‘I cried a lot for her family’: What it’s like to tell stories of murdered Indigenous women

On the Shelf

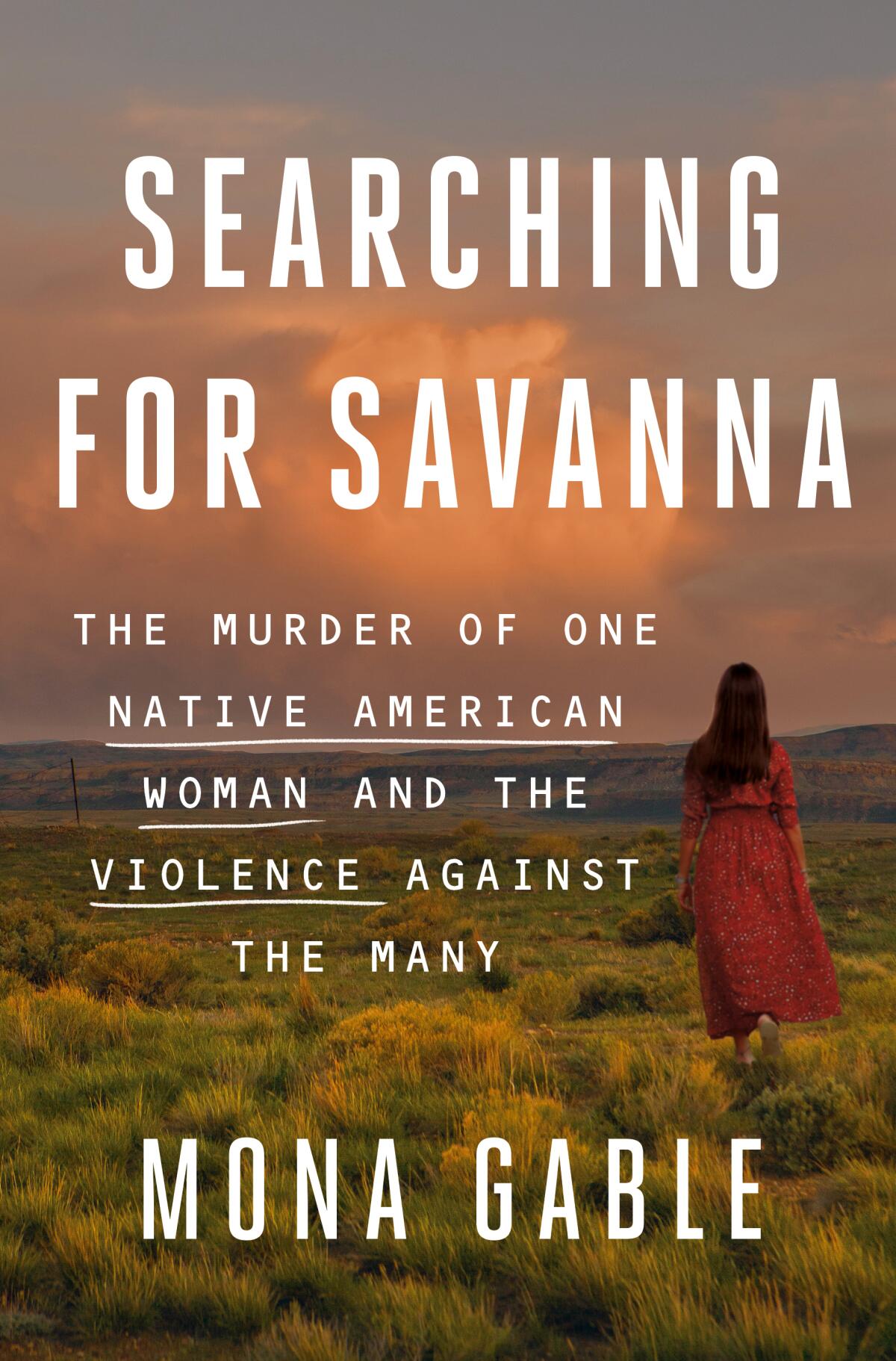

'Searching for Savanna: The Murder of One Native American Woman and the Violence Against the Many'

By Mona Gable

Atria: 320 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“No one knows how many Native American women and girls are missing and murdered each year.” That is the shocking first sentence of Mona Gable’s new book, “Searching for Savanna.” A recent report in The Times, focusing on killings in Northern California that had prompted Round Valley Indian Tribes to declare a state of emergency, cited a federal estimate of 4,200 unsolved cases. The real number could be far higher, and of one thing there is no doubt: The attention paid to this decades-long tragedy is far lower than it should be.

Gable has been writing about gendered violence for many years, and her nonfiction account of the kidnapping and murder of just one of these women — 22-year-old Savanna Lafontaine-Greywind of Fargo, N.D. — chronicles the devastation of her family and her community. Savanna was eight months pregnant when she disappeared after helping her upstairs neighbor with a sewing project. Her body was recovered from the Red River days later.

