Appreciation: Why working with Larry Flynt was an endless adrenaline rush — and an education

I was Larry Flynt’s book publicist and personal publicist for 15 years — from 1996, three months before the movie “The People vs. Larry Flynt” was released, until 2011. I watched him be mesmerized by Terry Gross during their “Fresh Air” interview and get slaughtered by Bill O’Reilly on Fox News. He did all the shows — Bill Maher to Larry King, CNN again and again, and I’d play poker with him to pass the time in every green room in town.

Working for Mr. Flynt, as I always called him, taught me more about the personalities, secrets, limitations and roadblocks of the media than all my other clients combined. Meeting with him a few times a week at his office on Wilshire Boulevard or at the Four Seasons was an endless adrenaline rush. What might he say, to whom might he say it, what would I need to do about the fallout?

A businessman first, his primary concern was making money. He’d have a briefing each morning about the stock market and he’d check the numbers throughout the day, but as carefully as he monitored the fluctuations on Wall Street, he also compulsively watched CNN, MSNBC and Fox News — often simultaneously. Next to making money, politics was all that mattered. He was a major contributor to the ACLU.

The foreign press adored him. And American journalists and celebrities, no matter how they might have bashed him in public, would fall over themselves to get a handshake on seeing him at a restaurant or in a private meeting. He was glamorous, like a mysterious, charismatic character from a novel — he loved the spotlight, he told the truth and he was fearless.

He had his faults and his detractors, but my recollections of Mr. Flynt, who died Wednesday at age 78, are here for whoever wants to read them. As he would say, no one is forcing you to read this. It’s a free country. Or at least that’s the goal, and Larry Flynt spent the second half of his life trying to keep it that way.

He hired me to promote his first book, “An Unseemly Man: My Life as Pornographer, Pundit, and Social Outcast,” in 1996. “What are you wearing to the interview?” my mother asked me. I fell over laughing, but this is what everyone wanted to know.

Larry Flynt, the founder of Hustler magazine, repackaged himself again and again — an unlikely 1st Amendment champion, a self-appointed arbitrator of political hypocrisy and a born-again Christian.

