Review: Siri Hustvedt’s powerful essays on family and art focus on what’s missing

On the Shelf

Mothers, Fathers, and Others: New Essays

By Siri Hustvedt

Simon & Schuster: 320 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The cover of Siri Hustvedt’s latest collection of essays, a self-portrait by the artist Louise Bourgeois, depicts a childlike figure standing inside a Janus-faced head. The profusion of Freudian imagery matches the title of the book as well as its subject matter: “Mothers, Fathers, and Others.” Hustvedt, the author of seven novels, has also published several papers on neuroscience and psychoanalysis and is a lecturer in narrative psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

The essays herein, most of them previously published, range from the personal to the critical, and they often encompass the clinical. Hustvedt brings a surprisingly scientific approach to her artistic and literary subjects. In “What Does a Man Want?,” on the origins of misogyny, she argues that a fixation on DNA and the genome (and the stance that life begins at conception) overlooks the essential influence of gestation. “By assigning a godlike role to genes,” she writes, “the ‘right-to-life’ forces have adopted science in their service and effectively denied the reality that a female body is crucial to fetal development.”

She illustrates the erasure of the female body through the example of the placenta. “How can a human organ go missing in plain sight?” she wonders as hers is whisked away after the birth of her daughter. “The placenta is the least understood of all human organs. It has been called forgotten, ignored, overlooked, mysterious, underappreciated, and even the ‘Rodney Dangerfield of organs.’” Not to mention that birth itself is a “subject missing from the canon of Western art.” Here is Hustvedt’s unique contribution and genius: By bringing a placenta into a fight about misogyny, she fortifies her argument with physical evidence.

Catherine McCormack, a course director at Sotheby’s, talks about her new book, “Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies.”

Outside her scientific knowledge, much of what fascinates Hustvedt could be defined as what’s missing. “Wuthering Heights,” for some, is a study on the horrors of heredity. But for Hustvedt, it’s all about Catherine’s inability to tell her own story, dead or alive. “Persuasion” is Jane Austen’s takedown of male narratives of “fickle women.” “Men have had every advantage in telling their own story,” Anne Elliot tells Captain Harville as former suitor Wentworth listens in. “Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.”

Other pieces in the collection don’t fall short, exactly; it’s more that they fall out of place. Two essays about living in New York during pandemic closures, “Notes From New York” and “Reading During the Plague,” feel like exercises. After the vulnerability displayed in more probing personal essays such as “States of Mind” and “Mentor Ghosts,” these fail to resonate.

When Hustvedt returns to the idea of what’s missing, her writing takes off. In “Both-And,” an essay on Bourgeois, she offers the concept of intercorporeality from French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “that human relations take place between and among bodies, that we perceive and understand others in embodied ways that are not conscious.” What could be more loaded than the mother’s body, a body that is not one, but two? A body that is no longer hers alone? “The artist sees the object unfold, a thing that rises out of you, is related to you, but is not you either,” Hustvedt writes about Bourgeois’ work. But this easily applies to birth and mothering.

For all these sensitivities, Hustvedt’s most personal piece, “A Walk With My Mother,” dwarfs the others in this collection. In concert with the scientific essays, it is intensely focused on the physical. The intimacy between Hustvedt and her mother is unusual. But Hustvedt’s passion for that intimacy is nothing short of radical.

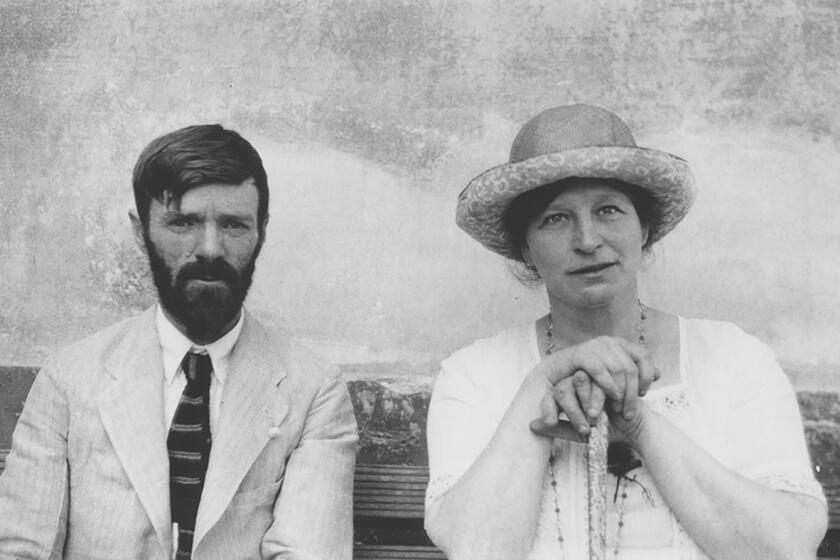

A new Lawrence biography, “Burning Man,” by Frances Wilson, and Rachel Cusk’s novel “Second Place” turn the toxic male author into rich material.

As a child, Hustvedt thought of her mother as the personification of “comfort, safety, happiness.” While the physical closeness changed as Hustvedt got older, she writes, “my mother and I embraced and caressed each other until the end of her life. When she was really old, I would often lie beside her in bed and gently rub her arm.” That closeness is afforded, in some ways, by her father’s death. “A woman in her eighties and a woman in her fifties spent time together because they really wanted that time together.”

So much of her mother’s strength is illustrated through her physical body. After undergoing a mastectomy, her mother told her, “I want you to see it.”

“She removed her blouse and her bra and showed me the long scar where her breast used to be. Her forthright display of the healed but ugly wound had a powerful effect on me,” Hustvedt writes. “Bodily mutilation is no small thing. I can still see her standing opposite me with her erect posture and resolute expression on her face.”

Hustvedt takes solace again in absence: her mother’s amputated breast, a wound both psychic and physical. Her mother’s desire to show her what is missing, and Hustvedt’s eagerness to look, is the basis of their intimacy — and for Hustvedt, in these essays, it is the basis of knowledge and feeling. “A Walk With My Mother” could easily be an entire book, one I would eagerly devour. As Hustvedt writes, “Mothers are punished for what they feel or don’t feel.” The missing piece ultimately tells us more than the canonical body could ever hope to say.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

First celebrated, then jailed, he wrote ‘1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows’ to honor his father and ensure his son knows ‘what life means to me.’

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.