Books about books are catnip for avid readers. This week there’s a bumper crop

On the Shelf

Assessing the new crop of books about books

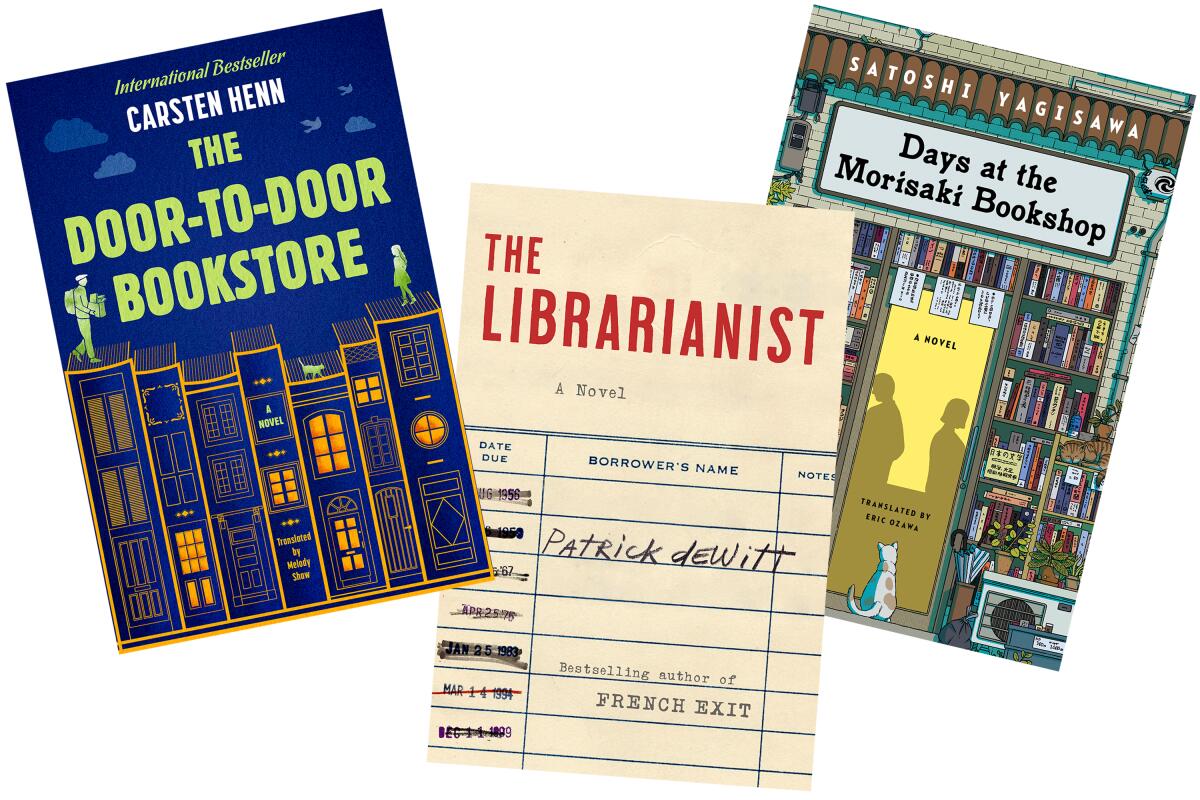

The Librarianist

By Patrick deWitt

Ecco: 352 pages, $30

The Door-to-Door Bookstore

By Carsten Henn

Hanover Square: 240 pages, $29

Days at the Morisaki Bookshop

By Satoshi Yagisawa

Harper: 160 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Directors love movies about filmmaking; songwriters’ lyrics are often about music. So it’s only natural that authors often muse about books and the business of distributing them. (And that book distributors rightly expect readers to lap them up.) The Fourth of July adds three new titles to bookshelves — “Days at the Morisaki Bookshop,” “The Librarianist” and “The Door-to-Door Bookstore” — that focus to varying degrees on the delights of books and reading, though all hold appeal for book lovers.

In part, that appeal is in the atmosphere: Satoshi Yagisawa’s “Morisaki” is as steeped in the ambience of a used bookstore as it is in the culture of reading; Bob Comet in Patrick deWitt’s “Librarianist” seems to love the quiet and order of a library as much as any book that might be found there; and Carsten Henn’s “Door-to-Door” revels in the idea of finding the perfect match between reader and book.

All three feature stereotypical bookworms — quiet loners who enjoy walking the streets of their city. But these summer releases also share the paradoxical quality of being light on what you might call bookishness; they offer simple pleasures, minimal conflict and page after page of low-key charm.

With his lackluster, misogynistic new collection “First Person Singular,” Japan’s most famous author proves his cultural reach exceeds his grasp.

“Morisaki Bookshop” is the slightest, checking in at less than 150 pages with minimal plot. (It was published in Japan more than a decade ago and was adapted into a movie there.) It’s also the weakest of the three. Takako, 25, has been coasting through life until she’s jilted by her boyfriend; depressed, she loses her job and becomes isolated until her quirky uncle Satoru invites her to live above his bookstore in Tokyo’s famous book district, Jimbocho, and help out in the shop.

