A white author and a Black editor teamed up to write bestsellers. It wasn’t always easy

On the Shelf

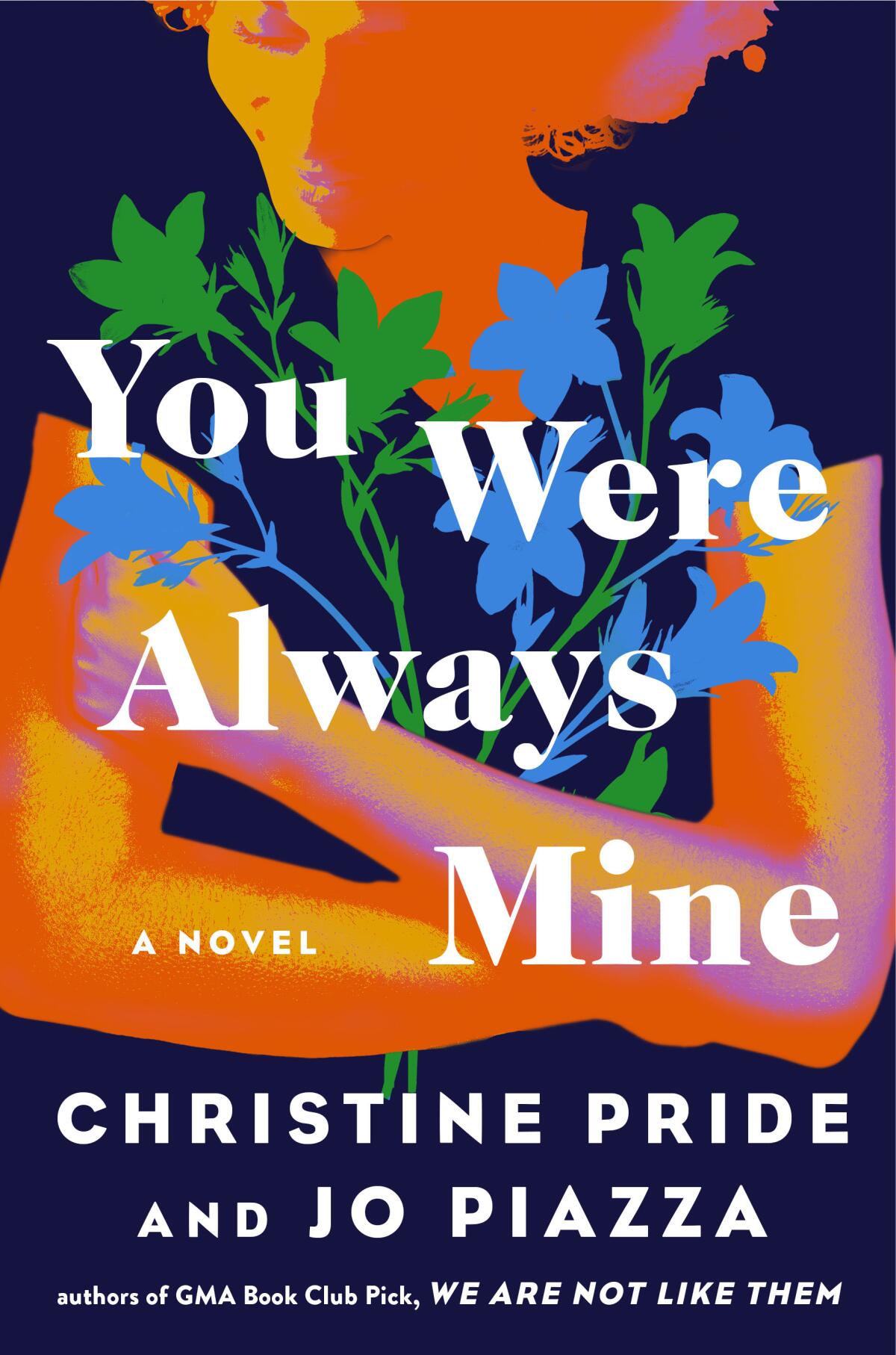

You Were Always Mine

By Christine Pride and Jo Piazza

Atria: 336 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Figaro Bistrot, in the heart of Los Feliz, bustles on a sunny spring morning. Passersby and black-aproned servers squeeze through the maze of sidewalk tables. Working actors and striking screenwriters sip cappuccinos, scowling at stalled-out scripts. Inside, flouncy sconces and antique chandeliers shed flattering light on omelet eaters Insta-posting between bites.

“Cool place,” Christine Pride says, sliding into a red leather banquette. Looking around, she smiles and adds, “I love L.A. It oozes creative spirit. A town built on people telling and selling stories. What’s not to love?”

Willowy, chic and radiating confidence, Pride has sold quite a few stories herself — and told two of her own. For more than 15 years, she was one of the few Black editors in New York book publishing, most recently at Simon & Schuster, where she edited bestsellers by writers ranging from Joy Mangano to Glynnis MacNicol. Her work on Jo Piazza’s novel “Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win” also earned her a fast friend. And it gave her an idea.

T.C. Boyle, Viet Than Nguyen, Rachel Kushner, Carribean Fragoza, Tom Perrotta, Charles Yu, Michelle Tea, Dana Johnson, Luis J. Rodriguez on their pandemic years.