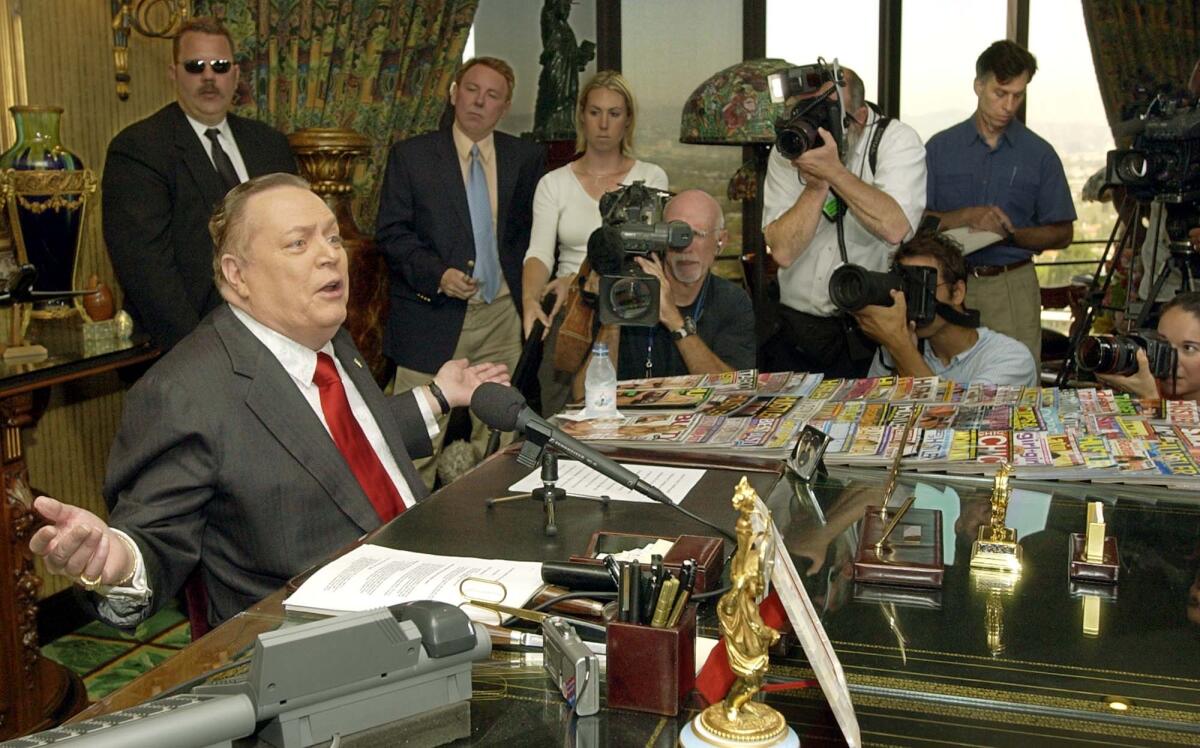

His office was the size of a football field. Several plush couches and chairs, vases, floor-to-ceiling paintings and his massive desk made from … was it Italian marble? It was all so intimidating. And there he was — sitting in his gold-plated wheelchair behind that desk, wearing a bright green sweater, puffing on his cigar, a swirl of smoke rising above the solid gold #1 pendant blinding me from across the room. (I wore a tailored suit and low heels.)

We had spoken on the phone several times already, and the interview was brief, my answers rote. I did the best I could. And then he said, “This interview doesn’t really matter. I’ve already decided to hire you because you’re so good on the phone and I figure most of the work you do is over the phone, so you’ve already passed the test.” He was, of course, right. Not that I’m so good on the phone, but that’s how we did all our work back then, before email and texting. Flynt made his decisions from instinct and playing the odds, and that was the first lesson I learned from him — trust your gut.

Watching him expose hypocritical politicians like Reps. Bob Barr and Bob Livingston — the House Speaker-designate who stepped down amid Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial after admitting an extramarital affair — was fascinating. Observing firsthand how the media would blatantly censor Mr. Flynt — rewrite his words, cut a swath of his interview out of the tape to shift the context — was another eye-opener.

Hearing him speak so bluntly to reporters was always hilarious yet could be stressful. What might he say? We’d be at lunch and someone from Vanity Fair or Newsweek might call: “What can you tell me about the Livingston case? “He was the third in line,” Flynt would rattle off, referencing the order of presidential succession, “and everything that he was accusing Clinton of he was doing himself. He had three mistresses. He made Clinton look like Mary Poppins.” And that was it. The reporter wanted that precious sound bite, and Flynt was delighted to deliver it.

When we held a news conference about Livingston, more than 200 reporters showed up, landing their helicopters on Mr. Flynt’s Wilshire rooftop, standing crushed together in his office, their cables running up and down the hallways. Livingston had called Mr. Flynt a “bottom feeder,” and when asked about it, my client’s face broke into one of his classic slow smiles as, in his much-imitated gravelly voice, he unloaded one of his favorite and oft-repeated lines: “Yeah, that’s right, but look what I found when I got down there.”

He got a huge laugh.

“I disagreed with Falwell,” Flynt said, who died on Wednesday, “on absolutely everything he preached, and he looked at me as symbolic of all the social ills.”

Larry Flynt was always a gentleman to me and to the people I brought to interview him. He was gracious. He was on a mission to keep politics and our politicians honest, and he despised hypocrisy, especially in government. He wasn’t afraid to dig to find the truth, to accuse, because he already knew that staying alive for so long after a near-fatal gunshot — a wheelchair user for more than 40 years — was a miracle, but also a certain kind of death in and of itself. I never heard him complain. I believe he wanted to make a difference. As Thomas Friedman wrote in his review of “The People vs. Larry Flynt,” “Larry Flynt is a true American hero.”

I had stopped being his publicist several years before Trump’s election. But when Trump won, I called Mr. Flynt and asked if he wanted to go to lunch — “I need you,” I told him, “to tell me why we shouldn’t be worried.” Lunch to him was breakfast. Over his eggs, juice and coffee, he put his hand on my arm, as he always did when about to make a pronouncement: “Ke-em,” he said, “don’t worry. Trump is just crazy. It’ll all fizzle out.”

Dower is a literary publicist and poet; her latest collection is “Sunbathing on Tyrone Power’s Grave.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.