The early pages are bogged down with clunky exposition and clichéd writing (or translating), favoring phrases like “It all began like a bolt of lightning out of the clear blue sky.” Takako also seems annoyingly immature, frequently overreacting to minor incidents. It doesn’t make her an unreliable narrator so much as an irksome one.

Then she falls in love with Japanese literature and opens her mind to the more independent thinking of Satoru and his long-missing wife, Momoko. These two give the book its emotional hook, such as it is. Satoru is the kind of guy who explains his approach to life by quoting a novel called “Confessions of a Husband”: “My boat travels lightly, drifting aimlessly at the mercy of the current.”

It’s ironic that Takako thinks she’s learning so much about life from literature when it’s really spending time with Satoru and Momoko that opens up her worldview. Still, the book’s vibe makes it pleasant company for an afternoon in the park with a snack, though it will still leave you feeling peckish.

The first time I saw Patrick deWitt make a French exit was at a literary conference in Puerto Rico.

“The Librarianist,” the fifth novel from acclaimed Canadian author deWitt, is heartier fare, making decades of Bob Comet come alive — even if they’re relatively uneventful. We meet Bob in his dotage; retired from life as a librarian, he stumbles into a new sense of purpose as a senior-center volunteer. At first, he tries to read to the residents and visitors, but after striking out with Edgar Allan Poe and Nikolai Gogol, he’s asked to just spend time with folks as a pleasant and steadying presence.

He is that for the reader as well. DeWitt wins us over with scenes including one in which Bob and a new friend, Linus, discuss schadenfreude, which Bob believes he has never felt. “This struck him as regretful; was it not a signal he hadn’t lived his life to its fuller potential?”

But seeing Bob come of age as a young man, we learn that is not quite true. His one close friend, handsome womanizer Ethan, is always finding fun and then trouble. Bob gives him “Crime and Punishment” to read but Ethan remains unchanged, and soon after Bob marries Connie, the first woman he has loved, she runs off with Ethan. “The silence he left behind was a wretched creature,” deWitt writes. After tragedy befalls his friend and his ex-wife, Bob can’t help but feel it was deserved.

After this poignant character study, deWitt sends us even further back. Bob, as a preteen, runs away from home. He is befriended by two aging actresses and their dogs. June and Ida are an idiosyncratic and entertaining duo, but since this adventure doesn’t seem to have shaped the Bob we know, and since he fades into the background as the women dominate their scenes, it feels like an odd digression before we return to the aged Bob. Books and reading fade completely from view here, but deWitt’s writing and endearing characters create a memorable world.

The most completely satisfying experience is “The Door-to-Door Bookstore,” a hit when it was published in Germany three years ago. As with “Morisaki,” some translations in the early pages fall flat, and some exposition rings false. It is also relatively slim, but once the story finds its footing, its two main characters spring fully to life.

The 65 essential bookstores of L.A. County: Their vibes, customers, books and testimonies from customers, writers and owners.

Carl Kollhoff has dedicated his life to working in a bookstore and finding just the right book for each customer. For those in his “village of readers” who can’t make it to the shop, Carl makes house calls, strolling the city each night to visit “Mr. Darcy,” “Doctor Faustus” and others he has nicknamed after literary characters.

When he’s talking about books, Carl’s shy, tentative persona slips away; his soliloquy on Alan Bennett’s “The Uncommon Reader” makes you want to head to your local bookstore. And when Mrs. Longstocking daily presents him with a typo she has found, Carl can instantly concoct a humorous definition.

“Frogiveness, derived from frog-I’ve-ness, denotes the path toward recognizing the innermost core of the self,” he opines, for example. “The concept references the fairy tale, ‘The Frog Prince.’ … Behind the concept of frogiveness lies the hypothesis that each person has an inner frog which they must transform with love — a kiss, in the fairy tale — into a handsome prince. The theory first appears in literature in 1923 in Sigmund Freud’s work, ‘The Id, the Frog and the SuperFrog.”

One day, a precocious and assertive 9-year-old named Schascha joins Carl, over his protestations. She’s a nifty sidekick, winning over all Carl’s readers with her unconventional behavior, and she’s astute enough to challenge Carl to think differently about what kinds of books they really need. Carl starts taking more risks and connecting more with his readers. And when his own life falls apart, they rally together.

The relationship between Carl and Schascha, who does her best thinking in bed at night but worries that “there are so many things that just won’t fit into my brain,” is warm and lively. The story is not always light — there’s a man who can’t admit to his illiteracy, a woman trapped by her abusive husband and an outburst of violence against one of the main characters — but it’s always clearly headed toward a happy ending. The meticulously constructed plot, while somewhat predictable, almost has the feel of a fable without ever becoming cloying.

An avid reader will, of course, happily read books that have nothing to do with books and reading, but as beach reads go, these three — especially “The Door-to-Door Bookstore” — offer a specific kind of summer fun.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.