In 2018, Pride gave Piazza a call. “I asked Jo if she wanted to write a novel together, about an interracial friendship that was strained by a police shooting.”

Piazza, a former magazine editor who lives in Philadelphia, told me about her response via email. “I’d co-written novels before,” she said. “I wasn’t sure I’d ever do it again. But Christine had this wonderful idea; a chance to put something into the world that mattered. So I said yes.”

Thus came 2021’s “We Are Not Like Them,” their novel about lifelong besties Jen and Riley — Jen a married, pregnant white woman, Riley a Black TV journalist. The protagonists’ friendship and core beliefs are tested to the breaking point when Jen’s husband, a white cop, is implicated in the shooting of an unarmed Black kid — and Riley is assigned to cover the story.

The authors passed their own test. The novel became a “Good Morning America” book club pick, a Harper‘s Bazaar Best Book Pick of 2021 and sold so well they decided to write a follow-up, “You Were Always Mine,” out this week. Which is not to say there haven’t been bumps on the road — some that paralleled the challenges of their characters.

“Our collaboration,” Piazza told me, “turned out to be more difficult than either of us expected.”

A Black woman and a white woman went viral fighting racism. Then they stopped speaking to each other

A Black woman and a white woman who made a ‘Starbucks racism’ video that went viral joined to combat racism and teach DEI workshops. Now they don’t speak to each other.

At the bistro, over strong coffee and a crisp baguette, Pride provides an example of the co-authors’ challenges. “Jo was frustrated that Riley seemed too perfect, so she offered suggestions for making Riley more flawed and complicated,” Pride recalls. “I took issue with saddling a Black character with stereotypical issues. I wanted Riley to be the rare Black character with a happy middle-class life.”

Piazza explained that her suggestions came from a novelistic impulse: “My intention was to do as I’d done in previous books: give Riley challenges, some of which I’d gone through myself — like parents who went through addiction, teen pregnancy, abortion. I genuinely couldn’t see these issues as being about race — because on some level, everything is about race. That conversation broke both of us down.”

Pride agrees. “It took lots of discussions to get to the other side of that flash point,” she says. “Writing with someone else is incredibly intimate. It requires intense communication. In the beginning of our collaboration, Christine and I didn’t have that language or the shorthand we needed to write together. We almost gave up. But we believed in the story we were telling and the way we intended to tell it.”

The first novel’s reception validated their persistence — and generated the second. Pride, who splits her time between New York and L.A., describes the considerably smoother process that spawned their sophomore effort. “Writing a second book with a partner is a bit like a second marriage,” she says. “This time we each knew what needed to be explained to the other, and how to explain it.”

Just before midnight on a recent Saturday at the headquarters of HSN, the home-shopping pioneer Joy Mangano had a time-sensitive mission.

The dynamic between the second book’s two protagonists is different too, she adds. “For ‘You Were Always Mine,’ we chose the theme of motherhood — one of many ways in which Jo, a white mother of three, and I, a Black woman childless by choice — have had opposite experiences.”

“The differences between us gave us such a wide perspective,” Piazza adds. “What it means to be a mother, what it means to choose to be a mother. Is motherhood a right or a privilege?”

The women in “You Were Always Mine” are 30-something Cinnamon Haynes, a married, Black career counselor in a Georgia beachfront town, and 19-year-old Daisy Dunlap, who shows up one day — and then every day — on the park bench where Cinnamon eats her lunch. Daisy goes missing, leaving a blond, blue-eyed newborn baby and a note for Cinnamon, asking her to raise the child.

Deciding what to do, Cinnamon deliberates with everyone — her husband, her best friend, her minister, the infant she names Bluebell and, of course, herself. These discussions elevate the novel from entertaining domestic drama to enlightening portrait of how race can infuse every decision and interaction, even between close friends.

“The difference between our races gave both books a unique lens,” Piazza says. “Christine hears things in all-Black spaces that I would never hear, and vice versa.”

In ‘All the Sinners Bleed,’ S.A. Cosby takes Southern noir to a new level in the story of a Virginia school shooting that unearths a sinister racist plot.

That lens is evident in a scene in which Cinnamon’s husband, Jayson, is driving them along a desolate road to the beachfront property he has put them into debt to acquire. Cinnamon worries about “white men on horses with torches.” When she searches for Daisy deep inside Georgia’s impoverished white hinterlands and spots “a dusty Corolla with a Confederate flag decal in the back window,” Cinnamon realizes “she has no good sense being out here all alone.”

It’s left to Jayson to articulate the realities of the adoption his wife is contemplating. “I sure as hell don’t think we should be raising a white kid,” he says. “Just imagine me trying to take Bluebell to the playground…I’d end up in handcuffs.” Cinnamon thinks, “Strangers would…think she was a paid caregiver. They’d see him as a criminal.”

Just as Jayson must contend with being pigeonholed, so must his creators. “People put the two of us in a very specific box,” Piazza says. “They assume Christine writes our Black characters and I write our white characters, which couldn’t be further from the truth.”

“We both write everyone,” Pride confirms. “And the characters are better for it, because race is only one dimension of them — and of us.”

Maran is the author of “The New Old Me” and a dozen other books. She lives in Silver Lake.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.