Think you’ve had enough Jane Austen remakes? This novel will make you think again

Review

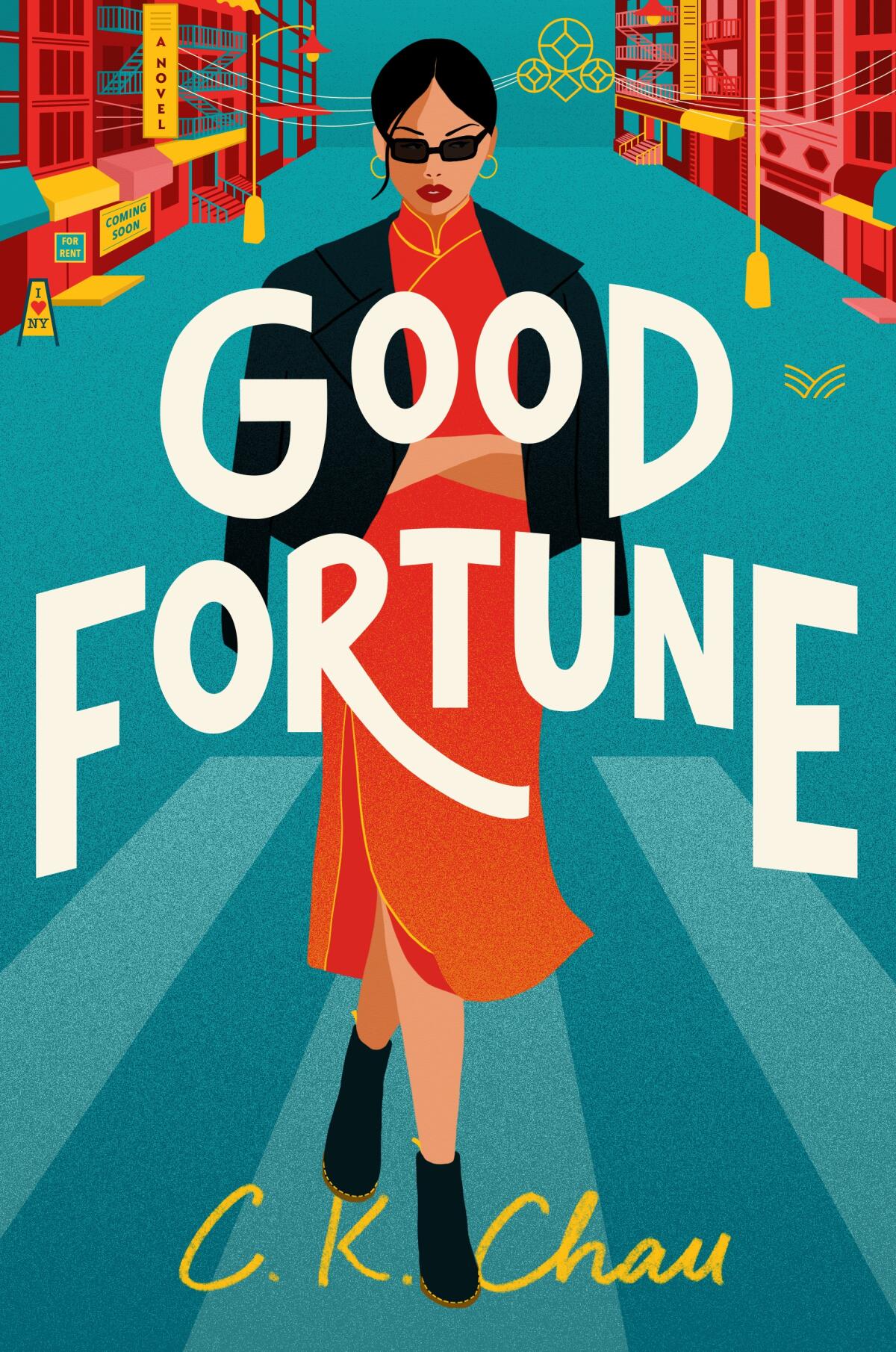

'Good Fortune'

By C.K. Chau

HarperVia: 416 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There have been dozens, and probably even hundreds, of adaptations of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice.” From faithful BBC miniseries to jokey zombie mashups, from relatively obscure genre mystery sequels to blockbuster vampire romances, there is a “P&P” for every taste and subgenre. Do we really need more?

C.K. Chau’s wonderful debut novel, “Good Fortune,” makes a strong case that we do. Chau airlifts Elizabeth and Darcy from early 19th century England and sets them down in New York’s Chinatown in the early 2000s. The venue change is fun. But what really makes the novel work is that it functions as both tribute and gentle critique of its blueprint. The novel implicitly questions “Pride and Prejudice’s” snobbery and highlights the ways Austen took part in the class prejudice she was, to some extent, questioning.

