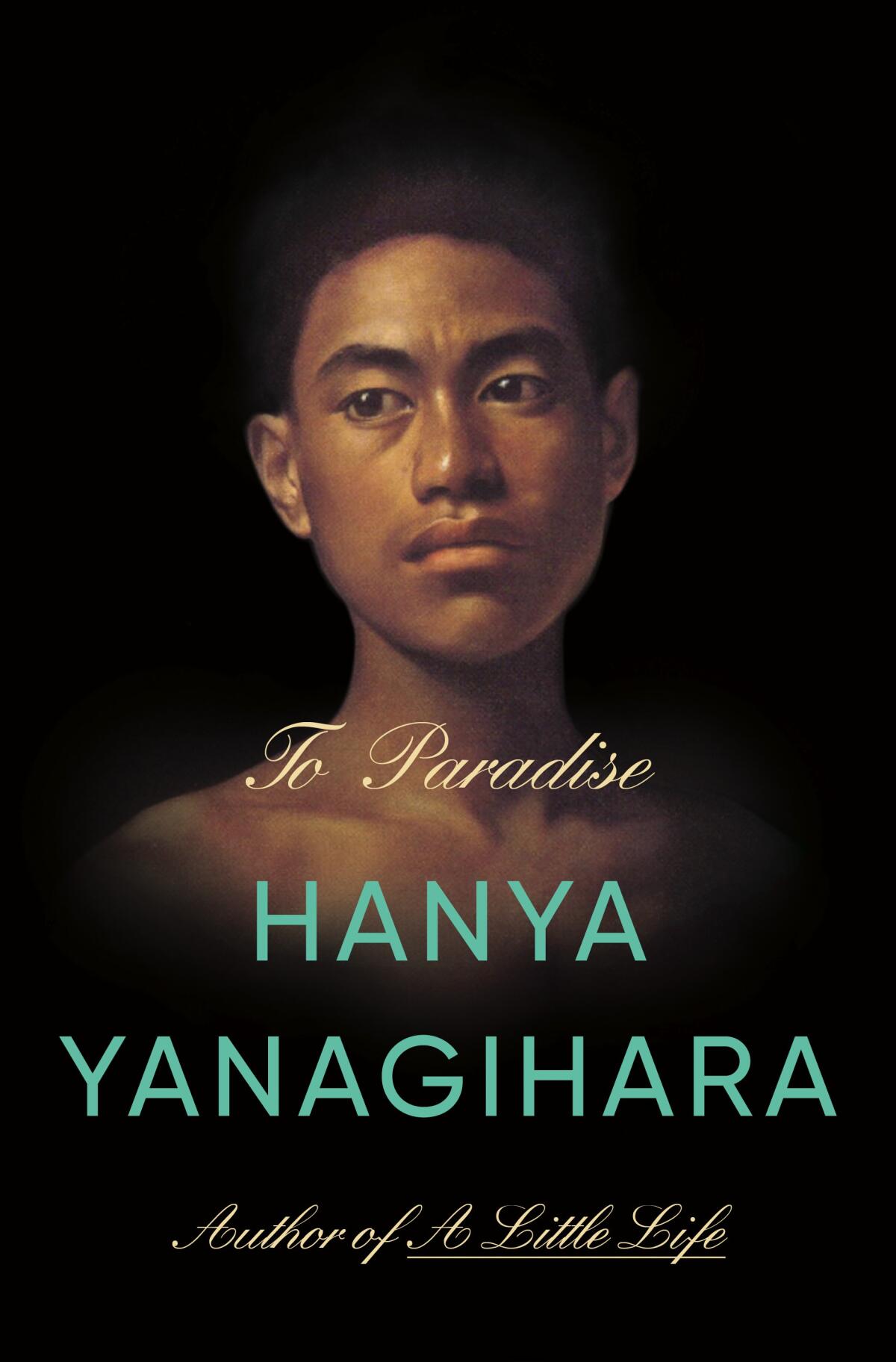

Review: Hanya Yanagihara’s new novel proves her reputation for ‘empathy’ is all wrong

On the Shelf

To Paradise

By Hanya Yanagihara

Doubleday: 720 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Writing a novel is, in part, an act of manipulation and seduction, a give-and-take, a dance. In 2015, Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life” seduced millions. It was a finalist for the Booker prize and the National Book Award. T-shirts were emblazoned with the names of the four main characters. I read the novel, an 816-page New-York-friends melodrama that devolves into near-constant pain and trauma, on a plane, and I sobbed. In contrast to her 2013 debut “The People in the Trees,” Yanagihara’s follow-up had beautiful people, Harvard, the New York art world, money, fashion, architecture. And so much pain. Elif Batuman aptly compared it in the New Yorker to “Sex and the City” but with suffering.

“Empathy” was the word used most often in reference to the novel. Empathy is not the sole or even the most interesting goal of art, but it is worth exploring what critics have decided is a defining attribute of Yanagihara’s work. In fact, feelings in “A Little Life” were mostly flat and blunt force — the same notes hit hard over and over. It was almost chemically addictive, but it lacked the complexity and texture of an empathic piece of art. “To Paradise,” Yanagihara’s third novel (out next week), feels like further proof that her greatest strength lies in finding new ways to seduce her readers, while calling into further question the value or the purpose of the lure.

“To Paradise” is broken into three sections over three centuries: 1893, 1993, 2093; in each the world is ours but tilted. In none of them are all 50 American states united; societal precarity and authoritarianism become amplified over time. In each section, Yanagihara has an anthropological brilliance for compiling and disseminating objects, signifiers, settings. She can establish, immediately and engrossingly, both our characters and their worlds. And while in “A Little Life” we are gradually ratcheted in only to be barraged by trauma, in “To Paradise” the players and the conflict are laid out, the gloomy foregone conclusion suggests itself — and then we move on to another time. Every section ends with the words “to paradise,” and each time we know the characters are likely headed for the opposite.

