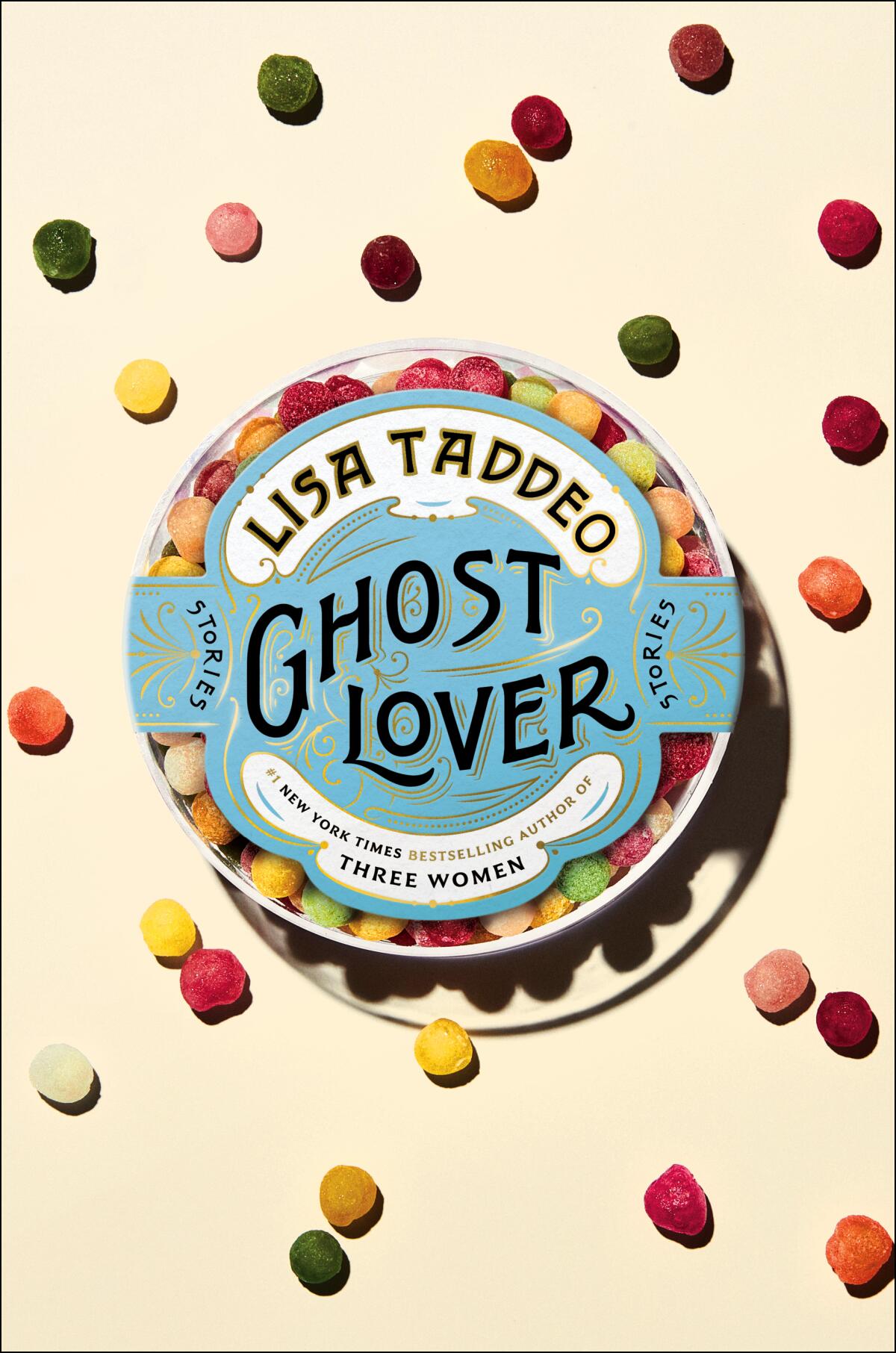

Review: Author Lisa Taddeo’s parade of women who want to be wanted

On the Shelf

'Ghost Lover: Stories'

By Lisa Taddeo

Avid Reader: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Lisa Taddeo has a type. Both her bestselling nonfiction project “Three Women” and her 2021 novel “Animal” explored the dangers and the thrills, the violence and the ache of a specific shade of sexual desire. Her new story collection, “Ghost Lover,” is populated similarly by women who want most of all to be wanted, mostly by men, though what they want even more is for the women around them to be jealous of how much they’re wanted by men.

