Why did we fail at COVID quarantines? Ask the L.A. writers who predicted it

On the Shelf

Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine

By Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley

MCD: 416 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“The Coming Quarantine” sounded like a good book title back when Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley sold their idea to publishers. The journalists even had a dramatic opening: a pandemic simulation, Manaugh says, “looking at what might happen if a disease takes hold of the U.S.”

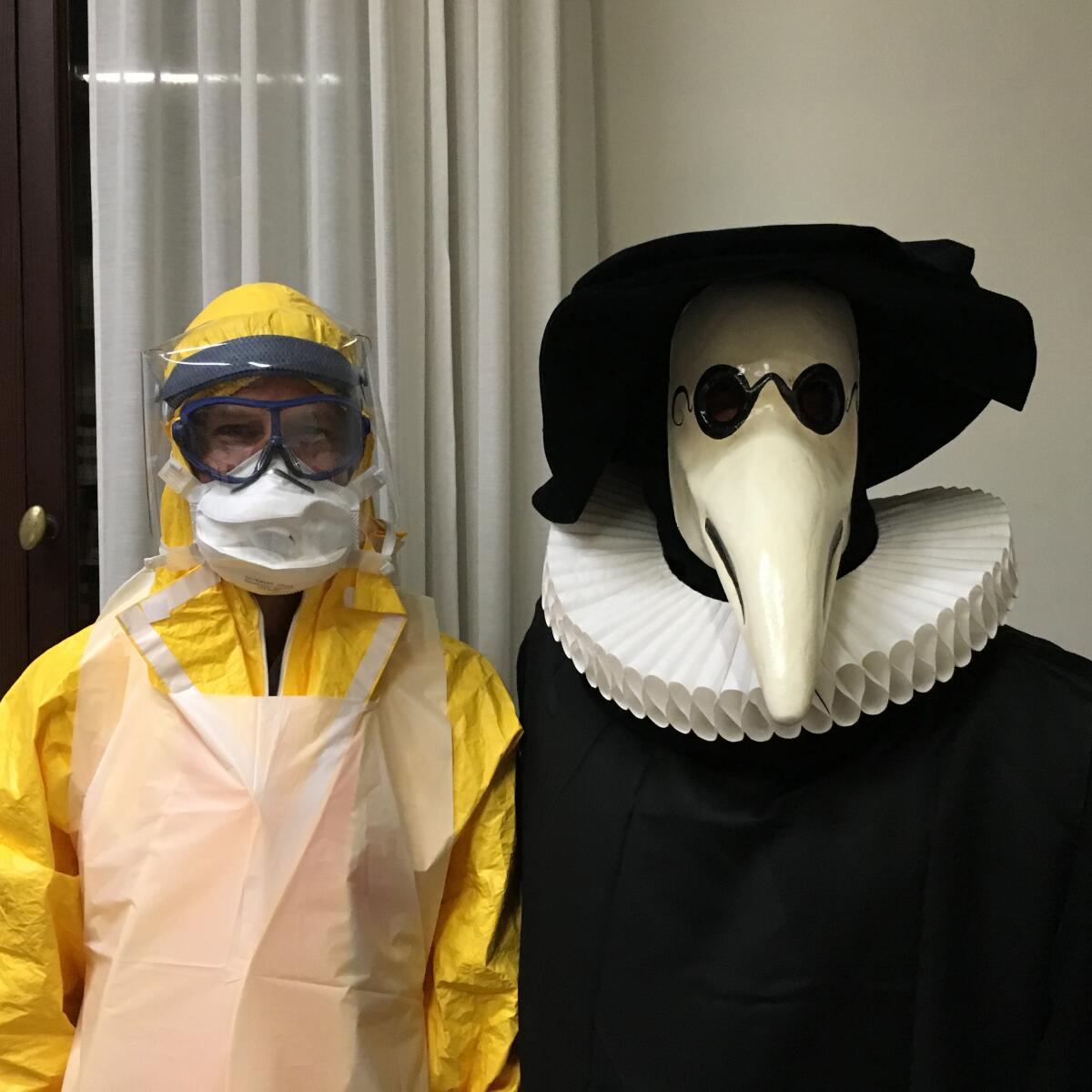

But, well, you know ... Their new book, retitled “Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine,” still explores quarantine through the centuries. But while their initial research involved a mission to find someone who had experienced a quarantine (they found a physician from Doctors Without Borders), the authors wrote the bulk of the book during the lockdown, with abundant evidence close to hand.

The history lessons in “Until Proven Safe” help illuminate where things went wrong in 2020 and what needs to change before the next lockdown, which they say is definitely coming. Last year’s “shelter in place” mandates were attempts at large-scale quarantine but, according to one expert they quote, if America had introduced stringent lockdowns as a broad-based quarantine early on, it could have saved many lives. “We just didn’t have the grit for it in the United States,” the expert tells them. “It’s quite humbling.”

The term “quarantine” experienced mission creep in 2020, used for everything from closed-off hospital wards to healthy people working from home. Manaugh and Twilley define it more classically as what happens when someone has been exposed to illness but is not yet confirmed to have it — as opposed to isolation, which comes for the already infected. “Typhoid Mary came up all the time but she was isolated, not quarantined,” Manaugh says. Twilley adds that there are a lot of similarities in how we should handle both during a pandemic.