Chau’s plot closely follows Austen’s. Elizabeth Chen (affectionately called LB in this version) has an older, sweet-tempered sister, Jane, three younger, sillier sisters and a chattering, social-climbing mom (here named Jade). LB has few prospects — and certainly is not interested in pompous developer Darcy Wong, who is as supercilious as he is wealthy.

Directed by Autumn de Wilde and starring Anya Taylor-Joy, this latest version of “Emma,” Jane Austen’s beloved novel, lives up to its predecessors.

The outlines are familiar, but the details are tweaked in important ways. Austen’s Bennet family is shabby upper-middle-class gentility. They have a comfortable home and a life of comfort, though without an inheritance the sisters have little hope of a decent future if they don’t marry well. As such, the Bennets are determined to maintain their current status; the loquacious Mrs. Bennet is outraged when a guest suggests the meal they’re eating was cooked by her daughters rather than a servant.

The Chens, in contrast, are barely holding on to lower middle class. Father Vincent is the manager of a takeout joint called Lulu’s because he couldn’t get together the capital to purchase his own restaurant; the sisters take shifts helping out. Mother Jade has almost but not quite gotten her Realtor license. The family lives “seven in a two-bedroom in a fourth-floor walk-up with leaking pipes, flaking paint, inconsistent heat, quarrelsome neighbors, and a landlord who remembered them only when the rent was due.”

Austen loves to show the poor manners of the Bennets; she lampoons Mrs. Bennet for her marital aspirations for her daughters and sister Mary for her grotesque efforts to appear knowledgeable and cultured. The Chens, buried much further down in the social heap, are correspondingly more desperate to scramble out. Jade has elaborate dreams, “And what burdens those dreams were! Money, success, happiness, and Chinese husbands, to name a few.”

Mrs. Bennet never works a day in her life; Jade bathes in the grease fat of trade. The novel opens as she tries to convince the wealthy Hong Kong Wongs to invest in the dilapidated local community center — and to wheedle out of them a substantial finder’s fee to which she has, at best, a tenuous claim.

‘Fiona and Jane,’ Jean Chen Ho’s collection of stories, pays homage to friendships complicated by displacement, sexuality and the passage of time.

Jade’s grasping feels more reasonable than the Bennets’ in light of the Chens’ proximity to poverty: What mother wouldn’t be concerned for their future? She badgers LB to get a job and despairs when her stubborn daughter holds out for meaningful work rather than going to Scranton, Pa., to work in collections. But when someone else — even the imposing Darcy! — criticizes Jade’s clan ... well. You can hear the “record scratch as Jade drew back in her seat,” Chau writes. “Any insult to home, husband, or her daughters was a declaration of war.”

Jade has a right and a backbone — which makes you wonder whether Mrs. Bennet didn’t maybe have a right and a backbone too. Was she so silly and empty-headed after all?

If Mrs. Bennet starts to look a little more heroic in light of Jade, Elizabeth looks somewhat less so in comparison with LB.

It’s true that LB isn’t as scintillatingly witty as her predecessor. (Chau can’t compete there with Austen — but who can?) And yet, LB has a conscience and a passion that stand her in good stead. She’s fiercely committed to keeping the center as a community resource, rather than turning it into upscale housing or shopping. She’s got a calling for photography, which she works at seriously — unlike Elizabeth, who almost boasts of her indifferent attention to the piano. And LB relishes her role as big sister and surrogate mom.

The modern version is embedded in her community and family; she’s proud of being “the next in a long line of people who worked to get by.” That’s a jolting contrast to Lizzie Bennet, who is distinguished not because she’s committed to her milieu but because manners and common sense set her apart. Austen (and Darcy) love Elizabeth because she rises above her situation. Chau (and her Darcy) love LB because she doesn’t want to rise unless she can take everyone with her. “They could keep their money, their attention, their pristine reputations,” LB muses acidly; “she’d take a greasy day at Lulu’s shooting the s—.”

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

Chau isn’t the first to explore and question Austen’s class assumptions. The best-known example is probably Jo Baker’s 2013 novel, “Longbourn,” which chronicles the hard and often joyless life of Sarah, one of the Bennets’ housemaids. “Longbourn” is a bleak, painful novel about exploitation and drudgery, deliberately eschewing Austen’s light humor. But, as different as “Pride and Prejudice” and “Longbourn” are, they agree in finding little room for laughter and romance in stories of the lower class.

In “Good Fortune,” however, working-class life is neither pure misery nor set dressing: It is companionship and solidarity, and it is a narrative engine. In re-classing the Bennets, Chau both uncovers new layers in the original and reveals some of what Austen left out. “Where we come from is as important as where we want to go,” a chastened Darcy admits to LB. That isn’t really the message of “Pride and Prejudice.” But it’s Chau’s good fortune, and ours, to see in this adaptation not just Jade’s foolishness, but also her courage and love.

Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.