How teachers in L.A. and beyond turned away from Dr. Seuss

For nearly two decades, Read Across America, the nation’s largest celebration of literacy, was built around the work of one writer.

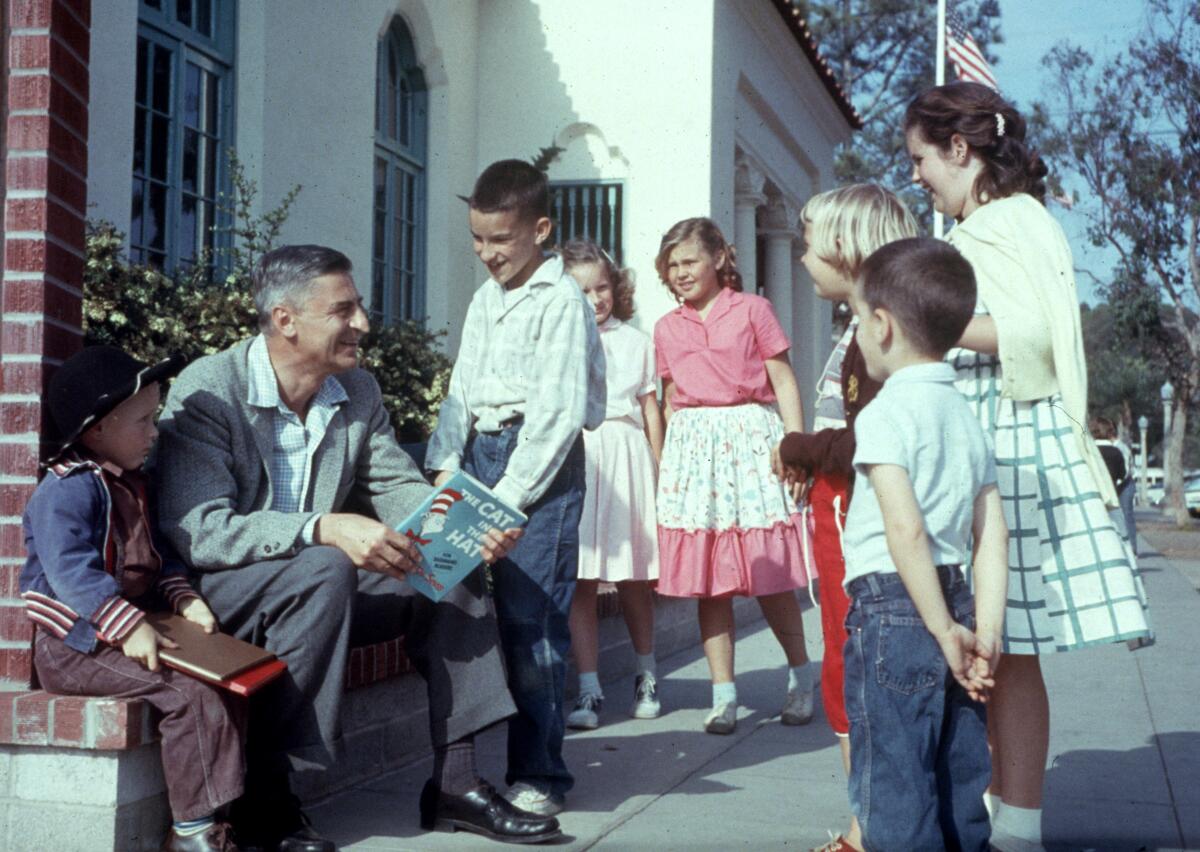

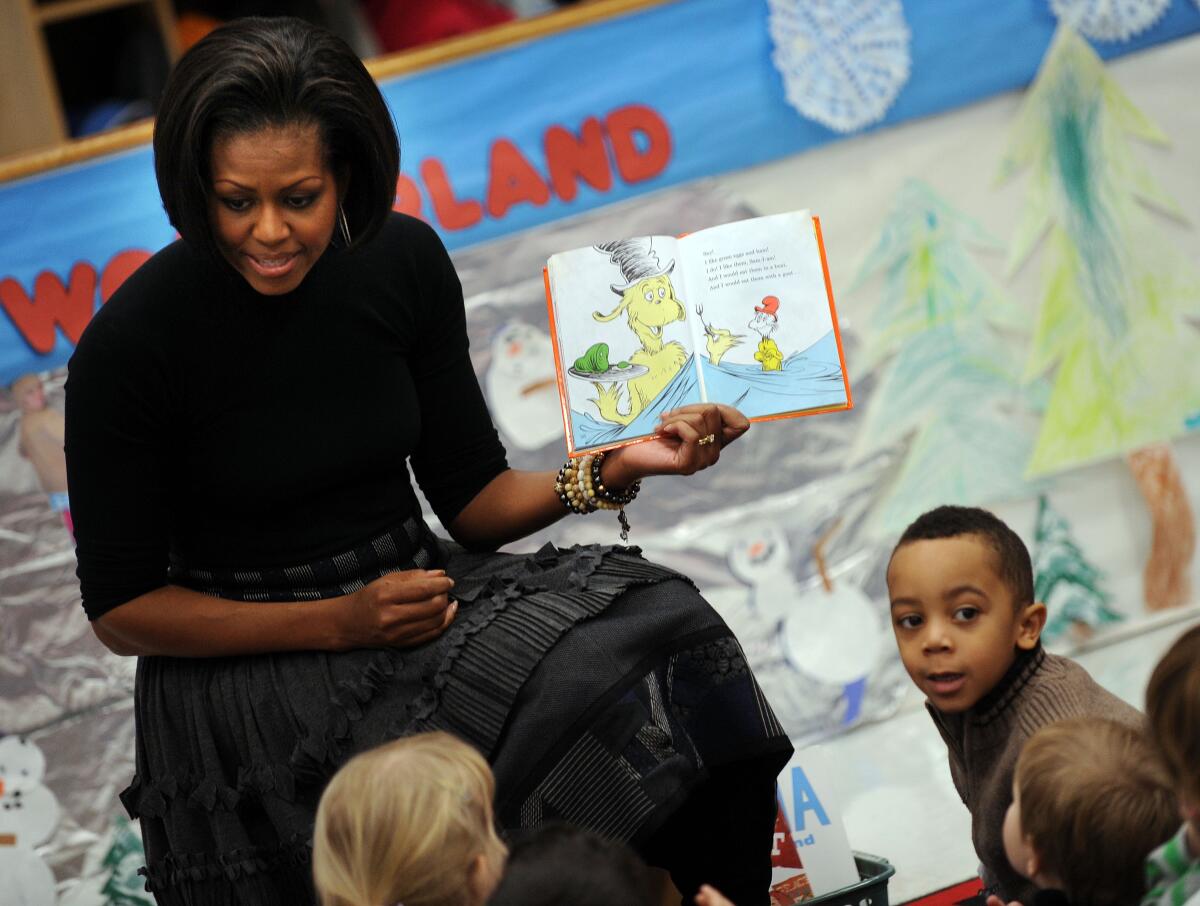

It’s no coincidence that the annual event, launched by the National Education Association in 1998, kicks off on March 2, the birthday of Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, who died in La Jolla in 1991. Typically, young readers join their teachers in weeklong festivities that include guest read-alouds and parties in which they dress up like the Lorax, Thing 1, Thing 2 and other beloved characters. In 2010, nearly 300 children gathered at the Library of Congress to hear First Lady Michelle Obama read “The Cat in the Hat.”

On many campuses, the tradition continues. But at some schools, including in L.A. County, educators have cut ties with the work of Geisel, opting instead to follow the NEA’s newer guidance and focus on “diversity and inclusion.”

Events surrounding this year’s celebration may have felt like a sudden, unforeseen shift in the program. President Joe Biden omitted any mention of Dr. Seuss from his Read Across America message; the author’s estate announced it would no longer publish six books deemed to contain offensive material; and reports circulated that Loudon County, Va., had banned his books. Some conservative rushed to declare that “cancel culture” had suddenly come for our green eggs and ham.

In fact, the Virginia county hadn’t banned his books but merely released guidance — back in 2019 — suggesting a pivot toward more diverse reading. Read Across America has been issuing the same guidance since 2018. And over the past several years, educators across the country have increasingly concluded that other books might better promote literacy and inclusiveness at the same time.

Why are many Americans committed to preserving words and images associated with forces bent on preventing fellow citizens from living freely and equally?

Letitia Avalos, who teaches kindergarten at Van Deene Avenue Elementary School in Torrance, came to that conclusion independently.

She first heard charges of racism in Dr. Seuss books last year. But because “things are sometimes taken out of context,” she decided to do her own research.

