The truth behind a killing during George Floyd protests — and the lies that made it worse

On the Shelf

The Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American Tragedy

By Joe Sexton

Scribner: 384 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

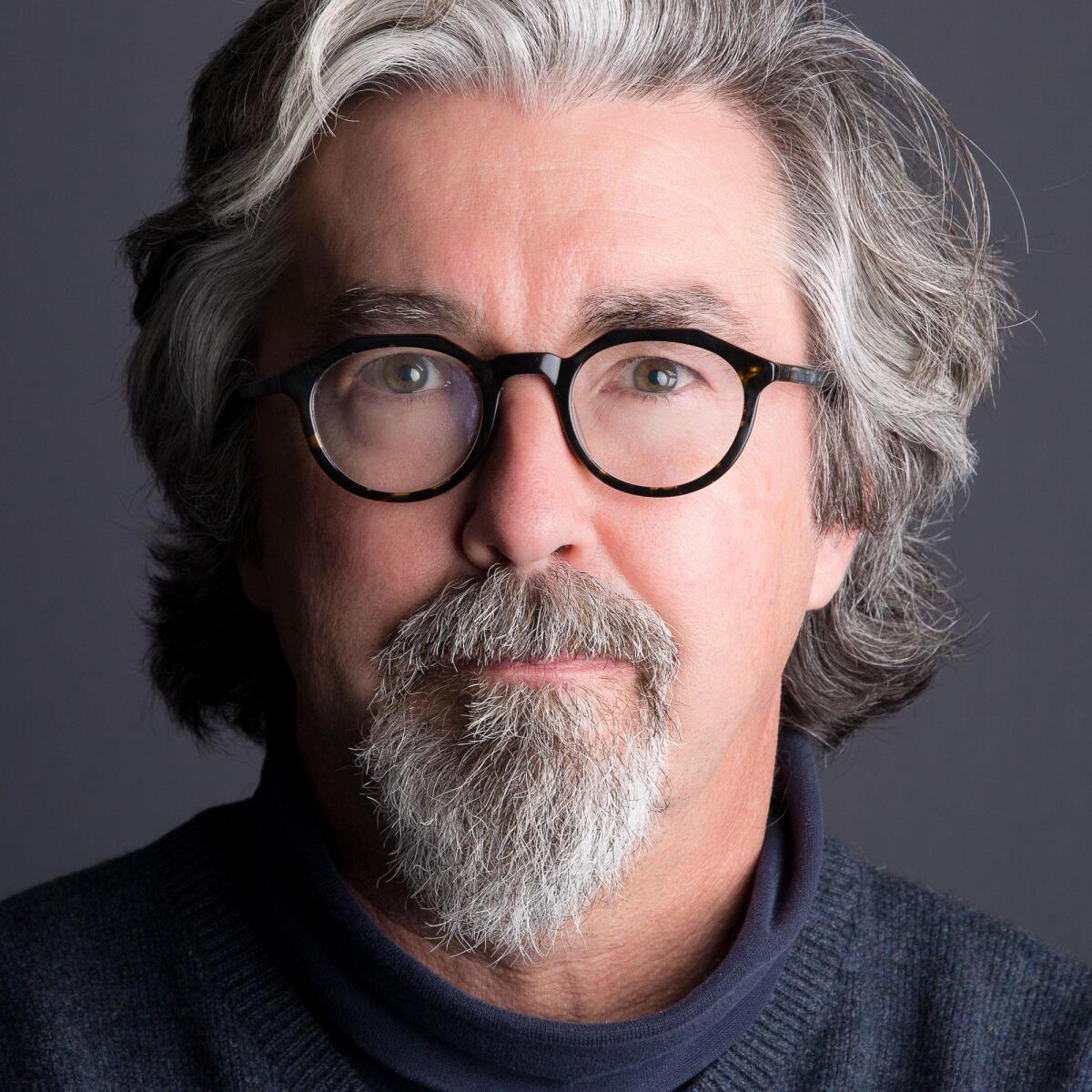

Over decades in journalism, working for the New York Times and ProPublica, Joe Sexton oversaw six projects awarded Pulitzer Prizes; he also shared in three Emmy Awards for documentary films, including one about white supremacists. In other words, he has been widely recognized for seeing America’s problems with sharp-eyed clarity.

