Page-to-Screen: ‘The Power of the Dog’ is an ideal adaptation of a neglected masterpiece

“Phil always did the castrating.” So begins Thomas Savage’s neglected American masterpiece, “The Power of the Dog.” For decades, filmmakers tried to adapt it, and one can understand the challenge. The 1967 novel is a microcosmic tapestry of tribalism, outsider life and westward expansion packed into a single, slim volume. Yet its movement lies not in its limited action but in memories, daydreams and private pain.

Rather than attempt a complete screen translation, Jane Campion’s “The Power of the Dog” is a paragon of its own that honors Savage’s book. If there’s justice in the world, Campion and her film will take home the Oscars for adapted screenplay, director and best picture. But were there justice in the world, we would all have read Savage’s modern classic in high school.

What to know about ‘Dune,’ ‘Don’t Look Up,’ ‘Power of the Dog,’ ‘Drive My Car’ and other best picture nominees.

Like other books by the late Savage, this one wasn’t a commercial hit, but critics adored it and aptly compared it to work by Willa Cather. The novel follows sibling ranchers, the Cain- and Abel-like Phil and George Burbank, who encounter a working-class widow, Rose Gordon, and her teenage son, Peter. When George and Rose wed and she and Peter move to the ranch, Phil makes it his mission to drive them away. But when Phil recruits Peter as a pawn and protege, the story takes a turn.

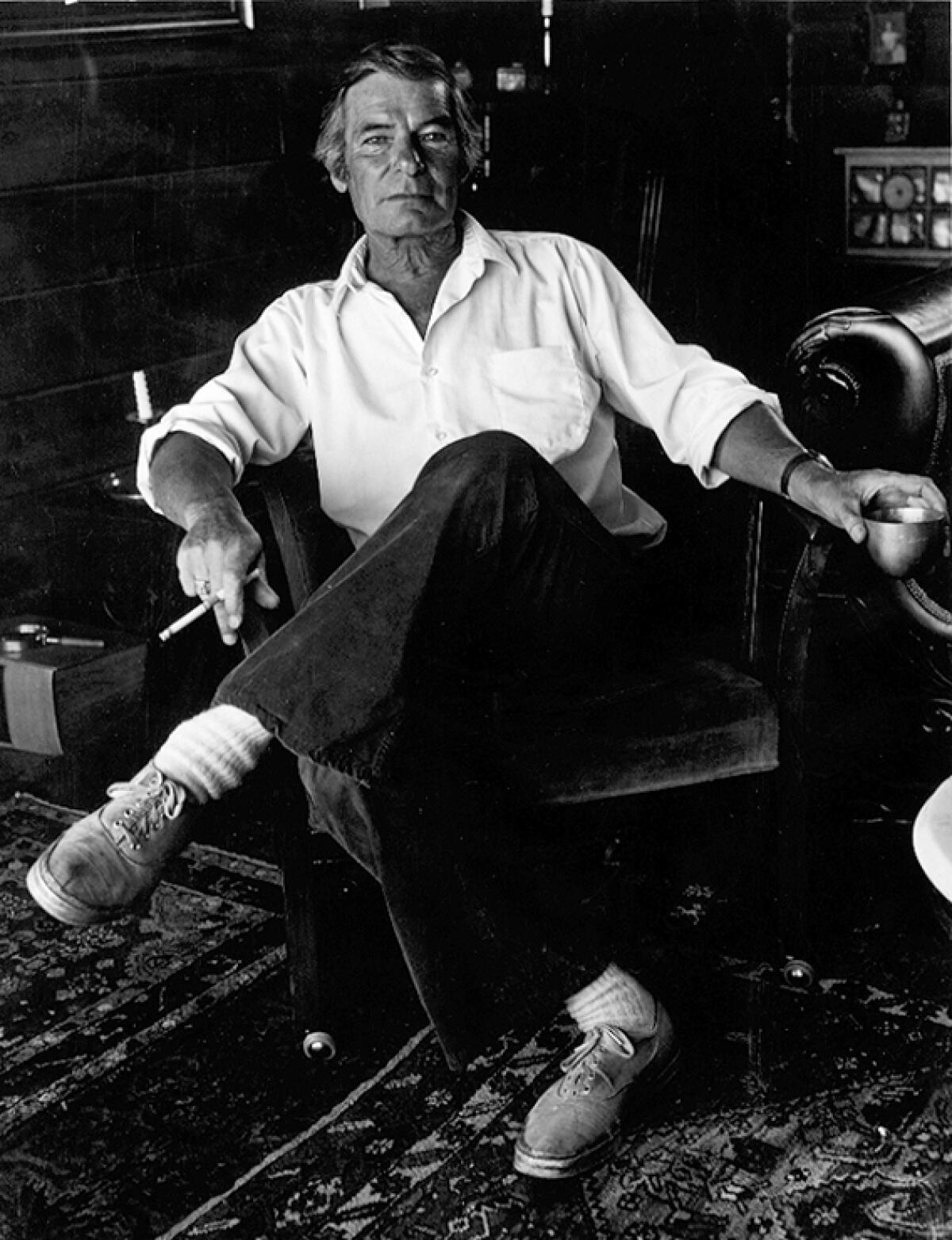

Much like Peter Gordon, Savage grew up on a cattle ranch in 1920s southwest Montana with his mother, stepfather and gifted but malevolent step-uncle. The last died from an anthrax-infected hand. While Savage centers on compelling menace Phil Burbank, the book’s free indirect narration acquaints us intimately with a host of minor characters — part of the story’s rich pleasure.

