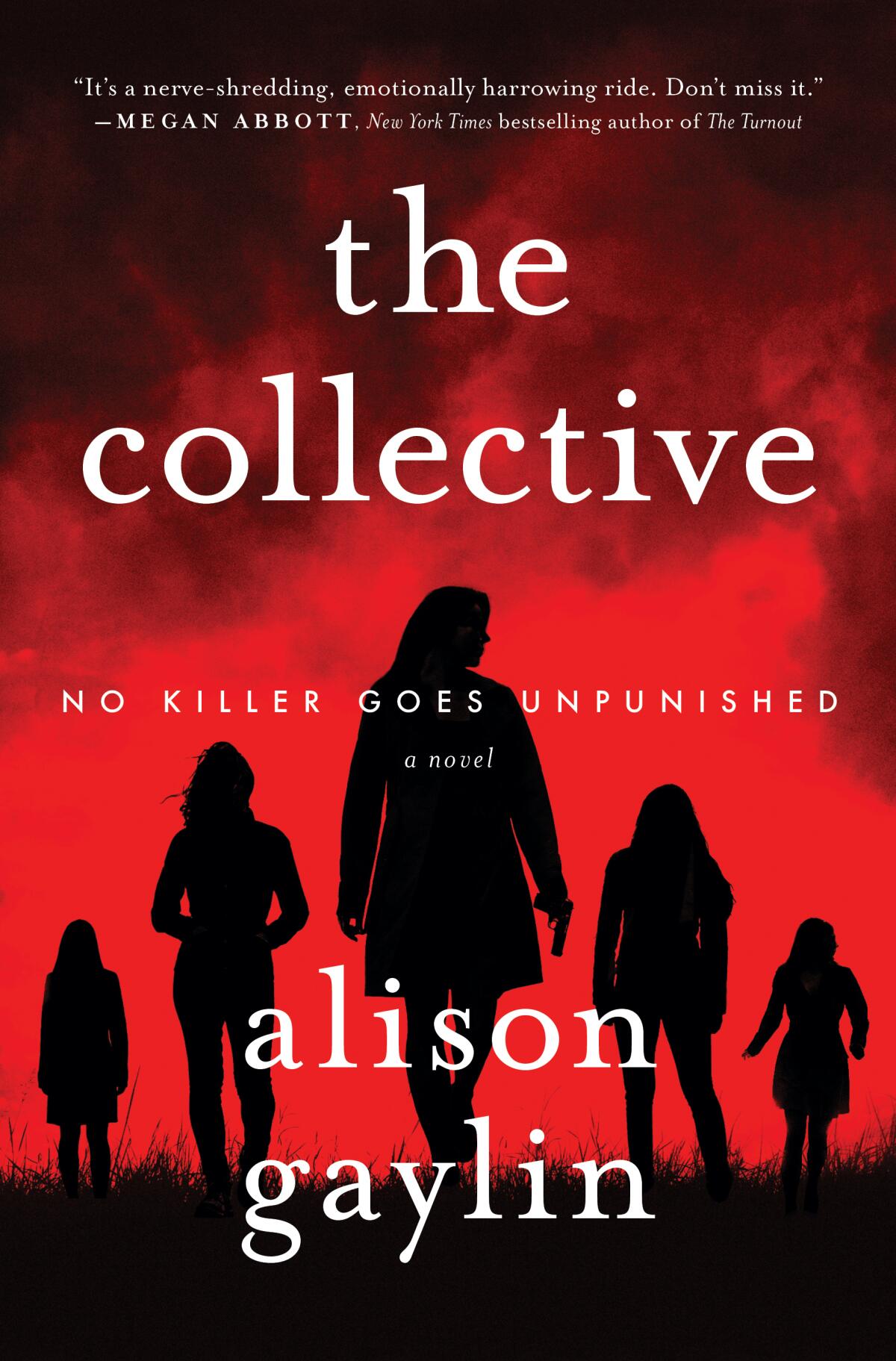

Review: A mother gets a shot at revenge — at a price — in Alison Gaylin’s ‘The Collective’

On the Shelf

The Collective

By Alison Gaylin

William Morrow: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We may be drowning in the salacious details of the murder du jour via TV news, true-crime podcasts or self-anointed Twitter sleuths, but how much of that media attention is focused on the loved ones left behind? If their anguish is touched upon, it tends to come in small, easily digestible doses, perhaps out of fear that bottomless grief and rage might be contagious.

