Doctor-novelist Abraham Verghese unpacks his long-awaited new epic

On the Shelf

The Covenant of Water

By Abraham Verghese

Grove: 736 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

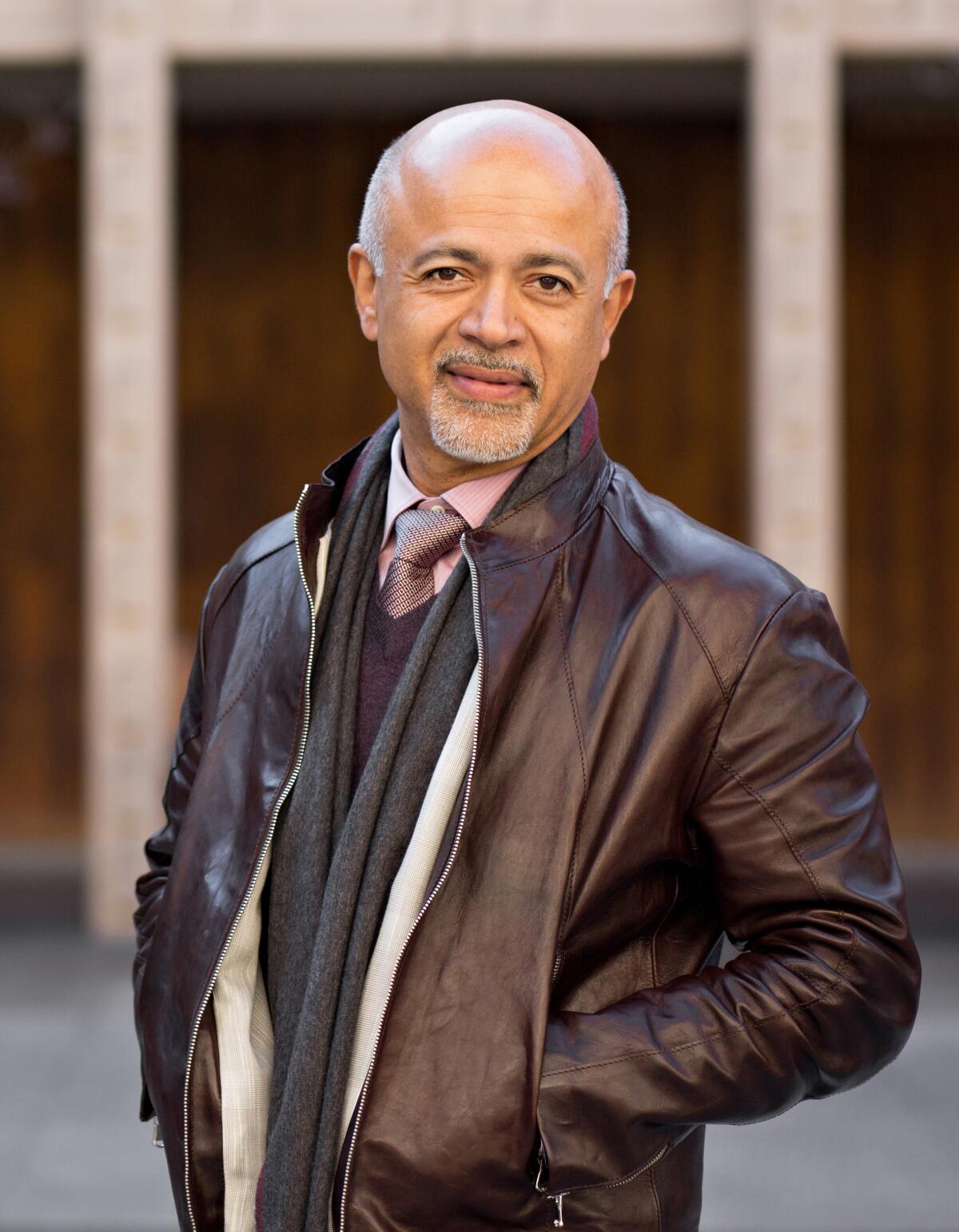

There’s a large whiteboard to the side of Abraham Verghese, acclaimed author and, by day, professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. He swivels in his chair to point to it over Zoom. This is where the cast of his new novel, “The Covenant of Water,” took shape — where he jotted down notes and drew sketches of characters including Big Ammachi, the book’s matriarch, whom we first meet as a 12-year-old bride in South India; her son, Philipose, who chronicles the lives of local villagers in newspaper columns signed “The Ordinary Man”; his wife, Elsie, an artist of transcendent gifts; and their daughter, Mariamma, an aspiring physician.

Yet as the novel grew in scope — it spans seven decades, from 1900 to the 1970s, and more than 700 pages — Verghese found himself constantly reworking things. “It’s not as though I’m without a plan — I have a plan,” he insists. “But what happens is over time the characters pretty much dictate that the plan I had just wasn’t going to work for them. So I’d take a photograph of the whiteboard, erase it, and start again.”

