Crime novelists dish on writing about cops in a moment of reckoning

For Rachel Howzell Hall, the titular female character in her Detective Elouise Norton novels is the epitome of a good cop.

In Hall’s crime fiction series, the down-to-earth Norton is a Los Angeles Police Department homicide detective who uncovers mysteries in Los Angeles while battling her own struggles. As a Black woman living and working in a city, “she knows what it is to be on the other side of the badge, and she didn’t like it, but yet here she is,” said Hall. Her approach instead is community policing.

“I think for the most part, people of color, writers of color who write mystery and crime, have written the proper cop,” Hall said Friday evening during a Los Angeles Times Festival of Books event. “There are those cops that don’t do the right thing and we reflect that in our novels because we’ve lived it.”

Hall’s latest novel, “And Now She’s Gone,” published last month, is a story about secrets, violence and fear featuring two women on a dangerous pursuit of cat-and-mouse.

Rachel Howzell Hall’s new novel, “And Now She’s Gone,” breaks the crime-fiction mold; its success proves a long line of publishers wrong.

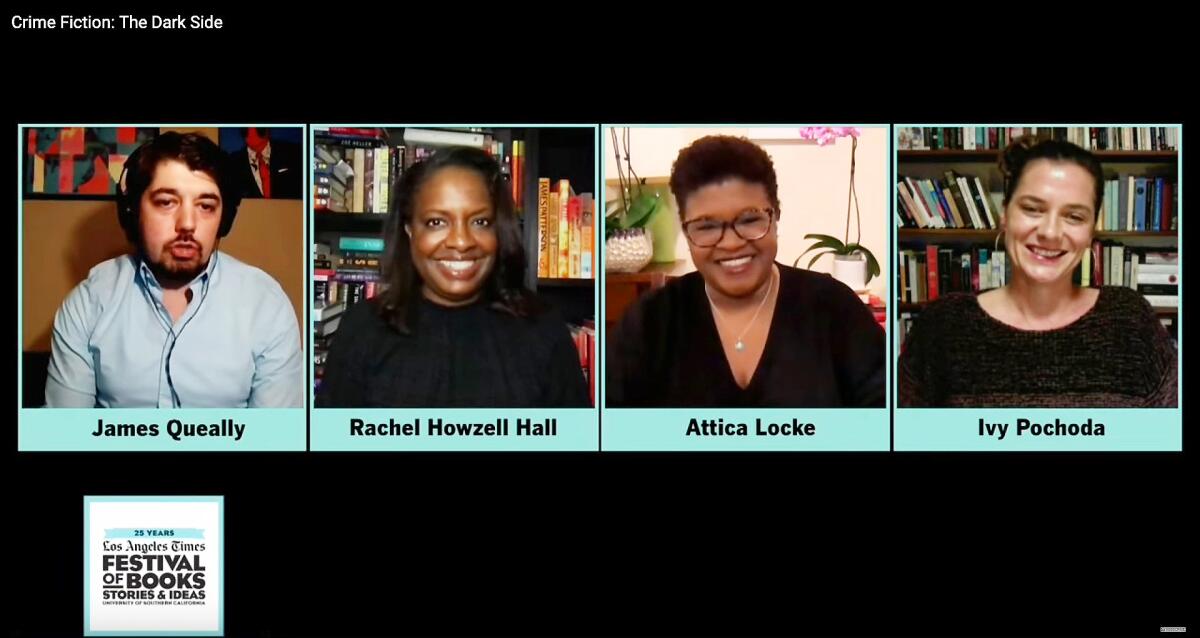

Hall’s response came from a question by Times crime reporter James Queally, author of the novel “Line of Sight,” who asked the panelists how they’re writing about law enforcement during a national reckoning with police brutality.

Hall and Queally were joined by other L.A.-based crime fiction writers Attica Locke and Ivy Pochoda for a wide-ranging conversation about character voice, avoiding tropes, what they’re reading, the writing process — before and during a pandemic — and more.

For Locke, the answer to Queally’s question was simple: “This isn’t on us to fix. Yes, it matters what we’re putting in these books, but I want all of that attention to be focused on the police and the people who can actually enact real change. I feel like it’s a little navel gazing to suggest that what we’re putting in these books can really shift what’s happening to real people at the hands of police.”

Locke, whose latest novel, “Heaven, My Home” was released last year, said that she never wanted to write about police; it’s an establishment she didn’t understand and a perspective she didn’t share. But when the idea spawned to write a series about murders in small Texas towns, she thought of Texas Rangers.

“[They] were the most interesting law enforcement agency” to bring readers into the story, she said.

Attica Locke’s ‘Heaven, My Home’ follows a conflicted Texas ranger from ‘Bluebird, Bluebird.’

“Heaven, My Home,” the second part in Locke’s Highway 59 series, tells the story of a Black Texas Ranger grappling with loyalties when he investigates the disappearance of a white supremacist’s son.

Pochoda also said she swore she’d never write a cop. “When I decided that I was going to include a detective in my novel I realized that I couldn’t come up with a better manifestation of what it’s like to be a woman in a job where you’re not believed.

“… So when I realized that I can have a female cop who is trying to do good but is always being second-guessed as the person who ties my story together, I thought, ‘I damn well better put a cop in the story because it’s a perfect way to articulate this anger that I have about our place in society,” she said.

Pochoda’s latest novel, “These Women,” which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist this year, is a story of loss, power and hope told through the lens of five very different women who are united by one man and his lethal obsession.

Before the end of the hour-long talk, Queally asked the authors about their writing process: “Music or no music? Caffeine? Booze? Tea? What’s your ideal writing situation and circumstance?”

For Hall, it’s having coffee and a routine: She wakes up at 5 a.m. every day and writes until 7 a.m. But working from home because of the pandemic has stripped her of an important step in her writing process: commuting.

Pochoda walks through the setting for her new noir, “These Women,” and talks about centering the victims and past collaborations with Kobe Bryant.

“To work, from work, to my daughter’s soccer practice, I spent that liminal space, that time, thinking about what I’m supposed to be writing when I get to that end point, and I don’t have it anymore,” Hall said.

An empty house is the ideal writing environment for Locke and Pochoda.

“I like to write in the house alone because it’s energetically different when people are in it,” said Locke, “and people that you care about are in it.” Windows and music are also important. “I create a playlist for every book, every project.”

Pochoda, who lives with her daughter and husband, said she’s struggled with the notion of applying to a writing residency.

“The truth of the matter is, it seems ridiculous to have to do that when I can do that at home if everyone just got the hell out of the house,” she said, laughing. “I can have my own writing residency right here.

“The problem is they don’t comply.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.