Gable spoke with The Times on a bright, sunny afternoon at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, digging into the major challenges of pursuing murderers in a community fractured by divided jurisdictions and a legacy of brutal mistreatment.

How did you get interested in Savanna’s specific case?

I was finding out more about my own Native American heritage. I grew up in California, and my grandmother, my dad’s mom who was from the Chickasaw tribe in Oklahoma, died in childbirth. We didn’t really talk about that part of our family for a long time. I came across Savanna’s story in a Fargo newspaper.

The more research I did, the more I saw there were so many of these cases that had never been solved, where women had never even been found. It was shocking to me. There had been some coverage of man camps and how the rates of sexual assault on reservations really skyrocketed. The bigger picture really interested me: Why is this happening? Why do Native American women and girls have the highest rates of violence of any group in the country?

Sasha LaPointe escaped a difficult childhood on a reservation by diving into Seattle punk. Her memoir, “Red Paint,” finds solace in her Native roots.

I read “Highway of Tears” and I was struck then, and I’m struck again reading your book, by how little attention is being paid to this endemic violence against women. Why do you think that is?

I think there’s a few things going on. For most Americans, Native Americans as a whole are invisible, even though 70% of Native Americans live in cities. On top of it, there’s been generations of violence against Native women starting with colonization. It’s been going on forever without any consequences. And there’s just all these cracks in the system where women fell through, and poverty is an issue.

It’s so much easier to make people disappear when people didn’t even know they were there in the first place.

And yet, in the media, when a pretty, blond young woman goes missing, it’s a national headline. Does it make a difference who gets covered?

Absolutely. We know it leads to more prosecutions because resources get thrown into it right away. With Elizabeth Smart, for example, there were a lot of resources poured into finding her. If someone goes missing, you have to start right away or the trail goes cold. And there’s a bias with missing Black and Native women.

Ninety percent of the perpetrators of these crimes are non-Native. When a Native woman disappears, there’s all this confusion about who should look for her because of conflicting laws about who’s in charge of the investigation. So often these things are very slow when a young woman goes missing. Nothing happens right away — law enforcement dismisses these cases as instances of running away — and by the time they take them seriously, the trail has gone cold. Oftentimes, it’s the families who find their relatives [after organizing search parties].

When Savanna went missing, Fargo police responded right away, and they did look for her. But [people did] say, “Oh, well she probably just went for a walk, she’ll be back.” And her family said, “She never goes for a walk by herself. She’s eight months pregnant.” Or they were told, “She’s probably out partying with her friends.” So there’s this sort of attitude that comes into play.

Some true-crime narratives are voyeuristic, and turn murder or rape into entertainment. But your book focuses on Savanna and who she was. What kind of choices as a journalist did you make in writing this book?

I approached Savanna’s family through the prosecutors, who vouched for me. And I understood when they said no. I made sure they knew I wasn’t interested in belaboring the crime and that I wasn’t trying to sensationalize what happened to her. I wanted to know who their daughter was. Gradually they got to know me and began to talk.

In ‘We Were Once a Family,’ Roxanna Asgarian tells the story of the Hart family murders from a crucial point of view: the adopted children’s birth families.

I wasn’t interested in writing something exploitative. I really wanted to expose this problem and talk about it in a small way through one individual and her family and the community she lived in. I also got to know the sort of microcosm of Native American voices who have been advocating for change for many, many years. I just really wanted to give people a picture of Savanna as best as I could. Who was this young woman, and what were her dreams, and what was she looking forward to in life?

You talk about reading her social media. What was it like to reflect on her being gone while reading these posts in which she was so present, sharing these things that were making her happy in the moment?

I cried a lot for her family and her daughter. But I felt this determination once I started reading about her. I felt I was getting to know her, and I wanted her story out there. I wanted people to know who she was and that she wasn’t just this crime victim, and it drove me.

How do you see yourself as a journalist when you’re writing a story such as this? What is your role as a writer?

I’ve been writing since I was a little girl, and that was my way of making sense of the world. Growing up, I didn’t know about women journalists; there just weren’t that many. But my brother was a journalist for a time, and I didn’t have the money to go to journalism school, so I took some classes in copy editing and then I got accepted to the Stanford Publishing Program, which unfortunately no longer exists. My first job was at San Francisco magazine, and I wrote for the L.A. Times for many years.

It’s an intuition about what I really want to write about. I’ve learned something, and I can’t stop thinking about it and know I have to pursue it. It works 90% of the time.

A Northern California tribe has declared a state of emergency over recent violence and is asking state lawmakers for help to solve a crisis of missing and slain members.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

Readers seeking assistance or resources for Native American women can find more information at the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, niwrc.org, and the StrongHearts Native Helpline, strongheartshelpline.org.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.