Yet even Sexton was thrown off by reporting and writing “The Lost Sons of Omaha,” a book that had him repeatedly using words like haunting, dispiriting and disheartening during a video interview from his home in Vermont.

The book recounts what Sexton calls a “spectacularly unfortunate and humanly understandable” dual tragedy sparked during the 2020 George Floyd protests. Jake Gardner was a former Marine-turned-bar owner. He was also a white man with a gun when he stepped outside his bar, which had been subject to allegations of racism over its dress code, on the third night of protests. James Scurlock was an ex-con, a new father and a Black man who, according to video footage, had been vandalizing buildings, including Gardner’s bar, when he encountered Gardner.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

The moments leading up to their fatal confrontation were captured on video and reported on by eyewitnesses; yet they are rife with ambiguity, allowing everyone to fill in the blanks according to their own agenda.

Scurlock either attacked Gardner unprovoked or acted to defuse a dangerous situation (Gardner had already fired two rounds). Gardner was either looking for trouble or protecting his establishment and his father, who had been shoved to the ground in retreat.

Either way, during their brawl, Gardner pointed the gun behind him and shot Scurlock, killing him. Months later, having fled Nebraska in the face of local outrage, Gardner found himself indicted by a grand jury on a manslaughter charge. Again, Gardner used his gun — this time on himself.

“I was immediately struck by the fact that many of the ills that afflict our country today came to bear in this particular tragedy,” Sexton says. While no single book could adequately unpack them all, he says he hoped to separate the facts from the myths and provide at least some clarity about what truly happened — not just the inciting act but also its ramifications.

“There’s our broken criminal justice system that sends Scurlock behind bars as a teen in part for a crime he committed as a homeless 11-year-old, taking a PlayStation out of a neighbor’s house,” Sexton says, “while Gardner was in the exact cohort of soldiers in Iraq who were hurt before the traumatic brain injury phenomenon emerged,” and therefore his “went mostly untreated by the VA [Department of Veterans Affairs] for 15 years.”

Sexton also explores the red-lining and other causes of segregation and racial strife in Omaha and the U.S. that helped fuel the explosion of anger after Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police.

Those are the ills that led to the deadly showdown between the two sons of Omaha. But the aftermath was quickly poisoned by “misinformation and the menace of the weaponized internet,” Sexton notes. “What was lethal was not that facts were gotten wrong but the instantaneous move to demonize Gardner and subsequently Scurlock.”

Within minutes of the shooting, flawed and false information starts spreading on social media and “an inflammatory and vengeful narrative takes hold. No one is spared.” Throw in the fact that “newsrooms have been eviscerated,” drying up any potential sources of correct information.

Sexton believes these forces have turned us from partisans to sectarians. “You don’t just disagree, you don’t just dislike each other, each side is alien to the other,” he says, “... and a threat.”