Alison Gaylin, acclaimed author of the “Brenna Spector” series, marches boldly into that void in her new thriller, “The Collective.” Like “If I Die Tonight,” Gaylin’s Edgar Award-winning novel about a hit-and-run death, “The Collective” kicks into gear in the aftermath of a teen-on-teen murder — that of Emily Gardener, who at 15 is brutally raped in the Hudson Valley woods near a frat house at Brayburn College and left to die in the bitter January cold. Despite Emily’s dying declaration to her mother that her attacker was 17-year-old Harris Blanchard, “the rich golden-haired boy with the angelic blue eyes and the premed major” is acquitted at trial; five years later, he is about to receive a humanitarian award at a Brayburn alumni dinner.

Times Book Prize finalists Rachel Howzell Hall, Ivy Pochoda, S.A. Crosby, Jennifer Hillier and Christopher Bollen talk about race, place and genre.

Crashing the party is Emily’s mother, Camille. Now living alone in a small town, divorced from Emily’s father in the traumatic wake of the trial, she’s an overmedicated, haunted husk who admits she’s unrecognizable. “I’ve stopped coloring my hair and wearing makeup and I had the bolt-ons removed, and so I am literally no longer the woman I once was,” she narrates. Somehow notified of the event honoring Blanchard, Camille shows up, mixes alcohol with her meds and is soon unable to stop herself from a raging assault, which lands her in jail.

Camille is bailed out by Luke Charlebois, a successful actor on a television police drama who has an intimate connection to her family. Other people, friends who remember the case or strangers who saw her assault via smartphone camera, glibly advise her to “just move on” — all except an older woman who shows up outside the precinct, pressing a business card on Camille from a group “for people like us.” The card’s only word, “Niobe,” may ring a bell for readers of Greek mythology: Niobe had such overweening pride in her twelve children that the Titan Leto sent her own children, Apollo and Artemis, to kill all of them. Niobe’s grief turned her into stone, her tears into waterfalls.

Propelled by the woman’s uncommon empathy, Camille ends up in a private Facebook group and, as her grief hardens into unquenchable anger, on a dark web site for women whose children were killed — girls dead from fentanyl administered by rich boyfriends; a (presumably Black) boy shot for walking in the wrong neighborhood; a kindergartner felled in a hit-and-run accident — and their assailants never brought to justice.

“Razorblade Tears,” S.A. Cosby’s follow-up to the Times Book Prize-winning “Blacktop Wasteland,” follows two men hunting the killers of their gay sons.

Gaylin’s prose, so achingly pure yet electric in its gathering rage, pulls readers so far into the abyss in which these women live that it feels entirely plausible when Camille writes, “I want him dead. For real. I don’t care how,” and the site’s admin asks if she truly means it. What follows is Camille’s initiation into “the collective,” an all-female sorority of sorts that makes its members’ revenge fantasies come chillingly true — but not without an enormous price. It’s that cost — moral and also physical — that pushes the story forward. Along the way, readers may be prompted to ask: Are evil acts always reflective of evil hearts, their perpetrators forever beyond redemption? Is there any way to atone for one’s mistakes, no matter how grave?

Full of twists, “The Collective” also raises fascinating questions about the echo chamber of social media and the righteousness of rage — maternal or otherwise. Even after reading its shattering conclusion, you might be drawn back to the beginning of this blistering novel in search of every last breadcrumb Gaylin has dropped, beginning with its powerful epigraph from Euripides’ “Medea,” a tragedy about another mother driven to violence: “Hate is a bottomless cup; I will pour and pour.”

Woods is a book critic, editor and author of the “Charlotte Justice” series of crime novels.

‘State of Terror,’ by the former secretary of state and the crime novelist Louise Penny, benefits from the partnership of two very different authors.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.