframes the end of the world — geographical and climatological.

Perhaps the prospect of reading another book about the ways we are destroying our ability to survive on Earth fills you with dread. I admit to my own hesitation, but “The Quickening” instead filled me with hope. It turns out our bleakest continent is not merely a site to plant a flag and prove one’s mettle, but also a place for collective action to repair a breaking world.

Rush, whose previous climate book, “Rising,” was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize, offers a corrective to the way “Antarctica has long been used” — as a springboard for narratives that “encourage competition over collaboration” and suggest “that victories are achieved single-handedly through genius and muscle and will, not through months and years of dogged work by the many.”

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

The writer’s task is to chronicle an effort of the latter kind, the expedition of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer from the tip of Chile to the vast and vulnerable Thwaites Glacier. The goal of its research team is to gather samples and data from a mass of ice so large that if it alone were to melt, ocean levels would rise by two feet. The untrod glacier is made accessible only by the damage already done to the enormous ice sheets that cover the continent.

Alongside recitations of the science as well as meditations of a much more personal nature, the intrepid reader is treated to prose that lifts Rush’s work far above standard journalism. “Here,” she writes as the ship draws closer to the icy continent, “where certain colors begin: apricot, lemon curd, rose hip, nectarine. All are born in this jam-smudged southern sky.”

Rush both argues that a reclamation is underway. Our understanding of Antarctica, she writes, has been “dictated by the questions humans have chosen to ask, questions that are shaped as much by the pressing concerns of the day as they are by the culture of the geophysical sciences, which for most of the last two centuries was also a man’s domain.”

Present-day researchers — an increasingly diverse lot — are now asking different questions than the adventurers did, though these are often still driven by what the land can do for us. But what if we could think of the land as a little-understood system that could provoke us to find better questions?

Pioneers such as forest ecologist Suzanne Simard have argued that framing the natural world through models dictated by competition rather than collaboration has led us to where we are now. Our paradigms need to shift in order to see that, like communities, ecosystems are not arenas of mortal combat but rather networks that create space for all. When these systems get out of balance — as when we dam a river or plant extractive monocultures or send tons of CO2 into the atmosphere — destruction follows.

In a climate crisis that feels huge and hopeless, these eight books — essays, fiction, memoir and poetry on the wild — will help you focus on small things

Rush argues that capitalism is the force behind our indifference to systems. One of the worst examples she cites is the way British Petroleum shifted the burden of climate change onto the shoulders of individuals. In 2005, BP created a $100-million media campaign that introduced “carbon footprints,” propagating the idea that only personal choices — whether to fly, drive, compost or have children — can prevent disaster.

This makes climate change an individual failure, rather than the global problem it is. But where Rush sees destruction, she also sees hope — the chance to create networks of cooperation that can replace the old, exhausted paradigms.

The journey of the Palmer is a case in point. The quarantined world aboard the ship, with its 57 passengers, becomes, in Rush’s fine telling, a collaborative model. Those aboard represent multiple continents and include 16 women, making it conducive to new ways of thinking. (Once infamously referenced as “the womanless white continent of peace,” Antarctica was largely closed to scientists of color and women.) Because of this unique chance to view Thwaites, multiple competing research teams coalesce into a community whose cross-disciplinary interests form a hive of creativity.

Rush also heads to Antarctica with a pressing personal dilemma. As a writer whose work encompasses threats to survival, she struggles with her strong desire to become a mother. Should she accept that the Earth cannot hold one more being, or is individualizing a global problem only feeding into BP’s capitalist narrative? Boiling down the climate crisis to a childbearing decision, particularly in a memoir by a woman, might risk reinforcing gender stereotypes. But onboard the ship this question doesn’t seem essentialist: It feels essential, maybe even existential.

Rush has proven the power of individual change in one sense — by writing “The Quickening.” For much of its history, Antarctica has been regarded as a frozen rock whose function was to aid in territorial conquest. Then it was seen as the place that would show us the history of the Earth. Rush recasts it as a place that, by supporting teamwork and offering clues to climate survival, has much to teach us about the future.

The 14 most essential works of nonfiction include histories by Kevin Starr, Carey McWilliams, Reyner Banham and, ruling them all, Mike Davis’ ‘City of Quartz.’

In a remarkable passage — a section preamble narrated in the third person — Rush writes:

“Never before has a human being set eyes on any of this. ... She tries not to ask [her shipmates] how they feel about being here, because she suspects that they, like her, haven’t got it quite sorted yet. Are they discovering someplace new or drowning in it? Nothing about the last continent is clear, though she thought the ice would sharpen her understanding of whether they stand at the end of the world or the start of a new one.”

These are not the outer limits. This is where we all are today.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.