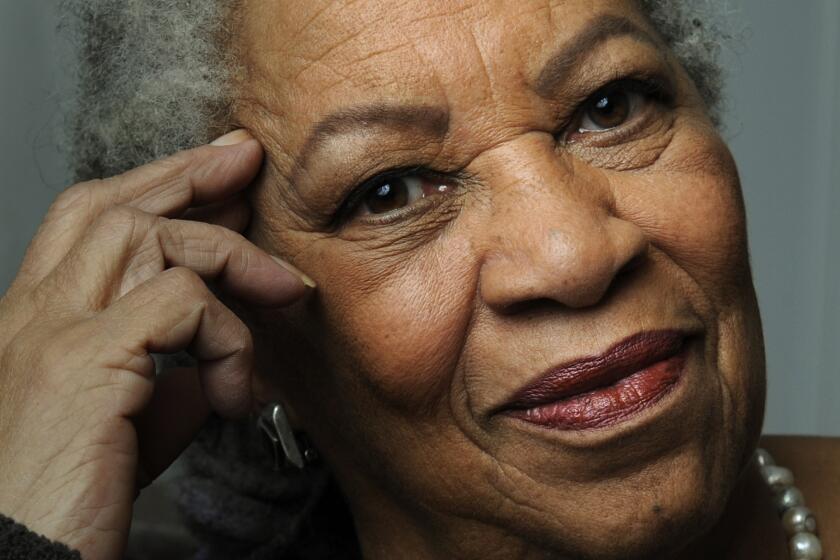

Why an L.A.-area school district banned, then quietly reinstated Toni Morrison’s ‘The Bluest Eye’

On Sunday, free speech organization PEN America sent a California school district a letter.

“We write to encourage the Colton Joint Unified Board of Education to reverse its recent decision to remove the renowned ‘The Bluest Eye’ by Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Toni Morrison from its core and extended reading list for upper-level AP English Literature classes,” the letter stated.

“The decision to remove this book is educationally and constitutionally unsound. We urge you to reinstate the book as soon as possible.”

Within an hour, the president of the board of the district, in San Bernardino County, responded that “The Bluest Eye” was, in fact, no longer banned. After being removed from the reading list in February to some public consternation, it had been quietly reinstated during an August board meeting.

“In preparing for this decision, our approach was to personally reach out directly to those who are most impacted by it, our teachers and families,” school board spokeswoman Katie Orloff wrote The Times in an email. “For us this issue also involved improving our processes and procedures for book selection ... as well as the process for parents opting their students out and expanding their representation in the book selection committee.”

PEN quickly reversed its own plan to publish the open letter, which was set for Monday to mark the beginning of Banned Books Week.

The organization recognizes the issue each year with a variety of programming, including book drives, readings, appearances, petitions and events.

Morrison’s 1970 novel frequently draws controversy for its content, including rape and incest, and has been banned in states including Colorado and North Carolina — despite being part of the body of work that earned the author the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The American Library Assn. tracked 377 challenges to library, school and university materials and services in 2019. Of the 566 books that were challenged or banned, these are the “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2019.”

Back in February, four out of seven Colton school board members voted to remove “The Bluest Eye” from the district’s reading list. Two members opposed the motion and one member abstained.

The San Bernardino Sun reported Morrison’s novel was the only book removed from a district list of almost 500 works of literature. District officials at the time could not remember another instance of such a removal, according to the Sun.

Parents, teachers and students throughout the district deluged the board with emails and comments both opposing and advocating for the book.

On Aug. 20, the Colton school board held a regular (albeit virtual) meeting that was quickly overtaken by the book debate. Members listened to almost an hour’s worth of public comments and eventually voted to reinstate “The Bluest Eye,” six months after its removal. Three board members reversed their votes from February: President Patt Haro, Frank Ibarra and Israel Fuentes. Five members voted to put the book back on the reading list. Two opposed the motion.

At the Colton Joint Unified School District board meeting on Aug. 20, the school board voted to reinstate “The Bluest Eye” onto the reading list.

“A decision to remove a book, particularly a Toni Morrison book, one of the prominent Black authors in American literature — regardless of the individual motivation of those parents, which I think was valid — the message that that decision sends to the Black community within our school district was one that I just couldn’t support,” Colton School Board Vice President Dan Flores told The Times.