What Avalos found was unsettling: Especially early on in his career, before he wrote as Dr. Seuss, Geisel drew racist cartoons and ads portraying Black, Jewish, Indigenous, Asian, Mexican and Muslim people in stereotypical and demeaning ways. During World War II, he supported the internment of Japanese Americans. In “Waiting for the Signal From Home,” for instance, he depicted a mass of caricatured Japanese Americans lining up to pick up explosives, reinforcing the perception that they posed a threat to the country.

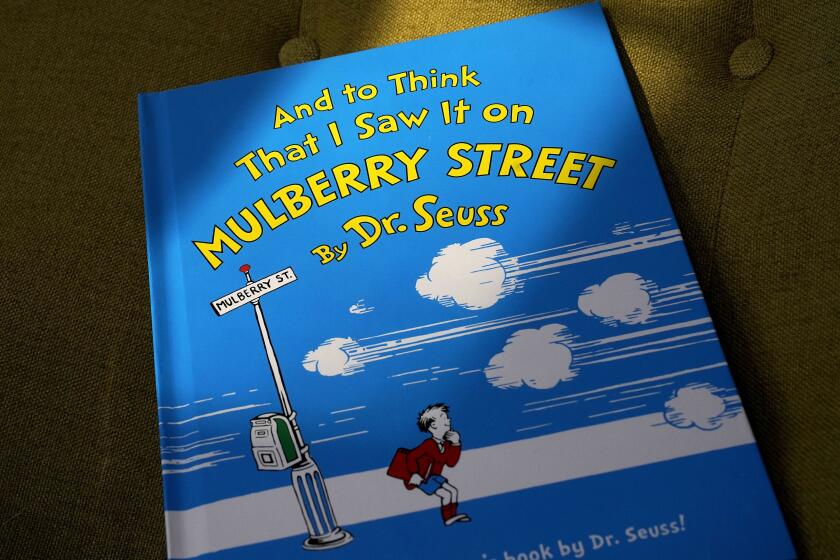

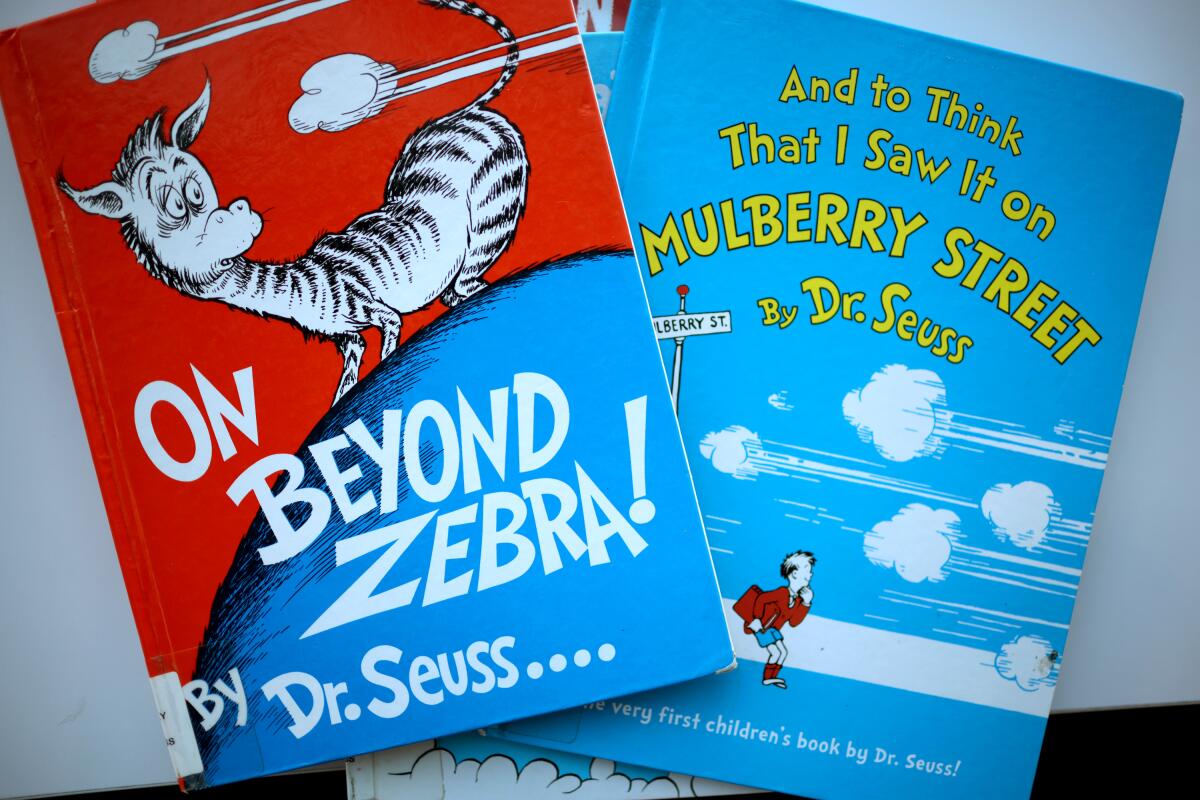

But it wasn’t just the cartoons, for which he later expressed some regret. As his estate, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, acknowledged earlier this week, offensive imagery sometimes seeped into his work for children. The company announced it would stop publishing six books — including “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” which launched his career as Dr. Seuss — that “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

A few years earlier, two researchers made an even broader point. Ramón Stephens, a Black PhD candidate at UC San Diego, teamed up with Katie Ishizuka, whose grandparents had been held in internment camps, to examine more than 2,200 characters in 50 of Geisel’s books.

Their study identified 45 “characters of color” across the works, 2% of the total. Among them, Ishizuka and Stephens found that 43 have “stereotypical East Asian characteristics” or turbans and two are identified as “African.” The researchers also note that all his characters of color are males presented in “subservient, exotified, or dehumanized roles.”

