Review: Wrapped inside a dystopian novel, an epic of ‘radical compassion’

On the Shelf

Meet Us by the Roaring Sea

By Akil Kumarasamy

FSG: 304 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In “Meet Us by the Roaring Sea,” the first novel by Akil Kumarasamy, an unnamed young woman grieves the sudden death of her mother. She lives in her mother’s home, surrounded by her mother’s archive, mundane belongings alongside treasures of questionable authenticity, and tries to leave it all untouched, a record of her mother’s existence. Perhaps as a counterbalance to this stagnation-cum-preservation, she becomes obsessed with translating a manuscript, even though she suspects its authors “wouldn’t want to immigrate to English.”

Kumarasamy moves between the unnamed narrator’s present-day, which is our future (carbon scores are a thing, AI has improved significantly), and sections of the manuscript she’s translating. She describes this document, written in the late 1990s, as “a collective memoir, not fully fact or fiction, about a group of female medical students, all of them under the age of twenty-one, not quite doctors or mystics.” Written in Tamil, an ancient language very much in use, the manuscript links the protagonist with the past, to a time when her mother was alive.

The narrator’s life is quiet, at first. She works at ML Consulting, where she’s a well-paid coder training AI programs. She comes home and watches TV with her cousin Rosalyn, who is obsessed with a reality show called “Soldiers’ Diaries” that follows American troops deployed to unspecified “stabilization zones.” After the parents of a childhood neighbor, Sal, are killed in an autonomous vehicle incident (a driving algorithm sacrificed the Ahmeds for a white woman and her toddler), Sal moves into her childhood home, reuniting her with the protagonist after many years apart.

The interpolated sections of the translated manuscript portray a group of teenage girls living and studying in what seems to be the coast of Tamil Nadu, a South Indian state. “How many first-year [medical] students were able to operate on patients?” the girls write, obliquely referring to the Sri Lankan civil war and the refugees fleeing the island nation for India’s shores. “Our parents prayed at the temple, the mosque, the church, thanking the Lord for the misfortune of others,” they continue wryly. “As long as people suffered, we would be employed.”

“Klara and the Sun,” Ishiguro’s first new novel since winning the Nobel Prize, harks back to his masterpiece, “Never Let Me Go,” and is nearly as great.

That suffering is essential to the girls’ lives beyond their training, as they are devoted to becoming “not only doctors but saviors.” They follow three senior students, Avvaiyar, Baseema and Leela, in the path of what they call radical compassion.

Pain and compassion circulate through both narratives. In the protagonist’s chapters, Rosalyn finds a houseless veteran nicknamed Cheeze who appeared on “Soldiers’ Diaries” and brings him home. By letting him stay, the protagonist aims to practice her own radical compassion, though it proves challenging. The girls in the manuscript, meanwhile, go hungry due to drought and food shortages, even as they’re treating worse-off refugees, but also begin deliberately practicing their mentors’ divergent approaches to radical compassion, from self-denial to bodily pleasure.

“Meet Us by the Roaring Sea” is under 300 pages, and there is certainly a lot going on, but it all feels beautifully balanced — chapters threaded together nimbly, the translated manuscript and the protagonist’s life echoing each other. Human and technological horrors fill the background of both narratives: in one, civil war, government corruption, disappearing fishermen and television broadcasts both blaring and burying the news; in the other, military proliferation, a complete erosion of privacy, eugenicist AI and climate change.

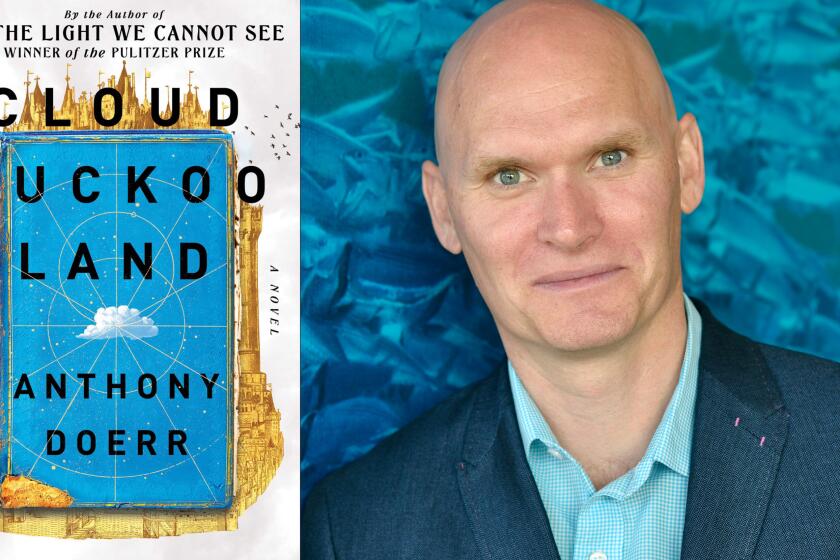

Plenty of novels have worked in the mode of book-within-a-book — the annotated manuscript in Jordy Rosenberg’s “Confessions of the Fox”; the pastiche of academic texts in A. S. Byatt’s “Possession”; the translated Greek manuscript in Anthony Doerr’s “Cloud Cuckoo Land”; the novel-within-a-novel of Susan Choi’s “Trust Exercise.”

The beauty of this mechanism is that it has been and can be used in such different ways, for such different purposes. In “Meet Us by the Roaring Sea,” the translation-within-a-novel demonstrates how, across vastly different times, places and cultures, human beings ultimately have similar concerns: their health and their families — whether chosen, inherited or foisted together — and also the need to be nourished beyond the essentials, to feed what some might call the soul and help alleviate, endure or embrace the suffering endemic to human experience.

An Israel-born critic was wary of Rebecca Sacks’ kaleidoscopic debut, ‘City of a Thousand Gates.’ Why she wound up loving it.

Personally, I love when novels play with form and storytelling modes, but some find these devices gimmicky or too obvious. “Meet Us by the Roaring Sea” avoids this in part because the connection between the sections is never spelled out beyond the fact that the unnamed narrator is translating a manuscript; Kumarasamy is also such an assured writer that you trust her completely, sentence by sentence.

Both the novel’s threads also eschew common narrative voices, opting instead for second person in the narrator’s present-day sections and the plural first person in the Tamil manuscript. As a result, each has a slightly detached, dreamy quality that implies a displacement of the self. For the girls, this echoes their deliberate practice of learning “how to empty ourselves in order to let someone else in and feel their pain so deeply until it was our own.” The narrator must similarly empty herself to let in these voices from another era, to feel their pain and joy deeply enough to create a translation that honors and represents them truly.

Toward the end of the novel the protagonist acknowledges that she is “apart from this world and vulnerable to it.” It’s a deceptively simple statement that neatly summarizes the overarching theme: that existential loneliness exists alongside the deeply porous experience of being a human in a social world. It’s the tension of that seeming contradiction, as well as the sure hand of the book’s guiding intelligence, that makes “Meet Us by the Roaring Sea” such a pleasure to read.

Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

‘Cloud Cuckoo Land,’ Doerr’s followup to ‘All the Light We Cannot See,’ ambitiously maps a world connected by stories — if we know how to read them.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.