Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

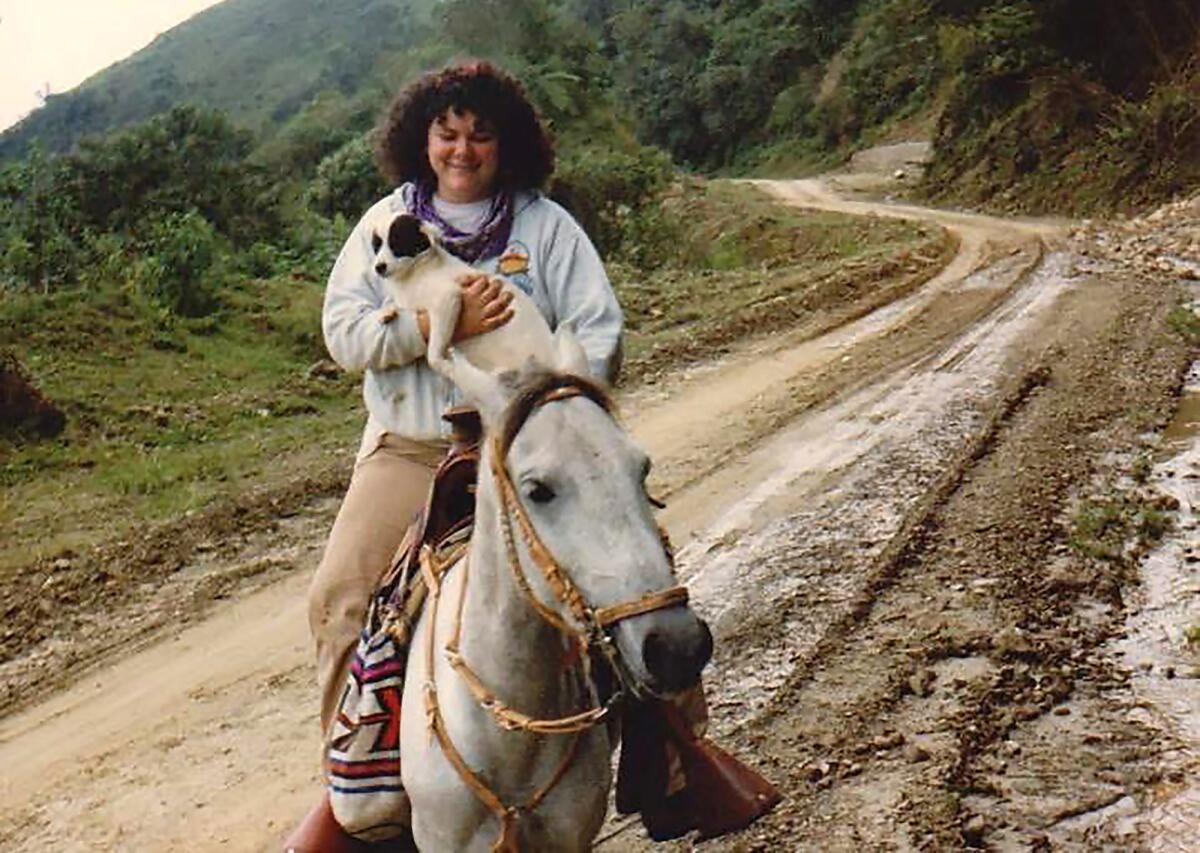

The majority of American readers are, unfortunately, unfamiliar with the name tatiana de la tierra. By way of introduction, here is how the late writer described herself in the essay “Aliens and Others”: “I am a fat, slightly bearded lesbian. A white Latina of Colombian extraction. A pagan lacking in Catholic guilt. A hedonist who knows shame. I have been diagnosed with lupus. Drive a pink and purple pickup. Collect rocks. Been poor most of my life. Knew gold-plated Gucci wealth for a few memorable years. I am a writer.”

De la tierra was born under a different name in Villavicencio, Colombia, in 1961, grew up in Miami and died in Long Beach, Calif., in 2012. She wrote fierce, bawdy, politically outspoken literature and edited some of the first Latina lesbian publications distributed in the U.S. and Latin America. Though she herself never broke into the literary mainstream anywhere, she wrote of and for writers at the margins of the margins everywhere.