Ishizuka and Stephens also discuss Geisel’s “Horton Hears a Who!” Dr. Seuss Enterprises often bills the book as a text that promotes tolerance, and many have come to interpret it as an apology for the World War II propaganda. But Geisel “never issued an actual, explicit, or direct apology or recantation of his anti-Japanese propaganda,” write Ishizuka and Stephens.

In 2017, the researchers submitted their findings to the NEA, calling on the association to reconsider its focus on Dr. Seuss. By the time their study was published two years later, they had succeeded in their goal. In 2018, the NEA removed all of Geisel’s books from its Read Across America resource calendar, replacing them with diverse books and authors.

When asked what prompted the NEA to endits partnership with Dr. Seuss Enterprises, a spokesperson said: “We shifted to focus on celebrating a nation of diverse readers by featuring books in which all students can see themselves.”

During Read Across America Day, Second Gentleman Douglas Emhoff chose “I Dissent: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Makes Her Mark” for his official read-aloud, which was hosted by the Conscious Kid — a platform founded by Ishizuka and Stephens.

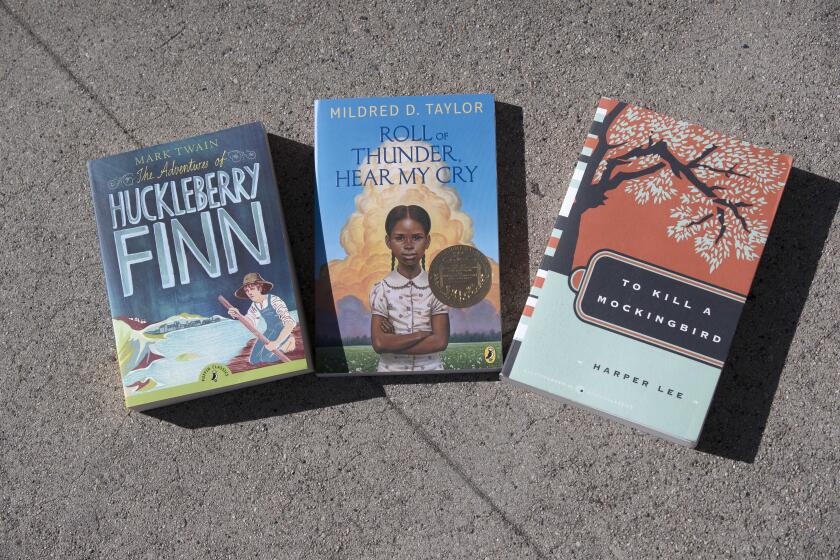

Some argue the books under review — including “To Kill a Mockingbird” and two YA classics — instigated racist incidents; defenders believe they’re antiracist.

In schools across L.A., educators were making similar choices. Avalos, the teacher in Torrance, said what she learned about Seuss last year was “a bummer.” But in her disappointment, she saw an opportunity.

