A conservative’s biography tears down Robert E. Lee. But he’d rather leave the statues up

On the Shelf

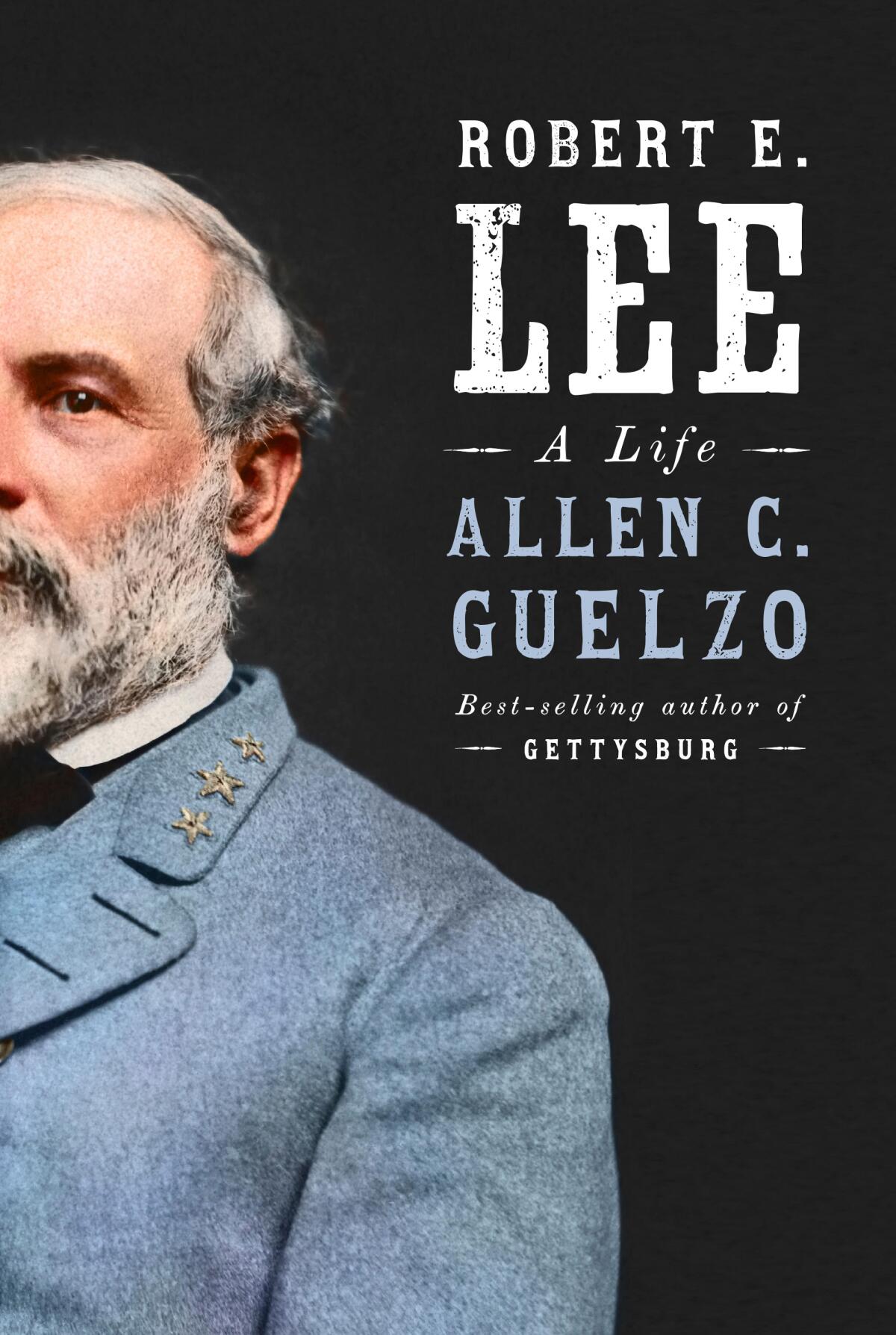

Robert E. Lee: A Life

By Allen C. Guelzo

Knopf: 608 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

As a historian, Allen C. Guelzo is acutely aware of how perceptions change over time. When he started his latest biography, “Robert E. Lee: A Life,” back in 2014, “Lee was a different person,” he says. “I was writing in B.C., Before Charlottesville.”

As an outspoken conservative, Guelzo is also aware how perceptions of his work might be shaped by the times, especially amid debates over the removal of monuments honoring Confederates — chief among them Gen. Robert E. Lee.

“There’s some apprehension on my part,” says Guelzo, the author of numerous books about the Civil War, most focusing on Abraham Lincoln. His Lee biography was attacked on Twitter as pro-Confederate before he had even finished it. “At one point I asked my editor, ‘Should we just put this in the freezer and wait several years?’”

Those concerns were heightened last fall after he participated in the White House Conference on American History, which liberals and most historians called culture-war propaganda aimed at boosting Donald Trump’s reelection chances.