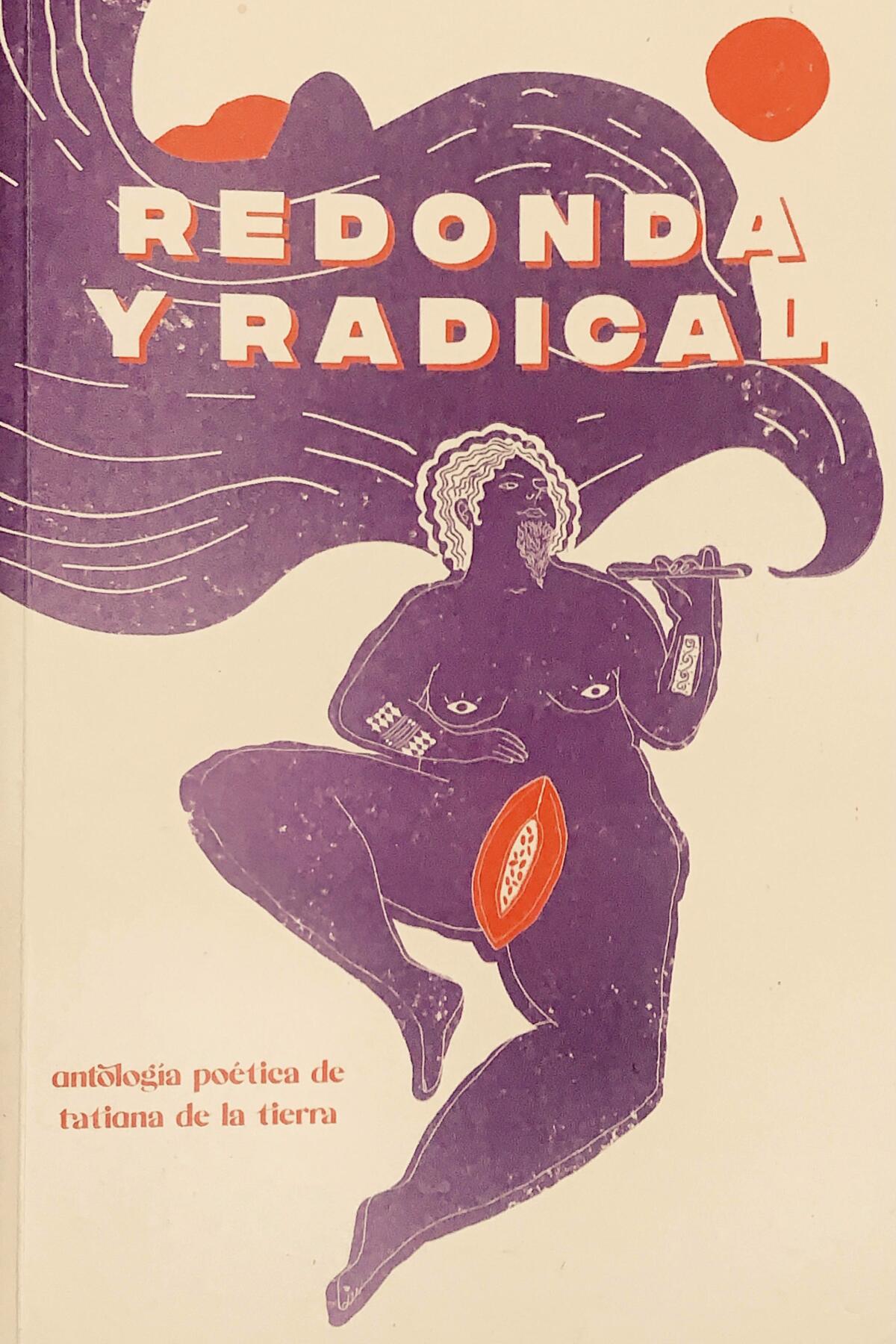

This fall, a Colombian publisher has compiled her chapbooks and a few other works into a single collection for the first time under the title “Redonda y Radical.” With any luck, this is just the beginning of a long posthumous career.