One imagines that Verghese’s long-awaited followup to his 2009 bestseller, “Cutting for Stone,” involved a lot of scribbling and scrubbing: It’s an immense, immersive work, brimming with interconnected story lines that meander and converge like great river tributaries.

Grace Li’s debut novel, “Portrait of a Thief,” blends action with a thoughtful exploration of colonialism and Chinese identity.

It is the story of three generations of one family in the Christian community of Parambil, along the Malabar Coast of South India, a “child’s fantasy world of rivulets and canals” that has “spawned a people — Malayalis — as mobile as the liquid medium around them.” The novel encompasses intense passion and tragedy, as well as a medical mystery: The family suffers from an illness, or curse, which they call the “Condition,” that has caused death by drowning in every generation.

Did Verghese know just how vast an undertaking the book would become? “No, I didn’t,” he says with a shrug. “I think I always had the ambition to write a big book; I enjoy reading big books. There’s nothing else I know that can stop time as effectively as getting lost in a big novel.”

For inspiration, Verghese, 67, drew heavily on his mother’s drawings and stories of growing up in the region. “The Covenant of Water” captures this world as it moves, haltingly, through the 20th century — exploring themes of political upheaval, progress and privilege, death and disease along the way. Her tales, he says, were “so rich that I thought, if I’m looking for a landscape, a geography — and I always felt that geography is like a character in any book — then here was one that I knew well.”

He has known many landscapes. His parents, members of the St. Thomas Christian community of Kerala, were hired by Emperor Haile Selassie to teach in Ethiopia, where Verghese was raised. Most summers, he would return to his grandparents’ village in India. His memories, he says, “are still tinged with the lamplight of that era” before electricity.

He began his medical training in Ethiopia, but civil war intervened and Verghese came to the U.S. to work as a nurse’s assistant. He eventually finished his coursework in Madras (where Mariamma studies in the novel). Both experiences, he says, instilled in him an appreciation of “the bedside and the body as opposed to the technological emphasis we’ve slipped into now.”

Deepti Kapoor’s “Age of Vice” comes bearing “Godfather” comparisons and an FX series deal. But in favoring glitz, the novel loses sight of India’s poor.

Verghese sees a symbiotic relationship between his twin professions, and he brings a similar sensitivity to each. “I’m an internist and by nature we tend to be very attentive to what the body is saying,” he explains. “I feel like I try to bring those qualities to writing. … I resist the notion that it’s two different things. In my mind, I see myself as just this one being, all physician, and I think the lens I bring to the world, whether in the hospital or writing something, is the same lens.”

Though he is an infectious disease specialist by training, Verghese says he spent the COVID pandemic for the most part removed from the front lines of emergency rooms. Yet he watched in horror as other parts of the country were under siege, including his former home of El Paso (the setting of his 1998 memoir, “The Tennis Partner”).

The period also brought back painful memories of the 1980s AIDS crisis, the subject of Verghese’s first book, “My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story.”

“It was a very intense experience,” he says of the last few years. “Firstly, in the sense that I felt I had already lived through the defining illness of my career — and then something came along that completely eclipsed it. So it was really kind of stunning, with many, many echoes of the AIDS epidemic for me personally.”

Working on “The Covenant of Water” as COVID raged also opened up stark and poignant parallels. “Here I was writing about illness and death in the 1900s, and it just felt to me that nothing had changed in terms of the things we turn to for sustenance in times of great challenge,” he says. “What matters are things like family and loved ones, people who are willing to make sense of your life for you even as it’s slipping away.”

Verghese believes the literature of the pandemic has yet to be written — but it will. “Very much like HIV, I think one has to wait a little bit to digest what happened,” he says. “I’m sure we’ve already seen many, many narratives, but I think we’ll see more quality ones as time goes on.”

Perhaps Verghese will help write that story himself, returning to the mix of reportage and memoir of his earlier books. But for now, he has embraced the broader, freer canvas of make-believe.

Your ultimate L.A. Bookhelf is here — a guide to the 110 essential L.A. books, plus essays, supporting quotes and a ranked list of the best of the best.

“The great liberation of fiction is that you can do anything you want, but I think you have to work 20 times harder to get the reader’s attention and keep it,” he says. “It’s a different kind of enterprise altogether, but I enjoy it much more than I think I do nonfiction.”

There’s a saying in the novel that Philipose repeats like a mantra: “Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth about how the world lives.” It’s a sentiment that resonates with Verghese, who feels an affinity for Philipose’s workmanlike approach. “I identify with Philipose in a way,” Verghese admits. “There is true genius in the world and there are people, I suppose like me, who just slog at it and in the end you have a product.”

“The Covenant of Water,” of course, is much more than that: It’s an essential, even healing feat of imagination, a whole world to get lost in. May Verghese continue to slog away, wiping clean his whiteboard over and over again.

Tepper has written for the New York Times, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places, and is curator of international literature at City of Asylum in Pittsburgh.

Verghese will discuss “The Covenant of Water” with Aimee Liu at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica for a Live Talks Los Angeles event at 8 p.m. May 3.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.