In the story “American Girl,” three women triangulate around a mediocre politician, all of them desperate for him, none having much of a sense of themselves beyond their one pursuit. In “Forty-Two,” a self-proclaimed “cougar” of that age (though she hates the term) gets ready to attend a wedding of a man she’s tried to steal; in “Beautiful People,” a production assistant sleeps with a gorgeous movie star who cooks her osso buco and ultimately swindles her; in “Maid Marian,” a woman tries to make sense of her hatred for her older lover’s wife after his death. In “Grace Magorian,” Grace — “still single because she wasn’t enough of any one thing” — lies about her age and contemplates posting photos of other women on a dating app in hopes of finally finding love at 51.

These women think a lot about the food they eat, the clothes and shoes they wear. They do yoga and Pilates, take Ambien, Ativan and Klonopin, throw up and starve themselves. They deem 37 to be the age at which most of us disappear. Often they talk, wantonly and unconvincingly, of killing themselves or the men they love. Almost always, they have something tragic and violent in their past. Their interactions with one another are ruled most of all by their compulsion to assess and compare.

Lisa Taddeo, whose book “Three Women” broke the mold of immersive journalism, talks about her first novel, “Animal,” and the struggle to write and live.

To call these women unlikable feels laughable: When and how will we ever move past that term? These women do not care. If you’re thin enough and hot enough, if you lie enough about the right things — your age, your orgasms, your wants and needs — nobody has to like you to keep you around, to give you gifts so large you can sell them and make more than a teacher or a restaurant worker might earn in a year.

These women sometimes have jobs and interests beyond men, but they are almost never relevant to the action of the stories in this book. When a job does feature, as in the title story, “Ghost Lover,” it’s propelled by the main character’s relationship to men. Devastated by a breakup and encouraged by an old friend she also sleeps with (“He felt like a soft iron inside you, something plain and graceless. The dumb pain of simple rod sex. You did not come”), Ari starts a business: a forwarding system for text messages. Women hire Ari and her army of stunning women — “You always brought on women you would imagine him wanting” — to respond, or not, to text messages sent by their crush. The business becomes wildly successful, but Ari is still miserable because the man she still wants still doesn’t want her back.

This is a consistent thread of the collection: wanting and not being wanted, not being wanted and feeling fury — fury at the world and other women, sometimes at men, but most of all at oneself. In “American Girl,” the rare story in which our main character gets the man she wants, it’s provisional, tainted and a little sad: “There were no problems. He said, I love you with every piece of me. Nothing he said was ever specific or realistic. She wanted him more than he wanted her. But there were no other problems.”

The two stories built around female friendship, “A Suburban Weekend” and “Air Supply,” seem at first to be more of the same — fixated on who gets looked at first, whose particular style is more appealing on any single day, at a Mexican bar or a country club pool. Yet these stories slowly grow into other, deeper concerns: a young girl’s grief, a new mom’s confidence in the face of impossible precarity and fear.

Time passes and the stakes of these women’s wants and misdeeds become higher, but you get the feeling that the characters will largely stay the same. “We would turn twenty-four and twenty-six and thirty. We would be leaving an acquaintance’s funeral — heroin, Cape Cod — and the dead boy’s father would turn to look at us, our rears. We’ve still got it, Sara would say. I laughed out loud, because I’d been thinking the very same thing.”

Novelist Lynn Steger Strong on the revolutionary passivity of Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh and Sally Rooney — how we’ve misread them and what comes next.

All of this feels exactly as Taddeo intends it. Books and stories are often premised on the idea that we’re there to watch people in a process of transformation, but often people don’t change at all. Often people (and societies and systems) stay the same. Taddeo conveys the tragedy of this stagnation: messy, increasingly destructive, often very sad. These are women so entrenched in societal expectations, the ghosts of their own tragedies and self-hatred, which they will likely never quite escape.

This sameness and this sense of stuckness has a straightforward and somehow pleasing flatness, as if Taddeo’s goal is to give us not a fully fleshed-out person but instead a single sharp and lacerating slice. You might not know anyone like these women, but chances are that every woman you know holds at least a little bit of these women inside of them.

“Ghost Lover” feels built to provoke — and it’s provocative. It pricks and prods you with its unrelenting focus on the many ways inhabiting a certain type of female body can ruin a life. Yet, as the stagnation spreads, the edges dull. While “Animal” had the time and space to drive its devastating narrative home, here each new story seems to undermine its predecessors.

That is not to diminish their moments of power; the sentences accrue a confidence and clarity by virtue of never having to cast around for what else these characters or their stories might contain. Yet they are too much of one type to puncture quite as deeply as they might have if they’d been allowed to delve a little deeper into what it is to be alive.

In Lynn Steger Strong’s ‘Want,’ a writer, teacher and mother faces up to her own privilege and the precariousness of her middle-class life.

Strong is a critic and novelist. Her forthcoming novel is “Flight.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.