During her lifetime, de la tierra published two professionally bound books. The first was “For the Hard Ones: A Lesbian Phenomenology,” described as “A lesbian manifesto for hardcore dykes, baby dykes, and wanna-be lesbians.” A bilingual edition was brought back into print in 2018. Her other book, “Xia y las mil sirenas,” published in Mexico in 2009, was a children’s book about mermaids, lesbian mothers and the power of chosen family.

The vast majority of her work, however, was self-published during the 2000s in chapbooks under the moniker of Chibcha Press and distributed by hand at music festivals, lesbian gatherings and literary events. Some of these chapbooks found inspiration in publishing traditions throughout Latin America — such as the methods of the cooperative Eloísa Cartonera in Argentina, which began making handmade books with cardboard covers (cartoneras) after the economic crisis in 2001. A champion of self-publishing, de la tierra would recycle paper and scavenge cardboard, then decorate her cartoneras by hand, creating works that were truly one-of-a-kind.

The writing itself was just as singular — unassimilated and unafraid even by today’s standards. Her poem “Big Fat P— Girl” is an unabashed litany of praise of her genitalia, beginning with “Queen-size c—” and piling on further epithets: a “whaler of a c—,” a cruise ship, the World Wide Web, a Cadillac, a castle, an eagle, Jupiter, the Library of Congress, Disney World and, finally, “the Sonora Matancera of C—.” Her work isn’t always so explicit, but it’s persistently sexy and hilarious.

Bay Area novelist Ingrid Rojas Contreras tells of how a head injury led her to revisit the shamans in her life — and her native Colombia.

It is also unique in its treatment of bilinguality. Some authors use Spanish words only when there is no direct English equivalent. Others may choose to fluctuate between English and Spanish in a way that ensures it remains accessible to non-Spanish speakers. De la tierra would produce some works only in Spanish, others only in English and still others in Spanglish. She wrote without concession to the borders of any language or nation.

Her writing was also as sonically rich as writing can be. She sometimes brought instruments to readings. On the musicality of her work, her mother, Fabiola Restrepo, said, “I would read poetry to her, even when she was potty training. Well, more than read, I would recite to her. Rafael Pombo is one of the poets I would recite to her.” Luckily, there are still recordings of de la tierra voicing her incantatory work.

