Review: A riveting biographer — and mother — works to solve ‘the mind-baby problem’

On the Shelf

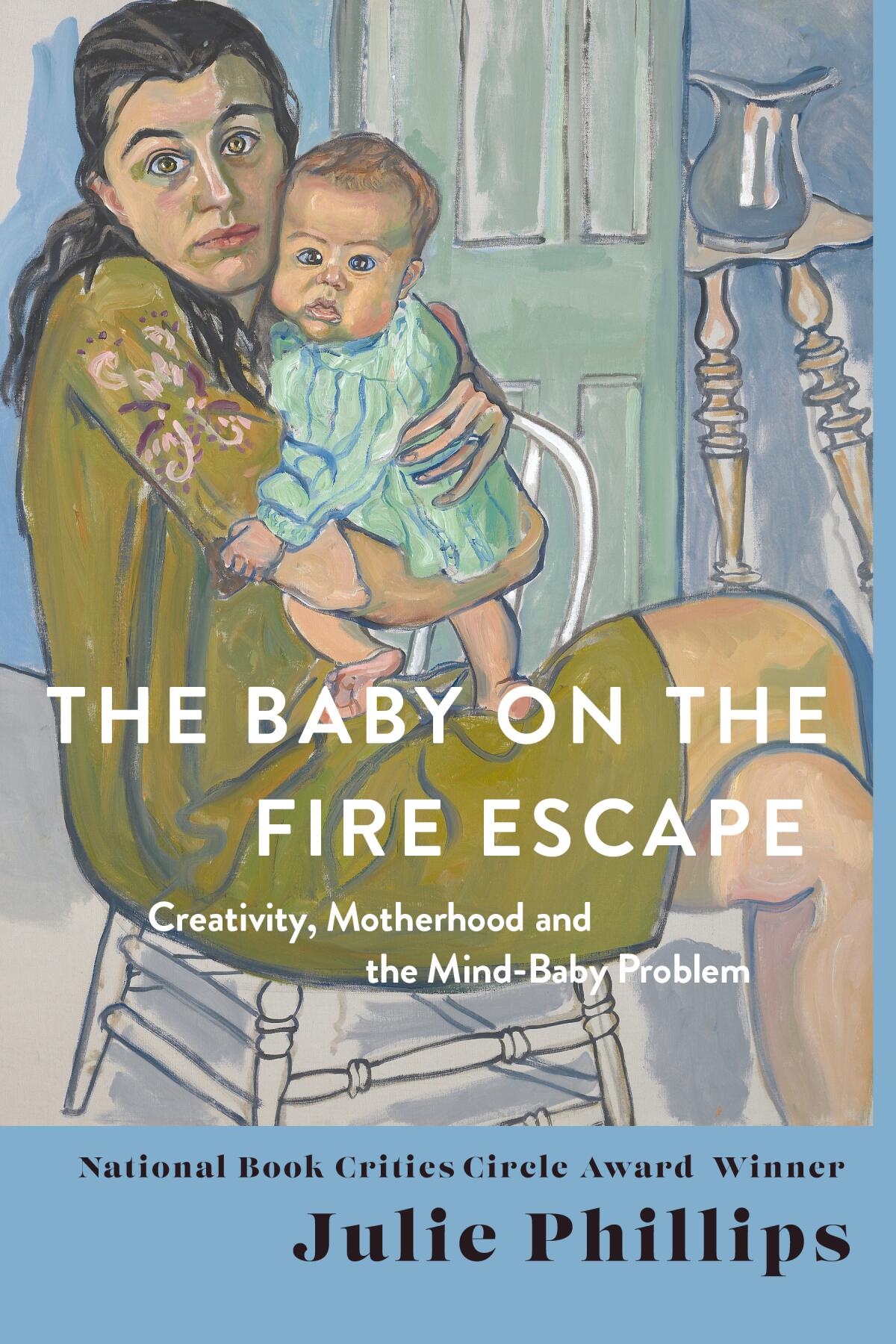

'The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem'

By Julie Phillips

Norton: 320 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Juggling motherhood and creative work can leave one feeling like an iconoclast and a failure all at once. “The Baby on the Fire Escape,” Julie Phillips’ tremendous group biography and exploration of what she identifies as a “mind-baby problem,” focuses on women of the mid-20th century onward, when “motherhood went from being an accident and obligation to being a choice.”

Phillips moves deftly through key moments in the lives of her subjects — Alice Neel, Doris Lessing, Susan Sontag, Louise Bourgeois, Shirley Jackson, Elizabeth Smart, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker and several others — and asks of them (and us): How do you make time for, much less nurture, creativity in the face of parenting? Ostensibly liberated, women artists aspire to make space for the imagination and the domestic. That the attempt to do both still feels like driving without a map is a testament to how slow and difficult social change really is.