Over the last three months, 17 writers provided diaries to the Times of their days in isolation, followed by weeks of protest. This is their story.

The couple, who spoke recently by video from Los Angeles, started thinking about the topic back in 2009 on a picnic in Australia, where they saw a spa and hotel repurposed from an old quarantine station. “Quarantines seemed like a practice from a different age, an obsolete technique,” says Manaugh. “But we quickly realized that was not the case. We chose that original title because we thought quarantine would become more common, not less common.”

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why were you sure there was going to be a need for a book about quarantine?

Manaugh: Humans are going into landscapes and encountering microbes and diseases they wouldn’t have previously encountered. They hop on a plane and bring them to Moscow or Los Angeles. We don’t have vaccines for those new diseases. Quarantine will be the one thing that will allow us to control these outbreaks.

Twilley: And it hadn’t been rethought since earlier eras. We wanted to be the people who warned this was coming. And then it came.

Who is the reader for this book?

Twilley: We hope it will reach a popular audience. The way quarantine has shaped the world was fascinating and now that we’ve all been through it, the book is interesting in a different way. But I also want people who make policy to read it so we can redesign quarantine better for next time.

You mention Hoffman and Swinburne Islands in New York, the sites of quarantine for immigrants arriving through Ellis Island. The setup successfully kept diseases out of the city but unfairly crammed people together in unsafe conditions. Have we learned to do better?

Twilley: We have not learned the lessons. The difficulty is really thinking about individual versus mass quarantine. People we spoke to had thought about how to reform quarantine for a few individuals, to make it safe and fair and give them legal rights. What hasn’t happened is thinking through how mass quarantine would work. We toured the new federal facility in Omaha before it opened and it hadn’t crossed their mind that the United States would need to quarantine more than 20 people.

Manaugh: As a society I don’t think we’ve learned to do it any better at all. The hope would be that COVID-19 lets us take a moment and think about quarantine and do it better the next time.

Jim Shepard has earned a cult following for refashioning history’s horrors. “Phase Six,” about a future pandemic, is his timeliest novel yet.

You write about how in the distant as well as recent past — Ebola in 2014 — people would panic and misinterpret facts and point fingers. Can we do better next time in this era of heightened division and mistrust?

Twilley: It’s astonishing to look at our research and then see contemporary examples play out the same way. There’s always a group that is stigmatized — and last year people started stigmatizing Asian Americans.

Manaugh: It depends on whether you’re a pessimist or an optimist. I think we’re going to see the same template over and over again. A lot of CDC planning was drawn out in great detail but we didn’t implement the plan. Parts of it were implemented successfully in places like South Korea.

Twilley: One expert told us the mistake he made before last year was not thinking through how politics would affect the implementation.

Manaugh: With the right political circumstances you can do quarantine, testing and tracing and isolation better. We just did not do it here. Ten years from now we’ll have another pandemic and we’ll see a lot of the same problems.

Is some distrust of the government justified?

Manaugh: A lot of things that happen in quarantine become permanent, so you run the risk of widespread implementation of facial recognition technology or biometric registration of civilians’ risk. There’s the dystopian risk of a government demanding quarantine.

Twilley: Trust is a big word in quarantine issues.

Manaugh: If we invest in quarantine the way we invest in earthquake, hurricane or tornado preparedness, it becomes normalized. You don’t think you’re in a dystopia if you see a tornado safe room at the airport. Communicating and having people believe you is essential. The problem is that public health gets presented as surveillance, but you need data points to understand if a disease is moving through society.

The journalist (“The Looming Tower”) and playwright (“My Trip to Al Qaeda”) discusses his frightening and eerily prescient novel, “The End of October.”

Would a president who cared and was competent have made a difference last year, or is it impossible to overcome a culture of American individualism?

Twilley: Things would have been better, but the simulations flagged those issues. There isn’t a strong civic culture anymore, and you can’t have public health without a public. People conflated liberty with the freedom to move around as they wished. We need to have a more sensible conversation about what we mean by freedom, but that’s a huge topic. And quarantine is very difficult to implement fairly in societies that are wildly unequal. So there are a lot of obstacles.

Manaugh: So many Americans give their genetic information to 23andMe but would never do that with the government. Right now, with the political culture in the United States, if a corporation stepped in with its own private quarantine plans, a large portion of the population would trust that before they trust the state.

That’s disheartening. Are we just doomed? Let’s start with the pessimist.

Manaugh: The optimistic answer is that if you tailor your quarantine plans for the specific cultural practices and different family sizes of each region, I think it can be successful.

Twilley: One researcher said if you present things as a choice, it’s much more acceptable. Quarantine will always be a little leaky and never will be perfect. But it doesn’t have to be perfect to work in terms of flattening the curve. It does have to get better. The point of our book is that people know how to make it better.

Faced with a rise in coronavirus cases, L.A. County will again require residents to mask up in indoor public spaces — regardless of vaccination status.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.