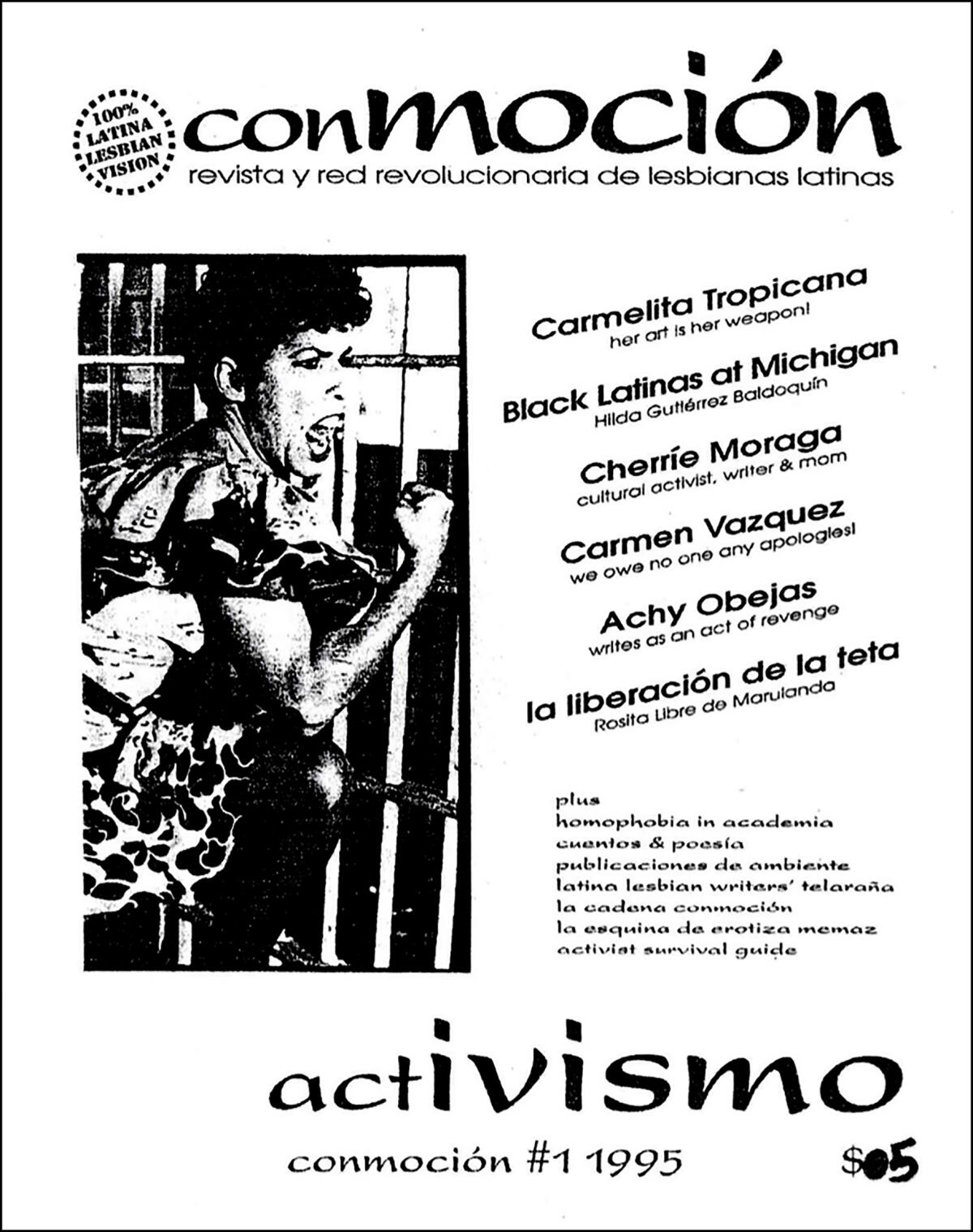

A talented performer of her writing, de la tierra was also a prolific amplifier of other voices. She helped to found esto no tiene nombre (this has no name), a transnational literary publication dedicated to Latina lesbians. The journal, which published nine issues from 1991 to 1994, was founded as a newsletter by a Miami collective of queer Latinas who called themselves Las Salamandras de Ambiente.

From the start, however, the collective was factionalized by editorial choices that some deemed too radical. One of the biggest rifts was over an essay from de la tierra on the lesbian pornographic videos “Bathroom Sluts” and “Dress Up for Daddy.” In an essay, “Activist Latina Lesbian Publishing,” she detailed the clash within the collective.

“We believed that publishing had the power to transgress invisibility … that expressing lesbian sexuality was good and fun and healthy, and that what we were doing was meaningful,” she wrote. “We saw internalized homophobia as the real crux of the matter. Several of Las Salamandras were offended by the word ‘lesbian’ on the cover. Many were not ‘out’ publicly and did not intend to be.”

After Las Salamandras withdrew their support, de la tierra helped transform esto no tiene nombre to court audiences far beyond Miami. She even appeared with her mother on a Telemundo segment called “Cuando su hijo es gay” (“When your child is gay”) — on the condition that the program include a plug for the journal.

Though esto no tiene nombre began attracting more grants and institutional support, it ultimately folded for a number of reasons. “Hurricane Andrew devastated us,” said former co-editor Patricia Pereira-Pujol. “Our relationships faltered and eventually cracked. We were young and learning the business of publication as we went. We worked full time, and growing the publication as we envisioned became unsustainable. I wish the opportunity had come to us at a time when we were better prepared.”

Meet the inaugural LA Vanguardia class, talented Latinos defining the cultural landscape of L.A. and beyond.

