He fought in the Marines and MMA matches. A novel about his mother was the fight of his life

On the Shelf

The War for Gloria

By Atticus Lish

Knopf: 464 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 2014, Atticus Lish’s debut novel, “Preparation for the Next Life,” was published by a small press. Moving and often haunting, it told the story of a traumatized veteran and an undocumented immigrant making an unexpected connection in New York City. The rapturous reception that followed included the 2015 PEN/Faulkner Award and predictions of future glory.

This month, Lish publishes his second novel, “The War For Gloria.” The world is a very different place seven years later, and the book is a very different one too — consumed, as we are, with conversations about familial responsibility, health care, toxic masculinity and excessive policing. It’s also a much more personal book, because the author too has changed.

“Writing ‘The War For Gloria’ was the most challenging thing that I have done in my life,” Lish said during a phone call from Pasadena, where he and his wife recently moved. “And I suppose it transformed me, and that is worth a novel in itself.”

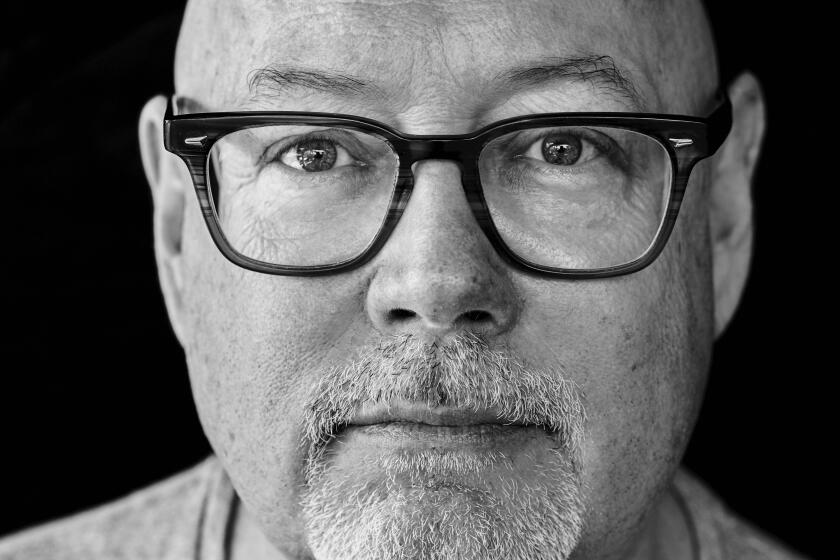

Lish knows challenges. He is a retired Marine, a veteran of blue-collar work and a sometime competitor in mixed martial arts tournaments — which give “Gloria’s” MMA scenes some added gusto. But revising a follow-up to an acclaimed novel involves a different set of skills.

For instance, Lish had to jettison an entire subplot involving a serial killer. But most challenging was pinpointing the source of his protagonist’s pain and guilt, which was Lish’s own. Describing that process prompted the author to pause a few times during our conversation, overwhelmed with emotion, as he explained that the only way to finish the novel was to keep going.

Klay, a veteran and author of the National Book Award-winning story collection “Redeployment,” follows up with the rich, complex novel “Missionaries.”

At the heart of “The War for Gloria” is the relationship between a mother and her son. Gloria Goltz is raising Corey on her own under difficult circumstances; at times they’ve lived out of a car. By the time Corey is in high school, their lives have become more stable — until the point Gloria is diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

This prompts Corey’s father, Leonard, to return, and leads Corey into a tense friendship with Adrian, a young misogynist obsessed with math and fitness. It’s not spoiling much to say neither one is a particularly positive influence on the teenager.

“The thing about human beings is, they’re tough enough to die slowly, which is exactly what my mother did.”

— Atticus Lish

Corey is forced to come of age on an accelerated schedule, desperate to find a purpose and a means of survival in school, through MMA fighting and in a series of construction jobs. Much of the material emerged from observation and experience.

“The fight between Corey and the guy that I called Jack — that is based on something that I saw at the Soboba Indian Reservation, at the King of the Cage promotion back in the 2000s,” Lish said.