Although the change caught PEN by surprise, Flores clarified that the board hadn’t intended to keep the reversal under wraps. In fact, both the meeting minutes and a video of the meeting (recorded over Zoom because of the COVID-19 pandemic) are publicly available online. Local reporters who had written about the original ban simply hadn’t covered its reversal.

“We’re very pleased that the school board reversed their decision,” James Tager, PEN’s deputy director of free expression research and policy, told The Times. “It shows that it’s never too late to reverse a book ban, [and] it’s never too late to reverse a bad decision.

“And it’s a demonstration that these concerns are taken seriously and that there is utility to raising your voice. I hope it sends a message to convince parents, teachers, librarians across the country that there’s a point and a purpose to expressing opposition to book bans anywhere they happen.”

On the August Zoom call, some community members suggested that teachers had asked the local press to cover the removal.

“To call the media so you could all drag these people through the [mud] to prove your point and be the loud voice — does that make your opinions correct?” parent Nicole Littlefield asked in August. “Need I remind you who puts you in those seats you hold?”

Others argued the ban should stay. “I could not continue to read this book, as its contents overwhelmed me and compromised my morals and beliefs,” former student Alexis Nicols said at the meeting. “I have always been taught that when participating in something, always keep in mind: if your mom, dad or God was standing next to you, would you continue to participate in that activity?”

Maybe they should call it Toni Morrison week.

“The Bluest Eye” tells the story of Pecola Breedlove, an 11-year-old Black girl in Ohio who prays every day for the blond hair and blue eyes that she believes will make her beautiful.

“Being a minority in both caste and class, we moved about anyway on the hem of life, struggling to consolidate our weaknesses and hang on,” Morrison, who died in in 2019, wrote in the novel. “Or to creep singly up into the major folds of the garment.”

Pecola is raped and impregnated by her father, developments that have sparked controversy before. The novel made the American Library Assn.’s “Top 10 Most Challenged Books” list in 2006, 2013 and 2014; on Monday the association announced “The Bluest Eye” was on its combined list for the past decade.

The Colton district’s initial removal of the novel had deprived students of an important teaching tool and raised constitutional concerns, effectively resulting in censorship, Tager said: “We’ve seen other examples around the country where Morrison’s books have been singled out for banning in ways that raised the obvious inference that it was selected, in part, because it grapples with the uncomfortable realities of race and racism in America.”

In particular, PEN’s letter cites the 1982 case of Board of Education vs. Pico, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment limits the discretion of school boards to remove books from middle and high school libraries.

“This is a theme that has been consistent throughout decades when it comes to book banning in the United States,” Tager said. “It’s ingrained in one of the most important court decisions, and yet the problem remains: Books written by or featuring people of color are disproportionately likely to be challenged or banned.”

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

Books by and about people of color offer Black students — who make up 6% of the Colton district — representation, as one student attested at the August meeting.

“Being an African American girl transitioning into adulthood, I formed a special connection with this book,” Grand Terrace High School senior Destany Lewis said. “This was the first time I had read a book at school following a main character that looked like me.”

Colton’s African American Parent Advisory Committee also advocated for the reversal of the “Bluest Eye” ban.

“We continue to tell our Black community that they matter, but our actions show otherwise,” AAPAC commented at the August meeting. “How can we support a marginalized community and build trusting relationships with them when actions represented from the school board go against the words of support echoed for the African American community?”

Lewis said that only 13 out of 300 books, or roughly 4%, on Colton’s approved list for English classes are written by Black authors.

The reversal coincided with an ongoing movement for civil rights ignited by the police killing of George Floyd in May. Activists have subsequently pushed for more African American history taught in schools — and President Trump has pushed back.

“In the political environment that we’re in right now and the emphasis on Black Lives Matter and the Black community, it definitely elevates that conversation, brings it to the forefront,” Flores said.

“Unless we’re lifting everybody up and providing an opportunity and voice and space [and] representation for everyone, then we’re not really doing a great service to our students,” he added.

With “Beloved” and other writings, Toni Morrison gave voice to the silences in the past and created some of the most memorable characters in American literature.

The PEN letter cited an “obvious alternative” to censorship: an “opt out” process that gives any parent the right to object to a book on Colton’s reading list and to select an alternative.

“There is no educational or constitutional justification for allowing members of the community to dictate reading lists for students who are not their own children,” read the letter.

Opting out allows parents to choose which books their children read without forcing those choices on others, Tager said. Otherwise, “You are taking the option away from other parents who would want their kids to read those books.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.