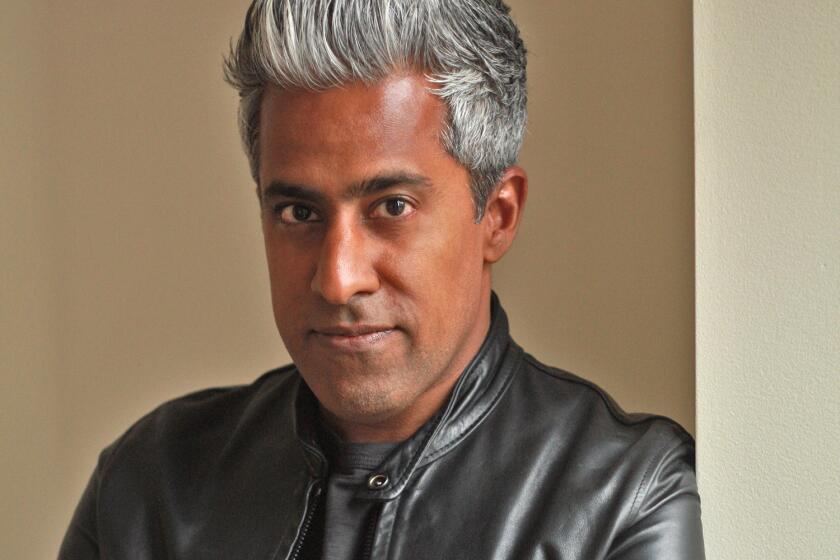

Author Anand Giridharadas advocates for progressive ideas. In ‘The Persuaders,’ he talks to others, including AOC, about how to reach those who disagree.

And when a reporter like Sexton does enter the picture, sectarianism makes his job more difficult. Sources in Scurlock’s camp “would not talk to me unless I stipulated in advance that Gardner was a racist,” he says.

Most upsetting was his experience with a former Marine from Omaha who had enlisted with Gardner before becoming a successful local TV reporter. This particular friend, who would drink with Gardner at his bar each year on the anniversary of the founding of the Marines, was a Black man.

In hours of conversation, Sexton says, the man was “open and honest and conflicted.”

“He told me, ‘As a Black man, I ask myself, “What the hell was Jake doing with a gun out there that night?” As a Marine, if I’d had someone on my back where I didn’t know what they were doing, I probably would have shot Scurlock myself,’” Sexton says. “That was probably the most honest assessment of the whole thing.” Yet the man insisted on anonymity, for fear of losing friends. “The sadness of that will stay with me forever.”

Setting the record straight meant examining some of his own assumptions, Sexton admits. He traced Scurlock’s rap sheet to that PlayStation theft at age 11, which due to prosecutorial indifference not only failed to trigger a social-services intervention but also become a “prior” when he was next arrested, leading to harsher imprisonment and earlier initiation into a life of crime.

“The actual history was a genuine jaw-dropping moment for me,” Sexton says.

Gardner, meanwhile, had been quickly reduced to a MAGA-loving, trouble-seeking gun nut. Sexton found out about the story when an editor told him that “a white supremacist killed a Black kid and got away with it.” But while Gardner and his father were depicted on social and even traditional media as drug-running racists, an investigation proved that false.

“I was fascinated by the idea that false news spreads exponentially faster than the truth,” Sexton says. He also notes that while a Marine, Gardner had been assaulted and curb-stomped in front of a bar, breaking his jaw and knocking out 12 teeth. “It doesn’t absolve him” of using his gun in front of his own bar, Sexton says, but it helps explain his reaction.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

Having established the complicated facts, Sexton goes on to examine the lies that replaced them, pressing those who had spread false accusations on their motives.

Only one, Jennifer Heineman — Gardner’s second cousin, who barely knew him but who used that spurious connection to amplify her attacks — exhibited some remorse and self-awareness. Others, like a local lawyer named Ryan Wilkins who viciously attacked Gardner online, just moved on with their lives without worrying about what they’d wrought. “He might be among the most disturbing people in the whole saga,” Sexton says. “In some moment of self-perceived virtuousness, he blew past every personal and professional guardrail. … That phenomenon is an ongoing threat.”

One point of pride for Sexton is that his reporting named names — Wilkins and others like him. “They based their posts on nothing, so they should be named,” he says.

Reading the book makes it hard to imagine a future with any civility or comity. But Sexton is not utterly bereft of hope.

“The reception to the book will be a measure of my optimism,” he says. While the idea is “mildly grandiose,” he thinks it will be telling if ”a story told straight, which seems like a vanishing phenomenon these days,” can be accepted on all sides.

“Not that my book will solve America’s problems,” he says, “but even if it’s just that the people of Omaha regard it as a fair and necessary telling of a story that has been warped and disfigured and damaging, that’s not nothing.”

He shared the book with members of both the Gardner and Scurlock families, who had been generous in telling their sides of their story. “Both families have respected it and been grateful for it,” he says. “In that, there’s cause for hope.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.