“Shame on Guelzo for lending himself to that stunt and helping profane the National Archives,” tweeted Yale historian David W. Blight, referring to the revered institution where the conference took place.

Guelzo defends his attendance, saying it wasn’t a campaign event and Trump didn’t speak until he was gone. But Ben Carson decreed, “I think I speak for all of us when I say how blessed we are to have a leader like President Trump,” while panelists condemned Black Lives Matter “riots.”

The author would not directly answer the question of whether participating was a mistake, instead complaining about unpleasant responses and blaming anti-Trumpers for making an issue out of it, saying “there’s a certain paranoia at work.”

In any event, on the topic of Lee, he is sure of being on the right side of history.

“This is somebody who committed treason,” says Guelzo, who is both the son and father of career Army officers. “Robert E. Lee raised his hand against the Constitution he’d sworn an oath to defend. I take that seriously.”

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey always wrote of public pain and private struggle. Her memoir, “Memorial Drive,” lets her mother speak.

His biography examines why Lee betrayed the Union he had faithfully served, and it is not a flattering portrait. It is certainly a detailed one. Guelzo doesn’t reach Lee’s monumental series of decisions — to turn down leadership of the Union Army and ultimately to take command of the Confederate forces — until page 180.

Instead, he carefully lays the psychological groundwork, showing how Lee’s childhood and his three decades in the Army — mostly “a fairly humdrum career” as an engineer — made those mistakes feel inevitable.

Guelzo says Lee’s father, who abandoned the family early on, was “a walking embarrassment who makes the name Lee stink.” Driven to redeem the family legacy, Lee became a perfectionist. As an engineer, “he could control materials in a way he couldn’t control people who populated his past,” Guelzo says.

Craving fiscal independence and still viewing himself as poor even after he inherited money from his mother, Lee put financial security first and foremost. This was his undoing, Guelzo argues — without dismissing Lee’s political and racial views as unimportant.

In the years before the Civil War, Lee was vocally pro-Union and called slavery a “moral and political evil.” Nonetheless, he enslaved people, had them brutally whipped and thought of them as less than human. He was, in Guelzo’s framing, a standard issue mealy-mouthed Virginian.

“Lee knows in his guts this is wrong but he’s not going to do anything about it because no one else is doing anything about it,” says Guelzo. “The ‘I hate slavery but…’ and the ‘We have to wait for time and God to take care of it’ lines were constant in the Upper South.”

Lee was ultimately driven by the desire to preserve his wealth by maintaining control of his family estate in Arlington, Va. That’s what was foremost in his mind when considering competing offers from the Union and the South. He was not a deep thinker, Guelzo says, merely someone so caught up in self-preservation that he never fully weighed the impact of each step he made.

“He’s just making incremental decisions and then, bang, he’s in command of these forces and he’s a traitor,” says Guelzo.

California confronts its racist, colonial past as statues fall, mascots are renamed and a town debates changing its name that honors a Confederate general.

The author also punctures the halo of Lee as a great general. At best he was a sharp strategist. “He understands the Confederacy cannot go 15 rounds and must score an early knockout, that’s why he’s so eager to carry the war across the Potomac into the North.”

But Lee was disinterested in battle tactics, deferring to subordinate generals like Stonewall Jackson; when they died, his flaws were revealed. Guelzo adds that he was weak on operations, unwilling to push back against the politicians to ensure that his troops had the supplies and support they needed.

After the war, Lee publicly conceded the loss and acknowledged that emancipation was the rule of law. But then he backtracked, calling Reconstruction “a farce” and adding fuel to the “Lost Cause” mentality that has since inflamed the South for 150 years.

Guelzo is thoughtful about Lee’s posthumous legend — the mantle of personal dignity in defeat that “spread a sacred canopy over the Confederacy” and became “an important commodity for the Lost Cause. With Lee they can say success is not the only measure of human worth.”

Beyond Confederate apologists, he adds, great Southern writers like William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor ended up exploring the idea of retrieving something worthwhile from failure.

On more contemporary matters, Guelzo himself has been accused of flirting with apologia. He refused to endorse the wholesale removal of Confederate statues, including those of Robert E. Lee. He would never support putting up a fresh Lee monument, but “being a history person, my instinct is always to preserve,” he says. “What I fear in public treatments of history is the resort to impulse and immediate anger.”

He makes sure to note that the man who gave the speech at the unveiling of the Lee monument in Richmond (the one torn down earlier this month) had fought to stop the Ku Klux Klan. He neglects to mention that many of its strongest proponents conceived it to uphold what one called “the superior race.”

“With monuments there are always complexities,” Guelzo says.

Crews remove one of the country’s largest remaining monuments to the Confederacy, a towering statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Va.

But as his biography ends, the author pushes past the nuances to make sure the ultimate point does not get lost: Lee was guilty of treason.

In fact, in his final verdict. Guelzo goes one step further. “If I had been wearing a blue uniform and I had Robert E. Lee come into my gun sights,” he says, “I would have killed him.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.