Reading about these women of the last century brought me back to my own experience. Even before the pandemic, I was spending my days as the primary caregiver for my two children, then writing and editing over late nights. This “balance” of labor, women told me in no uncertain terms, just couldn’t be done. Some shamed me for what they saw as putting my intellect on the shelf instead of putting my kids in day care. Their admonitions resonate with Phillips’ idea that, for some, writing while mothering can feel as terrifying as leaving a baby on a fire escape.

I just wanted to see if it could be done, and one sure way to make anything possible is to tell someone it isn’t. After a long career in book publishing, freelancing atop full-time parenting was an experiment in creative living — in finding a rhythm while doing what mattered most to me. By the time of the first COVID-19 lockdown, I was wholly prepared for what blindsided most parents. I had — and this is Phillips’ theme as well — a different notion of time.

The subject is personal for the biographer as well. Phillips’ concrete plan “to explore the blank spot on the map where mothering and creativity converge” originated from her inability “to convey the full power of my own life as a mother.” For reasons beyond the sheer fatigue of parenting, it’s hard to distill the experience of mothers engaged in creative work.

Fortunately, Phillips is an expert distiller. Instead of developing complete portraits of the artists and writers, she works to connect themes and ideas. She knows when to tread lightly and keep the expository writing tight; she pulls examples that illustrate her points, leaving the reader hungry to dig further into novels and catalogs on their own. In her chapter on Ursula K. Le Guin, Phillips seizes on critical moments that illuminate the fantasy author’s determination to write while also maintaining a domestic life with deep ties to her parents.

While Le Guin struggled to be published, she came to find that fantasy or science fiction writing offered her a freedom to sublimate her engagement with social issues, as well as the graduate studies she’d forfeited for marriage. Motherhood, meanwhile, “allowed her to take imaginative risks … by giving her a place to come back to.” Phillips also closely tracks the ways Le Guin’s family, privilege and imagination helped her obtain and then bounce back from an abortion during her senior year of college. For 40 years, her secret informed her drive to devote equal energy to work and family. This fleet-footed chapter is 27 pages long.

In an equally taut closing chapter on Angela Carter, Phillips lands on the moments when the fierce tension between Carter’s longing for independence and love for her family feeds into her brilliant fiction. Of her final novel, “Wise Children,” Phillips notes, “The work of care alters time, linking humans to the past and future, tying us to the present, insisting on simultaneity, allowing moments of selfhood, committing us to nostalgia and futurity.”

The biographer closes by quoting Carter: “Truthfully, these glorious pauses do, sometimes, occur in the discordant but complementary narratives of our lives and if you choose to stop the story there, at such a pause, and refuse to take it any further, then you can call it a happy ending.”

Responding to the fallacy that creative life must stand apart from motherhood, Phillips asks, “What is the subjective experience of being a mother, and why, despite a steadily growing body of writing on the phenomenology of mothering, does it seem, on a deeper level, so unnarratable, undramatic, everywhere in practice, but in theory nowhere?” Why must motherhood be “all description and no story”?

Phillips aims to correct this in part by distilling the experience as an experience. “It’s keeping and letting go,” as she puts it. “It’s art and care going on at once, for a moment, a day, a lifetime.” And it leads to new ways of thinking about careers — about the rush toward accomplishment before the choice to become a parent. Rather than boxing up one’s life into distinct phases (the aspiration for a “5 under 35” award), why not reimagine the whole messy and imperfect trajectory of interruption and improvisation?

Elevating the work of elders and removing some of the shine from precocity is a start. “This book took too much time,” Phillips notes. “I started thinking about it when my children were in elementary school, and as I finish they are both in college.” And yet, what does it matter?

In her 1982 memoir, “Daybook” (which Phillips could have included), the sculptor Anne Truitt noted that “rationalization is a form of desperation. It takes kindness to forgive oneself for one’s life.” Creative mothers deserve to go easier on themselves, to travel at their own pace.

Phillips models this self-assurance in her approach. Too many recent biographies become bogged down in details, assembling evidence as though arguing at court. I prefer Phillips’ style. Her authority is built on knowledge and a mutually trusting relationship with the reader. This brings me back again to the instincts that have served me well (I hope?) in parenting. If you know yourself and listen closely to your child, everyone else’s opinions and perspectives are window dressing.

Fortunately, there are a number of excellent, unconventional books about motherhood being published this spring, including Angela Garbes’ “Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change” and Jazmina Barrera’s “Linea Nigra: An Essay on Pregnancy and Earthquakes.” Each makes short work of shredding traditional notions of success and productivity. As Garbes notes, “It’s messy to pull apart identity and worth, the home and public life, but maybe we can try and allow them to coexist, to find meaning in each of them.”

Phillips’ book is not just a cultural history; it is a testament to endurance and devotion. The entwined work of mothering and creativity is a volatile but illuminating gift. Would that everyone could see it that way.

LeBlanc is a book columnist for Observer. She lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.