“There are plenty of other books out there that can give us rhyming words or creative creatures and worlds, as he did,” she said. This week, Avalos’ Read Across America had traditional elements (albeit over Zoom this year), including guest readers and “crazy hat day.” But instead of Seuss titles, she and her “littles” enjoyed books like “Eyes That Kiss at the Corners,” a tale about a little girl of Chinese descent who redefines standards of beauty.

While reading the book to her students, Avalos noticed that some of them were giggling and pulling at their eyes. She used it as a teaching moment.

“We don’t do that,” she told them. “That could hurt someone’s feelings.” For her, learning to read involves learning respect and dignity as well.

At Micheltorena Street Elementary School in Silver Lake, principal Nichole Sakellarion said the national pivot away from Dr. Seuss informed her decision to do the same. But in her school, it didn’t constitute a radical change.

On her dual-language immersion campus, where students learn to read and write in both English and Spanish, inclusive reading is “our bread and butter of what we do every day,” Sakellarion said. “So it dovetailed right into what we were already doing.”

At Camino Nuevo Charter Academy’s campus in Harvard Heights, second grade teacher Kathia García celebrated Read Across America with Dr. Seuss every year — until 2021.

The daughter of Salvadoran immigrants, García grew up just a few blocks from the school, which mostly serves families with roots in Mexico and Central America. She still remembers chuckling as she read Dr. Seuss’ “Hop On Pop” as a 5-year-old. But she also remembers feeling uneasy when examining his books during coursework for her teaching credential.

Later, in conversations with her co-workers, she discussed the lack of diversity in his books, in which the few nonwhite characters “felt like caricatures of stereotypes.”

As part of her school’s planning committee, she helped change Read Across America at her campus.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

“After everything that happened last summer,” she said, referring to the protests against racism and police brutality, “we felt it would be wrong to have a whole week with activities centered around such a problematic person.”

Because the past year has been so difficult for students and educators, she and her colleagues decided to make compassion this year’s theme — “for ourselves, our community, our school, our families and for the world.”

Some of the changes to their Read Across America festivities are cosmetic. Instead of having students dress up as their favorite Dr. Seuss character, they were encouraged to take inspiration from any favorite book.

The real change was in this week’s read-aloud selections. Instead of “Green Eggs and Ham” and the like, students engaged with “The Reflection in Me,” which García describes as a text “about having positive conversations with yourself.” “The Mess That We Made” enabled students to grapple with the environmental crisis. And on Friday teachers read the Spanish translation of “Fourteen Cows for America,” a nonfiction book about a gift from the Maasai in Kenya to the U.S. following the Septe. 11 attacks.

“Growing up, I would read all of these books, like ‘Baby Sitters Club’ and Nancy Drew, and all of these were characters that I loved, but there weren’t very many that looked like me or sounded like me,” said García. “I want my students to be able to connect with the characters they read about. But I also want them to see how big the world is.”

Even if you think Dr. Seuss was a jerk, remember to separate the man from his work.

Does this mean Dr. Seuss will never see a classroom again? Is his reputation permanently tarnished? Philip Nel, a professor at Kansas State University, has written several books on Dr. Seuss, including “Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books.” But he believes the author’s legacy can be reexamined without being erased.

Nel backs Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ decision to stop publishing those six books and dismisses arguments that it amounts to censorship, because they will still be available in libraries.

The Dr. Seuss estate, which raked in $33 million in 2020, “is taking responsibility for what it is putting into the world and what it is profiting from,” he said. “In removing books that promote stereotypes, it has made a moral decision.” He maintains that Geisel did experience an evolution in his thinking, though not a complete transformation.

In its statement earlier this week, the company said its decision “is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families.” When asked for details regarding that plan, the company told The Times in an email that it “will continue to broaden its initiatives.” It has no plans to stop publishing or promoting any other books.

If the company really wants to make an impact, Nel said, it ought to consider using its platform to elevate other voices — just as Rick Riordan, author of the “Percy Jackson & the Olympians” series, has done with Black and LGBTQ authors.

Doing so, he added, would improve the company’s image. “I suspect they’ve come to realize that racism is not good for the brand,” Nel added. “And so, you could take a step further and align your brand with diverse books. There’s a capitalist incentive for you to do the right thing.” But there are bigger issues at hand, he said. Children’s books are seldom taken seriously, “but they are, in fact, the most important. These are the books we use to first figure out who we are, what we believe, who matters.”

The author of ‘How to Be An Antiracist’ has a timely new spinoff board book, ‘Antiracist Baby,’ out soon.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.