One L.A. writer’s heartbreaking tour of the school-to-prison pipeline

On the Shelf

'Children of the State: Stories of Survival and Hope in the Juvenile Justice System'

By Jeff Hobbs

Scribner: 384 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Children of the State,” Jeff Hobbs’ new book about children caught up in the juvenile justice system, includes some history. There are some telling statistics and discussions of public policy. But ultimately, all of those are bit players: For Hobbs, whose “The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace” won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize, storytelling is about the people. So above all, this sensitively written book offers finely wrought portraits of the teenagers in juvenile hall, as well as the educators and counselors trying to help them find safe passage back to — and through — the real world.

“When I’m doing the work, I focus on the small scale, on the individuals and the relationships,” Hobbs said by video from his home in Los Angeles. That was the approach he took with his book about Robert Peace, a bright young man from Newark, N.J., who managed to escape the streets and attend Yale but remained an outsider and was murdered at 30.

With “Children of the State,” Hobbs does zoom out to note that a quarter of a million kids serve in some form of detention each year: “The impact on their lives is deep and long term.” He knows some of these kids need to be locked up at least briefly — “if you pull a gun on someone there needs to be consequences” — but he believes passionately that their lives still have value, and he hopes to inspire readers to volunteer or advocate for or at least care about the children inside those closed-off buildings.

Hobbs’ narrative gets us inside the heads of his subjects in the depths of the night, when he clearly wasn’t there. “I always ask people about their emotions,” he explained. “I sometimes feel like I’m overstepping, but if you want to get readers to care about them you have to go there and get those details.”

“Children of the State” is divided into three sections, with Hobbs immersing himself in different programs around the country for seven months. In the first, at the only youth residential detention facility in Delaware, Hobbs focuses on the story of Josiah Wright, serving a one-year sentence for a violent crime.

Kristin Henning has represented young Black defendents for decades. In ‘The Rage of Innocence,’ she makes a powerful case against police in schools

The middle section, set in the Woodside Learning Center in San Francisco, emphasizes the educators, especially the principal, Chris Lanier, and one English language arts teacher, Megan Mercurio. Hobbs explores the ways the program strives to educate these children but also the toll it takes on the adults. “I was really surprised by the level of caring and investment in the classrooms, which causes a lot of burnout,” he said. “You really are close to tragedy in there.”

The final section focuses on the program Exalt Youth in New York, which keeps kids out of detention; they go to their own high school, then come to Exalt to learn life lessons and get paid internships that will help prepare them for the life available to them if they can stay out of trouble. Here, we are introduced to Ian Alvaro and the program’s teacher, Alex Griffith, who struggles to keep Ian moving forward.

Hobbs’ in-person research was interrupted by the pandemic; he continued following the stories but felt that the lockdown deprived him of the chance to focus as much as he’d planned to on the guards and counselors in all three facilities.

There is no sense of such limitations for the reader; we feel we are always in the room. There are scenes of heartbreak (a recent alum of one program is murdered soon after returning to the streets) and more everyday frustrations (given 30 minutes to write an essay, some students jot down a sentence or two while most leave their pages blank). But there are also just enough bright signs to justify the book’s subtitle, “Stories of Survival and Hope in the Juvenile Justice System.”

“Hope is a tricky word,” Hobbs acknowledged. “I certainly see it in these stories. Still, if you look at juvenile hall, it’s about the erasure of potential. I wanted to show how hard it is to come out the other side.”

In ‘Master Slave Husband Wife,’ Ilyon Woo follows a wife and husband who escaped by posing as a white man and his caretaker, then fought for abolition.

For those teens who can respond, a good program with caring educators and counselors can be a “reset point,” Hobbs said. One teacher notes that for kids who attain their degrees in juvenile hall, or at least credits to finish high school afterward, even just doing OK by many societal standards amounts to a “spectacular” outcome.

Hobbs notes that nearly all the children who end up in juvenile hall are poor and from communities of color — and many of them are also weighed down by loss, violence and other traumas. As a result, Hobbs writes, they live in the present and are haunted by their pasts but can rarely envision their future.

“Some of these traits — not being able to look down the road, being told what to do by adults who don’t take your ideas seriously — are fairly universal for teenagers,” he says. But for students with trauma and not much support at home, it risks becoming a permanent condition. “There’s often a deep hopelessness about, ‘What’s out there for me after this?’ Kids in class are constantly muttering about that, so they might as well fight somebody or give the teacher a hard time.”

While Hobbs is reluctant to presume enough expertise to make prescriptions, he says these schools are badly understaffed and need more counselors. “It really did feel like the moments of progress happened when it was just a kid and a caring adult sitting across from them, looking them in the eye and listening,” he said.

He believes state-funded programs that could guarantee vocational training and jobs for graduating students would help those kids envision that elusive future. That kind of support “is the major dream of many of the people I worked with for this book,” he said.

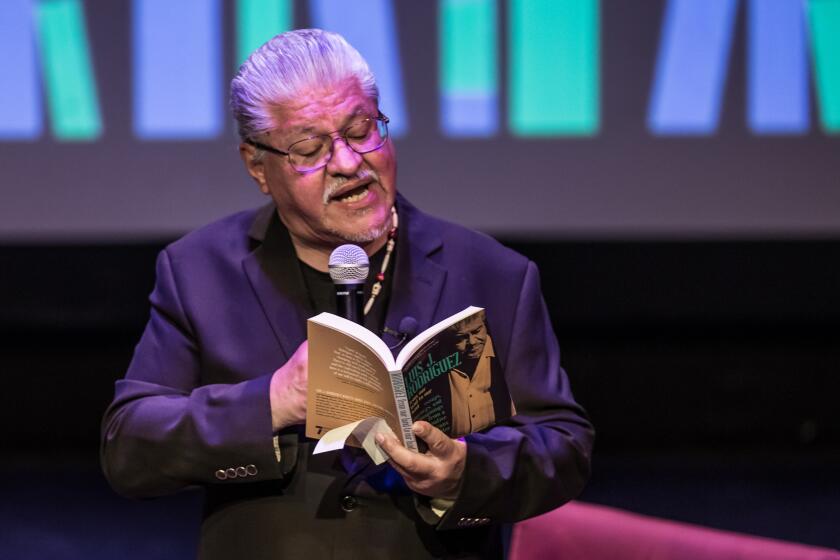

Luis J. Rodriguez shared his new book, ‘From Our Land to Our Land,’ with the Los Angeles Times Book Club

One reason he’s reluctant to prescribe is that he knows he’s an outsider, a privileged “white guy” whose children went to a preschool where even parents discussing timeouts prompted gasps. (“You’d get the stink eye for weeks,” he said.)

“I definitely cannot for a second say I am understanding anyone’s perspective here,” despite all the time he spent talking to his subjects, he said. He knows some readers may even insist these aren’t his stories to tell.

“I don’t have a clean answer to that because there isn’t one and I struggle with the question,” he said. He faced the same issue while writing the book about Robert Peace.

“One day I was driving around with a close friend of Rob’s nattering about this exact question,” Hobbs recalled. “We were at a stoplight and he said, ‘Jeff, I’m not going to give you permission, and I certainly can’t give you absolution. But if you’re listening, maybe I can help you understand. And then because you’re a white guy, maybe you can help other people understand.’ He was just trying to get me to shut up. But it’s what I hold onto as I do this work.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.