De la tierra, however, wasn’t quite finished with publishing. She worked to evolve esto no tiene nombre into Conmoción, a successor with a larger budget, wider distribution and a national editorial advisory board. After three issues, Conmoción also folded and de la tierra began to focus more on her own writing, having given her time so generously to others.

These publications were not the first venues for conversations about queerness and Latinidad. Several pioneering anthologies (such as “This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color”) had laid the groundwork in the 1980s. Nonetheless, de la tierra played a critical role in feminist literary history as a bridge between those early intersectional forays and our modern era (when representation is greater — but often at the cost of assimilation). Always pushing boundaries, she challenged what was considered acceptable discourse.

When thinking about her peers in the literary world, it’s hard to say why de la tierra didn’t find wider acclaim. She was writing after Audre Lorde and other lesbian activist writers first broke through — and just as Latina authors including Sandra Cisneros, Helena María Viramontes and Ana Castillo were garnering mainstream attention. Yet she never gained the traction that they did.

Was she too far removed from New York and the power centers of the publishing industry? Too queer and crass to be shelved alongside Cisneros? De la tierra was always just a little bit outside of legibility.

So where does she belong? Maybe it’s as simple as this: everywhere and nowhere. She reinvented herself constantly — which makes it difficult to define her legacy.

In 2007, years after completing a master’s degree in library science at the University of Buffalo, de la tierra moved to Long Beach (a psychic had advised her that the vibration of the land there aligned with her spiritually) and started to work at Inglewood Public Library. She was a member of the organization Reforma, which promotes library and information services to Latinos and Spanish-speaking communities.

In California, de la tierra found a home among Latina writers who cherished her talent. She joined several writing groups, including Las Guayabas, a Latina writing collective whose members included well known authors such as Estella Gonzalez, Myriam Gurba and Carribean Fragoza.

Carribean Fragoza’s “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You” is a debut story collection ripe with surrealism but grounded in the soil of Latina experience.

Gurba, the author of “Mean,” remembers de la tierra as a proud scofflaw, in the best sense. “Paper can be expensive, ink can be expensive, staples can be expensive,” Gurba said. “So if those were somehow in arms’ reach of her environment, she would take them. That’s what she would do and she would encourage me to do the same. … It was theft in service of art.”

Griselda Suarez, executive director for the Arts Council of Long Beach and another member of Las Guayabas, shared a similar memory, revolving around a trip they took together to Denver for AWP, the large annual conference of writers and writing programs. “She actually went as my wife; we got a discount that way.” Suarez was happy to participate in de la tierra’s literary hustle.

In the final months before her death from colon cancer in 2012, de la tierra renamed herself Suerte Sirena, as if preparing to transition into the next phase of her life. After her death, Olga García Echeverría, one of de la tierra’s literary executors and a professor at California State University, Los Angeles, wrote that the author, “who believed in the power of metaphors, created an alternative reality for herself. The cancer cells blooming wildly inside her were not evidence of imminent death; they were proof of a metamorphosis. tatiana would not ‘pass away’ into heaven or hell. Instead, she would shed flesh and blood and swim back to her divine beginnings, the Cosmic Ocean.”

At the time of her death, de la tierra was working on a collection of stories about her family. She also left behind an unpublished novel about Colombia, which was her master’s thesis for the University of Texas at El Paso, and an English translation of poetry by Cristina Peri Rossi, the renowned Uruguayan author. Her archive is held at UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center and will be digitized in coming years. Most of her prolific output remains unpublished or self-published.

Noriega, stepping down as director of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, talks about the importance of Chicano history and whether Ben Affleck should play him in the movies.

It’s time for American publishers to give tatiana de la tierra her due. She should be read and remembered for exactly the thing that might have contributed to her obscurity: She would not compromise. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see how many of the ideas she lived by — intersectionality, body positivity, sexual candor — have become almost mainstream. Now that the world is catching up, we should celebrate this writer by unearthing her work, so she can be properly honored by the literary world as she never was while she lived.

Soto’s debut poetry collection, “Diaries of a Terrorist,” was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2022.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.