In the first section we meet David (30s, wealthy, orphaned, lives with his grandpa). He has an illness; he sometimes takes to bed. He’s the oldest of his three siblings but the only one still unmarried, and his grandfather has set up a possible arranged marriage for him with Charles, a wealthy older man. One of the ways this world is tilted is that in this New York, David can marry the person whose gender most appeals to him. New York is a member of the Free States, which are “liberal” in sexual terms but still classist and still racist (this at least feels familiar). The problem is that he falls in love with Edward — broke and aberrant, charming, younger, almost certain to break his heart.

I’ve read a lot of emotionally taxing books in my time, but “A Little Life,” Hanya Yanagihara’s follow-up to 2013’s brilliant, harrowing “The People in the Trees,” is the only one I’ve read as an adult that’s left me sobbing.

The second section opens similarly, and with similar names: a young, misguided David, an older, wealthy Charles. They are not visibly connected to their namesakes, except that the action revolves around the same townhouse in Manhattan’s (and Henry James’) Washington Square. It’s 1993 and AIDS is rampant. Charles is throwing a party for a friend who is dying. David gets a letter that evokes memories of his Hawaii childhood.

In the last section, it’s 2093, and the pandemic-ravaged dystopia is both proximal to ours and far more extreme. There are two braided timelines, a Charles and a Charlie. The world is bleak, authoritarian. Charlie (female, 30s) is in a heterosexual arranged marriage, sterile and emotionally distant as the result of a drug that saved her from a virus that was especially brutal to children 24 years earlier. Her grandfather, Charles Griffith, is perhaps the most complicated character of the whole book. An architect of some of the state’s most nefarious projects, Charles is also Charlie’s devoted and loving protector. He is one of the few in the novel who’s drawn as both victim and perpetrator at the same time.

Because each story breaks just as, in another book, it would be getting into the specific muck and murk of living — daily interactions, contradictions, complexity, consequences — it feels important to consider how each section works (if it does) toward a greater whole. In part, Yanagihara accounts for these irresolutions through the repetition of names and concepts across the timelines: the Davids and the Charleses but also Edwards (charming and seductive) and Peters (lovers turned intimates); long letters unspooling events and relationships; children often raised by grandparents. Through this we experience the pleasure of recognition and some simulacrum of connective tissue, even if when we step away the impact or import of all this tethering never comes to much.

Almost every David is given at least one opportunity to break out of the stifling system he lives in — to escape his family for a lover or a revolution — but, in each instance, the book refuses these characters the intelligence, the agency or the page count to do it. Their narratives come to feel less like people making choices, taking actions, and more like set-pieces moved through the book’s architecture to converge on a preestablished point.

What “To Paradise” seems mainly to argue is that paradise is an absurd concept, exclusionary and dangerous and fatally self-deluding. This is on clear display in the sole section in “To Paradise” in which we actually glimpse a paradise. The second half of the middle part, it’s the only time we’re not in New York: a flashback to 20th century David’s childhood in Hawaii in which his dad (also a David, though they both use the Hawaiian version, Kawika) was tricked by an Edward into giving up his life to live on uncultivated family land.

Flawed but engrossing, the craft of HBO Max’s post-post-apocalyptic tale masks its narrative imperfections: As in the Bard, plot gives way to poetry.

This particular Edward is meant to be a seductive character. He’s a revolutionary, a Hawaiian secessionist. The elder Kawika is compelled by him since childhood, but his choice to give up his whole life, including his son and mother, for this idea makes no sense even to him. “We were inessential in every way,” he writes to his son later. “We were playacting, and because our pretending affected no one — until of course it did — we could be as indulgent as we wanted. ... In reality we did nothing — we didn’t even try to plant the forest we wanted.”

This is Yanagihara’s single opportunity to make paradise something other than a concept, however destructive and absurd — to make us understand its hold on the desperate psyches of the Davids and to see not only their frailties but the thrill of their compulsions, such that the book might remind us that these same compulsions, these same frailties, are also sometimes ours. Instead, the section borders on the comical. David’s choice is so obviously nonsensical, proof of a willful ignorance so profound that its proponent, Edward, seems to die of madness and its disciple, David, eventually wills himself immobile and blind.

……

I didn’t finish reading “A Little Life” on that airplane. The book is long. Back home, when I read the scene near the end in which a pivotal and beloved character died for what felt like no good reason, I threw the book against my bedroom wall. I had gone a long time with that book because it offered so much feeling — trauma as an access point to a deeper understanding of something about being human. But that moment helped me see how simplistic, how seemingly disinterested in actual humans, “A Little Life” turned out to be.

The sheer scope of “To Paradise” also makes it feel Big and Important, as if it has no choice but to say something about who and what we are. But here’s the thing about seduction, at least the type I like: Questions are posed, new layers are added, space is made for the reader to feel uncertain, uncomfortable; there’s room — an imperative, even — for surprise. What Yanagihara offers instead is the version that feels good until you look too closely, until you wake up the next morning — as after a Lifetime movie or a late-night Tinder date — and find that the endpoint was predetermined and that there’s precious little in its wake. It was Bigness, sure, full of sound and fury, but devoid of specificity or self-doubt or, indeed, of empathy.

Novelist Lynn Steger Strong on the revolutionary passivity of Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh and Sally Rooney — how we’ve misread them and what comes next.

Strong is a critic and the author, most recently, of the novel “Want.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.