Specifically, he recalls a fighter named Victor who took a brutal beating. As soon as Victor came into the ring, “the other guy dropped him with one punch and started hammering on his head,” Lish said. “So Victor rolls out and manages to submit him with something like under a second to go. I don’t think he could have survived another round.”

For Lish, it was a transcendental moment: “It did something to me physically. I jumped out of my seat.” After the fight, Victor spoke to Lish. His head was “all swollen up, and he turned to me. He said, ‘I’m a cockroach; you can’t kill me,’” said Lish. “I’ll never forget him saying that. I don’t know what became of Victor, but it was truly a display of heroism.”

Heroism takes many forms in “The War for Gloria,” chief among them its title character’s struggles with ALS. It’s here that Lish had to contend with his past — his own mother’s death from the degenerative disease. In conversation, he brought up a scene from “Rocky Balboa” in which Sylvester Stallone says, “There’s still some stuff in the basement.”

“Well, there was something in the basement [for me] very obviously,” Lish said. He had spent his teenage years wrestling with both the impending loss of his mother and the budding ambitions of any kid trying to define himself. He had not only survived but thrived, but his grief and guilt weren’t fully resolved. He knew, sitting in his writing room in Brooklyn, that he had to write his way through the conflict.

“I never talked about that to anybody except my wife,” he said, “so I launched into that and — the funny thing is, in the book I had never managed to say what I feel so guilty about.” He had tried to talk it through with others who might understand his dilemma, including Elliot Ackerman, a fellow author and Marine vet. But in the end, only the writing solved the problem.

It had to do, he said, with reconciling the idea that every act of endurance has a breaking point — training, writing, caring for a loved one — with a very different concept, the notion that absolute love is boundless. “I can get on a treadmill and I can make myself run,” he said. “And within two minutes, if I push up that tempo fast enough, I can rationalize quitting. And I’ve watched myself do it, you know?” He’d done it in Marine training all the time, and he was doing it now.

“I pushed myself to a breaking point several times in the course of writing the book, and therefore had to face failure and pick myself back up again,” he said. “And I suppose what I learned from that is that life would be easier if we all just had one breaking point. The thing about human beings is, they’re tough enough to die slowly, which is exactly what my mother did when she had ALS. It took her seven years to die.”

People don’t have only one breaking point, he realized. “You get worn out, you get your wind together and then you continue.”

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey always wrote of public pain and private struggle. Her memoir, “Memorial Drive,” lets her mother speak.

Though most of the novel was written in New York, Lish’s research involved extended trips to Boston. For a while, he worked there for a friend’s moving company. “I made some decent money while I was up there,” he said. “And I rewrote the book, which needed rewriting.”

The final third came together last fall, in correspondence with Jordan Pavlin, the editor in chief of Knopf. “It was a pure pleasure to see the rigor and care he brought to every aspect of the book as he revised,” Pavlin said. “The novel is fierce, but Atticus himself is exceptionally gentle, intensely attuned to every aspect of his characters’ unruly emotional lives. His ability to wrestle all of that pain on to the page is simply stunning.”

The final sticking point was a serial-killer crime thriller overlaid on the book — and at the core of that, a portrayal of the father, Leonard, that created emotional distance by villainizing him. Pavlin advised him to pull it out.

“Her words were, ‘You turned him from somebody who isn’t just monstrous into somebody who’s a monster. And if you have the endurance, you might want to rethink that.’ And I said, ‘OK, challenge accepted,’” he recalled.

He made one final push but not for himself.

“It’s great to derive a therapeutic effect from writing, but really there’s something more that matters,” Lish said. “Which is, can you create an object of beauty that other people will get something out of?” It’s another question to which the only answer was the book itself.

Mark Haskell Smith on his latest book, “Rude Talk in Athens,” about an obscure ancient Greek playwright and comedy as a form of revolution.

Carroll is author of the novel “Reel,” the story collection “Transitory” and the nonfiction work “Political Sign.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.