Most of all, we get to know the deeply humanitarian Johnny Gordon, father to Peter and husband to Rose. Like many under capitalism the world over, the Gordons fall prey to the whims of migration and urban development, a circumstance only avoided by those as wealthy as the Burbanks. Eventually, downtrodden Johnny is bullied to suicide by a Mephistophelean rancher (guess who), though Peter and Rose never learn the catalyst. Johnny’s absence deprives the community in ways that echo throughout the story.

The lives of the Gordons and Burbanks could’ve been fodder for TV. But serializing the story would have torn its delicate fabric and diluted its tension. Campion makes a choice, both necessary and bold, to relegate Johnny’s life and tragic death to backstory. She then embeds us within Team Gordon, beginning and ending her film with authorial avatar Peter. We therefore experience Phil as the frightening enigma he represents to others.

The novel demonstrates in even greater depth Phil’s desperate need to rule his fiefdom; his world is a monument to a lost love, and any change threatens it: technology, social progress, new housemates, growing up. He retreats to Neverland through a willow-branch hidey-hole. In the film, he smears himself with mud like a prairie Col. Kurtz. It’s an effective image of Phil, cultivating his own isolation.

“I probably won’t know what to think about this for another five years,” the writer-director of the noir western says of all the attention her film has received.

In both the book and Campion’s film, Phil brings up his dead mentor, Bronco Henry, early and often. It’s clear from the jump that Phil was in love with him: the butchest cowboy who ever roamed the range, the man who taught him to braid rawhide. A less confident filmmaker might have used flashbacks or voice-over, but Campion keeps their history exactly as elliptical as Savage does, stoking its untouchable power. She does so by externalizing the book’s subtle allusions. Now their relationship lives on in a collection of mementos: A monogrammed scarf, soft-core muscle man rags and Henry’s saddle, where young Peter will sit, make Phil’s longing tangible.

Just as Campion selects specific misdeeds of Phil’s to stand in for the brutal lot, she lights upon a rabbit to illustrate Peter’s dispassionate dealings with death. And when Peter offers his rawhide to Phil, the pair’s final scene is erotic as hell, checking off about five different fetishes. (Later, Peter holds Phil’s rawhide rope tenderly — through a latex barrier.) Campion also improves on Savage’s ending by slipping key clues into earlier moments of the film. No longer spelled out, it’s now of a piece with the creeping revelations in the rest of the book.

Campion’s other films — replete with landscape photography, period drama and cat-and-mouse games — have prepared her for the challenges and rewards of adapting Savage’s novel. “The Piano” and “Portrait of a Lady” conveyed new brides’ misery in inhospitable homes, the latter adapting a highly interior text. More surprisingly, the Burbank sibling relationship harks back to her 1989 gem, “Sweetie.” In that film, the protagonist’s sister refuses to exit childhood, sucking all the air out of every room she enters. (Geneviève Lemon, who played the insufferable Sweetie, here appears as the Burbanks’ maid.) Unusual for a comedy, “Sweetie” resolves in a merciful death.

It’s hard not to view “The Power of the Dog” as an adult cousin to Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain,” which adapted the romance by Annie Proulx. Proulx wrote an afterword for the 2001 rerelease of Savage’s book, in which she surmised that the author didn’t make explicit the sexual bond between Phil and Henry because a “serious novelist” couldn’t back then.

And yet there was already a clear lineage of more overt — and perfectly serious — queer novels. The book followed 25 years of classics by Carson McCullers, James Baldwin, Christopher Isherwood, Jane Rule and others. Savage’s publisher even compared him to Truman Capote. Phil’s machismo invokes John Rechy’s “sexual outlaws” from “City of Night” (1963); “Brokeback Mountain” co-screenwriter Larry McMurtry was among Rechy’s champions.

The “Power of the Dog” director was praised and criticized for remarks she made at awards shows over the weekend.

Savage’s reality was more complicated. He was married with kids, out to his family and, by all accounts, happy that way. He dedicated “The Power of the Dog” to his novelist wife, his first reader. Contemporaneously, he abandoned a story about his recent affair with Tomie dePaola, who went on to write dozens of children’s books including “Strega Nona.” It seems that in his career and life, Savage essentially chose between worlds but let his characters reflect ambivalence.

Campion respects his irreducible book: She doesn’t try to diagnose Phil. While he has the story’s leading role, Peter is its hero. Their respective players, Benedict Cumberbatch and Kodi Smit-McPhee, deserve Oscars for their sensitive portrayals of complex characters in an evolving pas de deux. Watch the film to sample the spirit of Savage’s story, then read his elegant saga of American malaise. On a perfect Oscars night, we’d all have someone with whom to braid hides. On this one, a trough of awards for “The Power of the Dog” will do.

Johnson’s work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, the Believer and elsewhere. She lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.